What is the Cryosphere?

Overview

What is the cryosphere?

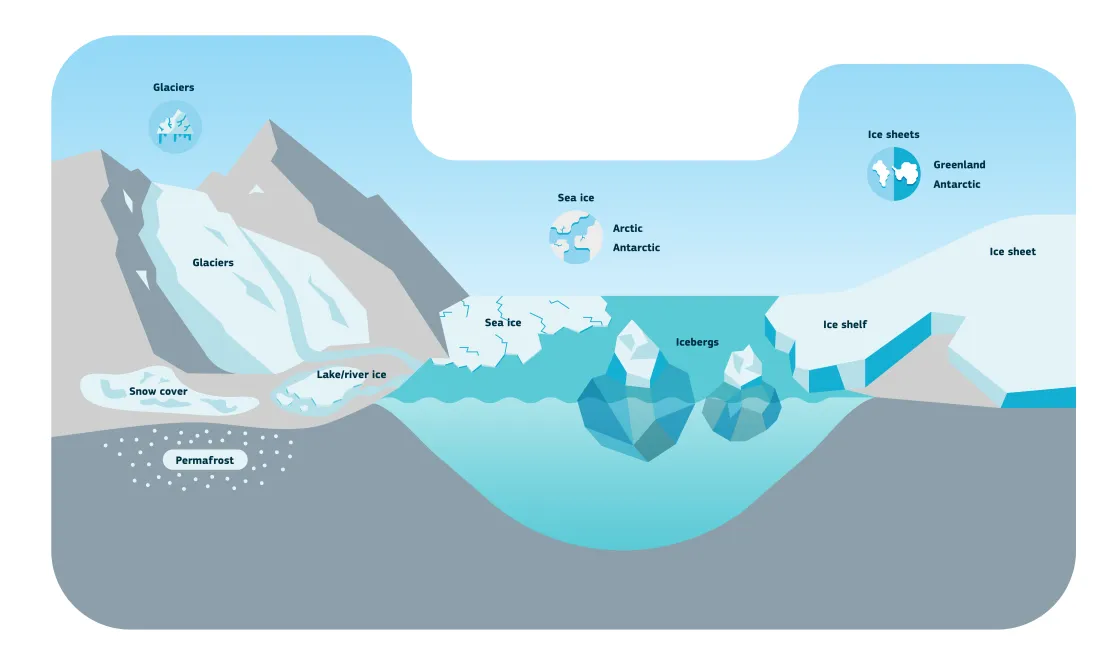

The cryosphere refers to Earth’s ice in all its forms. The term comes from the Greek word for icy cold—krios. The cryosphere includes:

- Snow on the ground

- Lake and river ice

- Frozen ground and permafrost

- The Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheets, ice caps, and glaciers

- Ice shelves and icebergs

- Sea ice

A few basic facts about ice:

- Ice mostly forms at the mid- and high latitudes, at high elevations, or at night when temperatures are below freezing.

- Ice is less dense than liquid water, allowing it to float in oceans, lakes, and rivers. As global temperatures increase, many of these water bodies may lose their ice cover.

- Ice provides water for people, animals, and plants.

- Where snow has accumulated for hundreds, even thousands, of years, it compresses into glacial ice. Scientists can drill into this ice and recover cores to retrieve information about Earth’s past climates. The Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets, both of them huge masses of glacial ice, have existed for thousands or even millions of years.

- In the Arctic and Antarctic, sea ice grows in fall and winter, and melts in spring and summer.

Snow

Snow is precipitation made up of ice crystals. When low temperatures and high humidity levels combine in the atmosphere, ice crystals grow—typically in clouds. These tiny crystals often stick together. When the crystals get heavy enough, they fall as snowflakes. Snow falling through the atmosphere is not considered part of the cryosphere; it becomes part of the cryosphere when it lands on the surface.

- Snow is mostly a feature of the mid- and high latitudes, and of mountainous areas; snow can even be found near the equator at high elevations.

- Snow’s bright white color reflects sunlight, cooling the planet, and affecting climate.

- Snow provides an insulating layer during winter, under which plants and animals can survive the coldest months.

- Snowmelt provides water for agriculture, people, plants, and animals.

- Where it is cold enough for year-to-year snow accumulation, a glacier may form.

Frozen ground & permafrost

When water turns into ice in soil, it becomes frozen ground. Permafrost is ground that has been below 0 °C (32 °F) for at least two years. It consists of soil, gravel, and sand, usually bound together by ice. If the ground freezes seasonally, thawing at least once within a two-year period, it is not considered permafrost. Instead, it is simply called frozen ground.

- More than half of all the land in the Northern Hemisphere freezes and thaws every year. Frozen ground can be found in high elevations, as well as parts of the Arctic and Antarctic.

- Permafrost can be found on land, as well as below parts of the ocean floor. In the Arctic, some parts of today’s ocean floor were dry ground during past ice ages when global sea level was much lower.

- Permafrost is generally found where the annual average temperature is below freezing. In the Arctic, regions like Greenland, the US state of Alaska, Russia, China, and Eastern Europe contain permafrost. Permafrost is also found in high mountain areas and the Tibetan Plateau.

- Permafrost has an active layer near the surface that thaws and freezes annually.

- Many roads, buildings, dams, or other structures have been built on top of permafrost. As the Earth warms, permafrost thaws, causing the ground to deform—sometimes causing considerable damage to these structures.

Alpine glaciers

Alpine glaciers are frozen rivers of ice, pulled by gravity, slowly flowing under their own weight down mountainsides and into valleys. Glaciers form when snow compresses over many years into thick ice masses.

- The mass loss from thawing glaciers are major contributors to sea level rise.

- Glaciers carve landscapes by eroding mountain valleys and shaping underlying sediments as they flow.

- Some glaciers flow into the ocean, known as marine-terminating glaciers. They discharge icebergs in a process known as calving.

Ice sheets

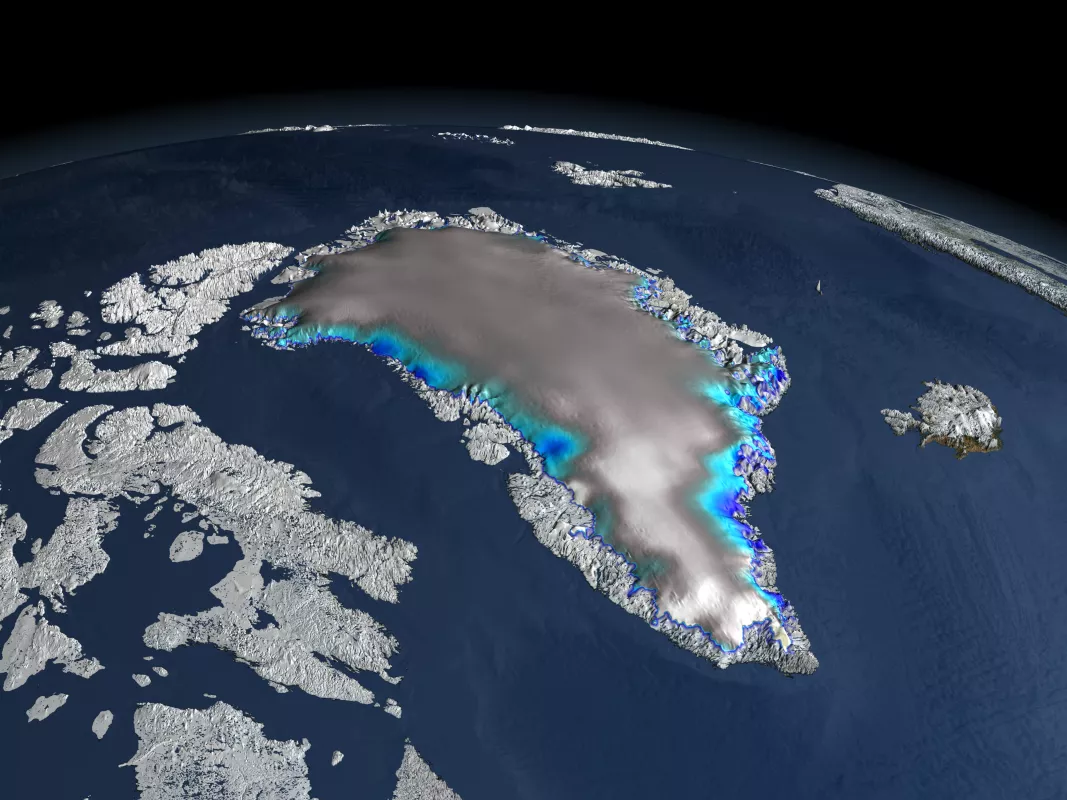

An ice sheet is defined a mass of glacial land that extends more than 50,000 square kilometers (19,300 square miles) across a land. Ice sheets spread out in broad domes and alpine glaciers may flow from them.

- There are only two ice sheets on Earth today, the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets. During the last ice age, which ended 11,700 years ago, ice sheets also covered much of North America and Scandinavia. During the peak of the last ice age, glaciers and ice sheets covered about 32 percent of Earth’s total land area.

- Ice sheets contain enormous quantities of frozen water. Together, glaciers, ice caps, icefields, and the Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheets contain more than 70 percent of the freshwater ice on Earth. Most of that freshwater is stored in the ice sheets.

- At its thickest, the Greenland Ice Sheet is over 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) thick, or roughly 3,200 meters (10,500 feet). The Antarctic Ice Sheet measures nearly 4.9 kilometers (3 miles), or 4,900 meters (16,100 feet), at its thickest point on the Astrolabe Subglacial Basin.

- On average, the ice on both the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets, which has accumulated over millions of years, is more than 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) thick. The colossal weight of both ice sheets has pushed down the land under them.

- Mass balance is a term used to characterize the mass gain or loss of an ice sheet. (This measurement is also applied to ice caps and icefields.) Ice sheets grow if the amount of snow falling on them exceeds the melt runoff, evaporation, and discharge of icebergs into the ocean. However, ice sheets lose mass if melt, evaporation, and iceberg discharge exceed the snowfall input. Both ice sheets are currently losing ice and contributing to sea level rise.

- Data from 2020 show that if the entire Greenland Ice Sheet melted, sea levels would rise about 7.4 meters (24 feet); if the entire Antarctic Ice Sheet melted, sea levels would rise about 60 meters (200 feet).

- The Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets also influence weather and climate through their influence on ocean circulation and their effect on winds in the polar regions.

- The ice comprising an ice sheet flows from higher to lower elevations under the influence of gravity. The same is true for alpine glaciers, ice caps, and icefields.

Ice caps

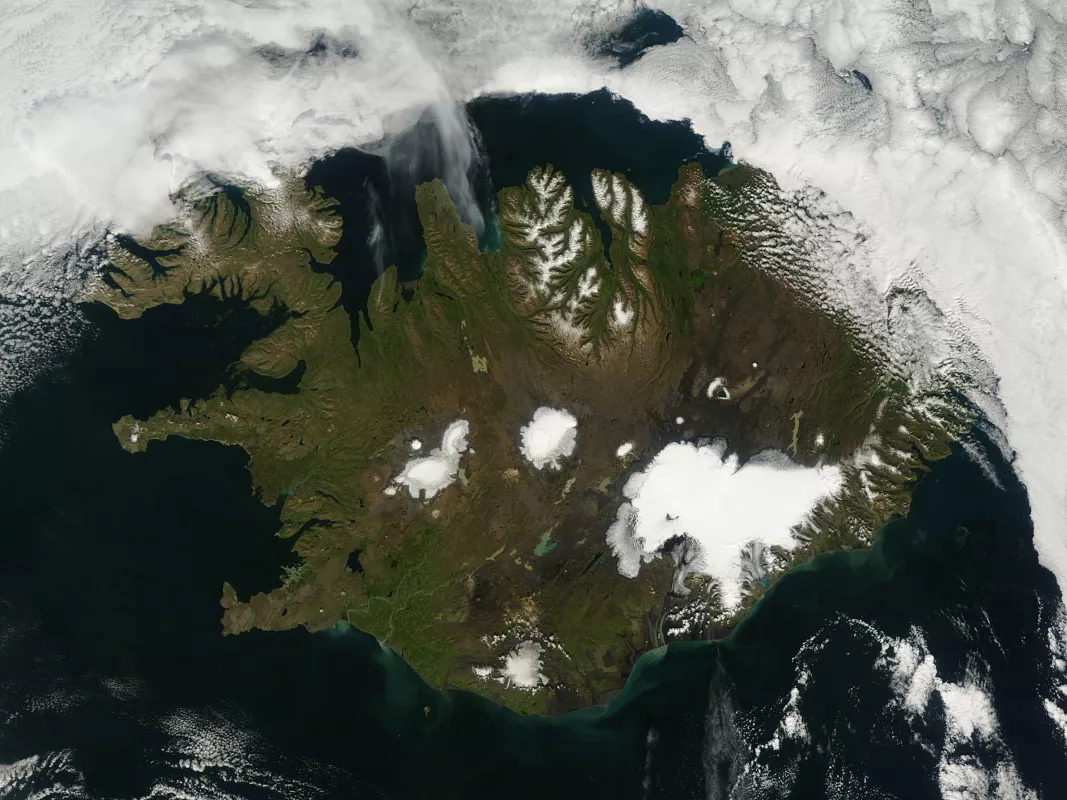

An ice cap is a body of glacial ice covering less than 50,000 square kilometers (19,300 square miles) and typically comprises several merged glaciers. Like ice sheets, ice caps tend to spread out in dome-like shapes as opposed to occupying a single valley or set of connected valleys. Good examples of ice caps include the Agassiz Ice Cap on Ellesmere Island, and the Barnes Ice Cap on Baffin Island.

- Ice caps form primarily in the high-altitude polar and subpolar mountain regions.

- Northern Europe is home to many ice caps, such as the Vatnajökull ice cap in Iceland and the Austfonna Ice Cap in the Svalbard Archipelago of Norway, the latter of which is the largest ice cap (in area) in Scandinavia.

- The largest ice cap in the world is the Severny Island ice cap, part of the Novaya Zemlya Archipelago in the Russian Arctic.

- Ice caps are also found in mountain ranges like the Himalayas, Rockies, Andes, and the Southern Alps of New Zealand.

- Icefields, such as the Juneau Icefield, are similar to ice caps but their ice flow is influenced by mountains.

Ice shelves & icebergs

As ice sheets and alpine glaciers extend out to the ocean, they form thick plates of ice that float on the ocean called ice shelves. These extensions of ice connect to a landmass. Ice shelves exist mostly in Antarctica and Greenland, as well as in far northern Canada. Icebergs are chunks of ice that break off alpine glaciers or ice shelves and drift in the oceans.

- Both ice shelves and icebergs raise sea level, but only when they first leave land and push into the water. Once present in the water, they do not raise sea levels even as they melt because they are already afloat.

- Iceberg calving under warming climate conditions can reach catastrophic proportions. In 2002, a total of 3,250 square kilometers (1,255 square miles) of Antarctica's Larsen B Ice Shelf disintegrated; larger than the size of Rhode Island, the mass shattered in only a few weeks, sending thousands of icebergs into the ocean.

- Icebergs carry sediments and dust into the ocean, which offer nutrients for algae and plankton growth. These plankton blooms provide food for krill, small shrimplike creatures eaten by larger animals like penguins, seals, whales, and seabirds.

- Biologists, climatologists, and glaciologists study ice shelves and icebergs to understand their impact and significance for wildlife, climate, and Earth as a whole.

Sea ice

Sea ice forms from frozen seawater. The point at which seawater freezes depends on its salinity, but the typical freezing point is about -1.8 °C (28.8 °F). Most sea ice forms in the Arctic Ocean and the Southern Ocean surrounding the Antarctic Ice Sheet.

- Sea ice does not raise sea level when it melts because it is already floating in ocean water.

- Bare sea ice reflects between 40 and 60 percent of the sun’s rays hitting its surface.

- Snow typically covers sea ice. Snow is even more reflective than the ice, reflecting up to 90 percent of the sun’s energy. The open ocean, by contrast, only reflects up to 10 percent of the sun’s energy. Thus, Arctic and Antarctic sea ice keeps the polar regions cool and helps moderate global climate.

- Sea ice fills a central role in the lives and customs of those living in the Arctic, who use sea ice for hunting and traveling. Sea ice also protects coastal areas from erosion by damping ocean waves. In areas with less sea ice, storms on the Arctic Ocean can generate much larger waves, damaging shorelines and Arctic communities.

- Sea ice creates a platform for algae to thrive, sustaining krill—shrimp-like crustaceans—and other animals.

- Scientists and local experts observe sea ice to study the effects of climate change.