Ice Shelves

Quick Facts

What is an ice shelf?

Ice shelves are floating tongues of ice that extend from glaciers grounded on land.

How do ice shelves form?

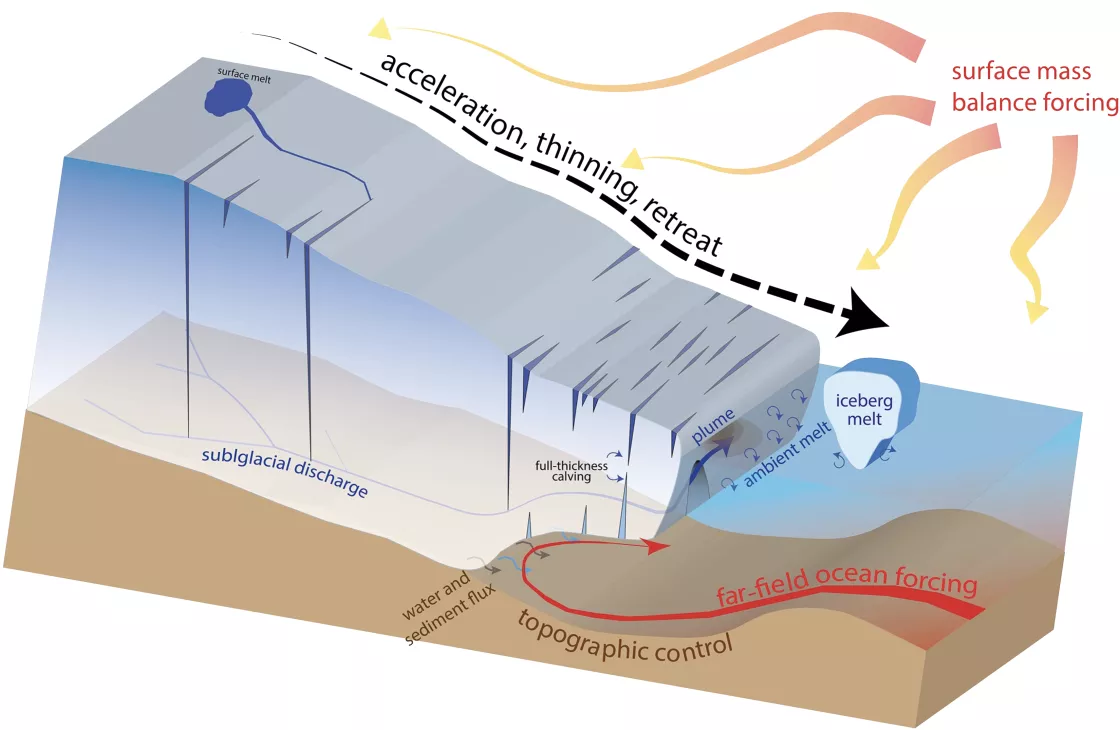

Glaciers flow under their own weight out to a coastline and onto the ocean surface, pushing and feeding an ice shelf. Snow falls on a glacier, adding mass to the glacier, which pushes further out to the ocean. However, there are two other ways ice shelves form: sea ice and local snowfall can form an ice shelf, and ice shelves can form out of a composite of glacier and fast ice, which is sea ice that attaches to a coastline.

Together, an ice shelf and the glaciers feeding it can form a stable system, with the forces of outflow and back pressure balanced.

How do ice shelves shrink?

Two types of events occurring on ice shelves have attracted the attention of scientists. One kind is iceberg calving, a natural event. The other kind is disintegration, a newly recognized phenomenon associated with climate change.

Why do ice shelves matter?

Higher temperatures can destabilize this system by increasing glacier flow speed and—more dramatically—by disintegrating the ice shelf. Without a shelf to slow its speed, the glacier accelerates. After the 2002 Larsen B Ice Shelf disintegration, nearby glaciers in the Antarctic Peninsula accelerated up to eight times their original speed over the next 18 months. Similar losses of ice tongues in Greenland have caused speed-ups of two to three times the flow rate in just one year.

While calving or disintegrating ice shelves do not raise ocean levels, the resulting glacier acceleration does, and this poses a potential threat to coastal communities around the globe. Worldwide, more than 100 million people currently live within 1 meter (3.3 feet) of average sea level. According to the United Nations' Ocean Conference held in 2017, more than 600 million people, or about 10 percent of the world’s population, live in coastal areas that are less than 10 meters (33 feet) above sea level. The conference also mentioned these facts on sea level rise:

- Between 1901 and 2010, global sea level rise increased at an accelerating rate and recent sea level rise appears to have been the fastest in at least 2,800 years.

- From the 1980s through the 2010s, 75 percent of the sea level rise could be attributed to glacier mass loss and ocean thermal expansion. This gives Antarctica alone the potential to contribute more than a meter (3.3 feet) of sea level rise by 2100 and more than 15 meters (49 feet) by 2500.

- Sea level rise leads to coastal erosion, inundations, storm floods, tidal waters encroachment into estuaries and river systems, contamination of freshwater reserves and food crops, loss of nesting beaches, as well as displacement of coastal lowlands and wetlands. In particular, sea level rise poses a significant risk to coastal regions and communities.

- Almost two-thirds of the world's cities with populations of over five million are located in areas at risk of sea level rise.

- The potential costs associated with damage to harbors and ports caused by sea level rise could be as high as $111.6 billion by 2050 and $367.2 billion by the end of the century.

In total, Greenland contains enough ice to raise sea level by 7 meters (23 feet), and Antarctica holds enough ice to raise sea level by 57 meters (187 feet). While these ice sheets are unlikely to disappear anytime soon, even partial loss of the grounded ice could present a significant problem. In the coming decades of a climate warming era, ice shelves and ice tongues are likely to play a prominent role in changing the rate of ice flow off the Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheets.

What is calving?

Calving occurs when chunks of ice break off from ice shelves, glaciers, and icebergs. Unique to Antarctica, giant flat icebergs, or tabular icebergs can occur. The process can take a decade or longer. Some are the size of small countries or US states. One giant iceberg, named A68, broke off Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf in 2017. At the time, this was the world’s largest iceberg, about the same area as Delaware and larger than the nation of Luxembourg: 109 miles long and 31 miles wide. In late 2020, the iceberg, still massive, was en route to collide with South Georgia Island in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Scientists feared that the iceberg could become grounded near the island, disrupting local wildlife like penguins and seals from foraging in the ocean. This kind of ecosystem disaster has occurred in the past, as when a large iceberg blocked emperor and Adélie penguins in McMurdo Sound from foraging in 2004. However, polar species are resilient—although many chicks died, in a few years the colonies had mostly recovered.

Stresses arising from flowing past rocky islands, or interactions with glaciers, can cause large cracks called rifts to form. Rifts are a kind of ice fracture that penetrates the full thickness of a floating ice plate. Eventually, the rift can extend until a large area of floating ice is completely separated from the ice shelf. These chunks are called icebergs. In the case of Antarctica's Amery Ice Shelf, the calving area resembles a loose tooth.

What is ice shelf disaggregation?

Warm ocean water can break up an ice shelf into many pieces. The scientific community is adopting the term “disaggregation” in the most extreme cases where an ice shelf gets to the point that it looks like spilled Chiclets, a brand of candy-coated chewing gum.

How can I learn more?

NSIDC Resources

NSIDC Data

NSIDC also distributes open access scientific data sets related to ice shelves.