By Jane Beitler

Circling Earth, a landmark Earth observing mission turns a now-dark eye over the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Soon, engineers will nudge it out of orbit, to burn up in Earth's lower atmosphere. NASA's Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) was already several years beyond its life expectancy when it made its last scans of Earth's surface in October 2009. But scientists have not yet unlocked all the secrets of ICESat data, captured during this time of rapid changes in the cryosphere. They continue to pore over ICESat data to learn more about these unprecedented events and, possibly, what the future may hold for Earth's frozen regions.

Thick and thin

ICESat was launched to sense ice, clouds, and land, as its name suggests—but its most compelling observations were of snow and ice. Just a few degrees of temperature change in the sensitive polar regions have begun to alter cryospheric processes that were stable for thousands of years: glaciers recede; ancient, massive ice sheets and ice shelves exhibit rapid summer melt and lose mass; once-thick sea ice cover succumbs to summer warmth, becoming thin and rotten.

These changes raise many essential questions. How much icy mass is being lost? How might global sea levels be altered as ice moves from land to ocean? While other satellite instruments have for decades measured the extent or outlines of glaciers, ice sheets, and sea ice, they lacked the third dimension for mass estimates: thickness. The Geoscience Laser Altimeter System (GLAS) instrument on board ICESat used lidar to measure surface elevation, data that can then be used to calculate thickness and total mass, and over time to observe volume change.

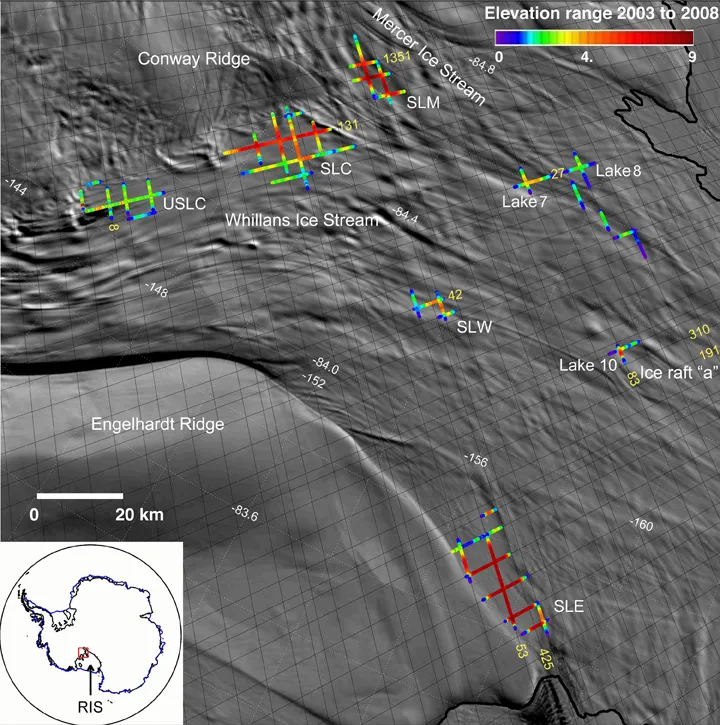

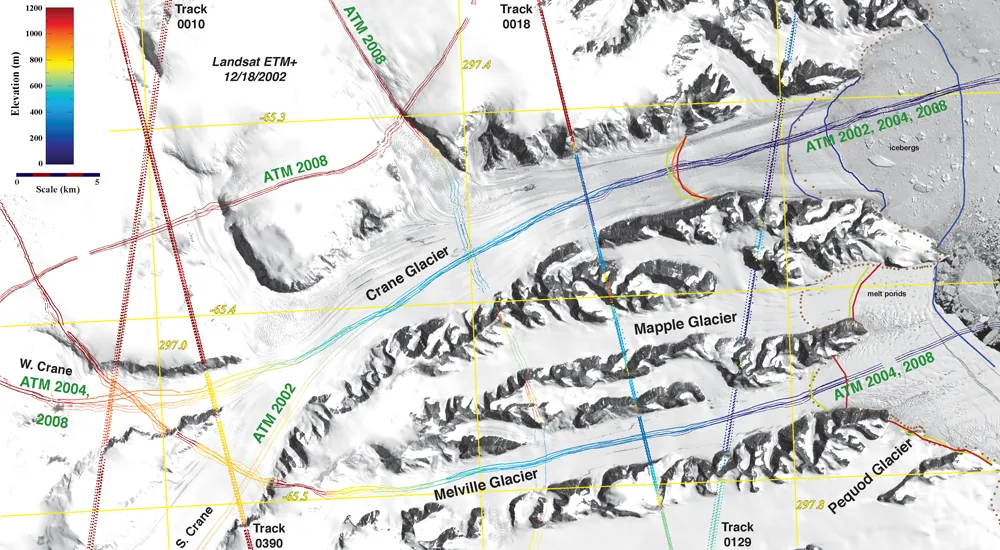

Beginning in 2003, scientists could study and monitor the wasting of Greenland's ice sheet, or of Antarctic Peninsula ice shelves and glaciers, in three dimensions. ICESat data continue to answer questions and stimulate new research: do ice shelves help hold back glaciers? Is melt water lubricating the base of Greenland's ice sheet? Is the older, thicker Arctic sea ice that is the mainstay of the ice cover disappearing? GLAS data have also helped uncover surprising features and dynamics, such as a series of lakes thousands of feet beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet, flowing from basin to basin and draining the water at the base of the ice streams.

An active archive

ICESat/GLAS offered the first chance for a year-round look at snow and ice elevations in these remote lands that are dark and dangerous and severely cold during long winters, forbidding on site research. To seize the opportunity for as long as possible, the GLAS science team devised measurement campaigns to make best use of three onboard lasers and to stretch their lifespans.

These 33-day campaigns covered each year's most crucial times and events, such as maximum ice and snow extent in late winter, the beginning of melt season in spring, and the end of melt season and sea ice minimum in October. Originally planned for a three-year lifespan, the GLAS instrument collected almost seven years of data. Scientists and data managers expect ICESat’s record to be of vital scientific importance for decades to come, and an irreplaceable record of climate during a period of rapid change.

Working with the GLAS science team, NSIDC continues its data management mission by maintaining the GLAS data archive and continually serving data and information to researchers. The science team recently improved its data algorithms, improving data quality, and is reprocessing the entire time series of data. Before the end of 2010, a new version of data, Release 33, will be archived at NSIDC and will be available to scientists and researchers. Meanwhile, NASA is preparing for a new ICESat II laser altimeter, scheduled for launch in 2015. In the interim, NASA’s Operation IceBridge mission, initiated in 2009, is collecting airborne remote sensing measurements of coastal Greenland, coastal Antarctica, the Antarctic Peninsula, interior Antarctica, the southeast Alaskan glaciers, and Antarctic and Arctic sea ice. These data are also accessible through NSIDC.

For more information on ICESat, see ICESat Data at NSIDC.

For more information on IceBridge, see IceBridge Data at NSIDC.