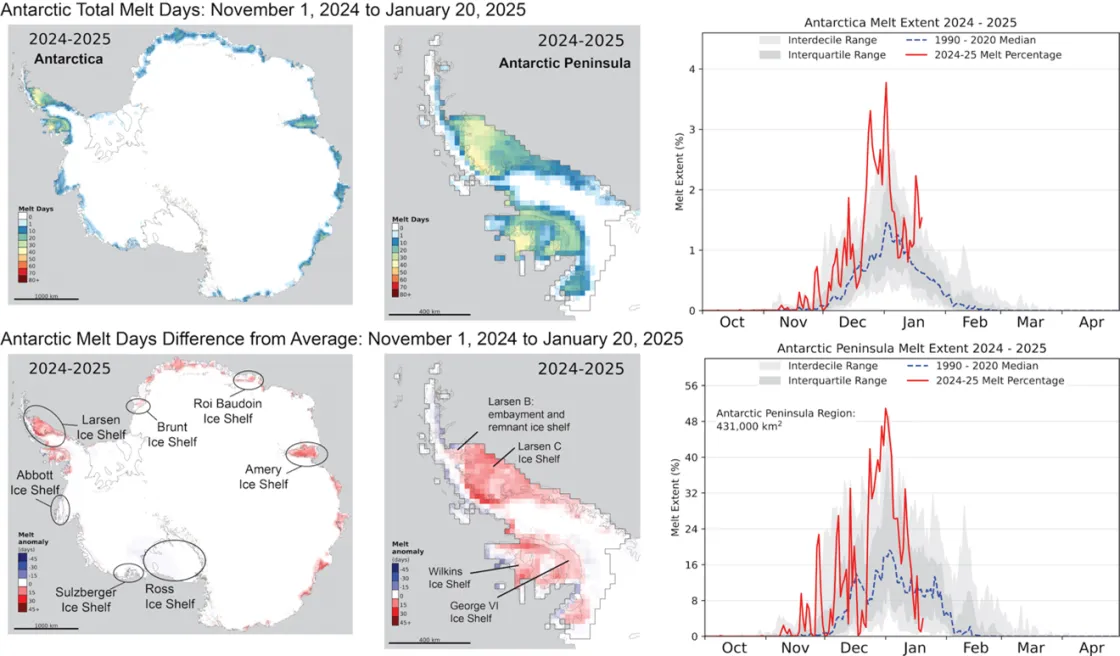

Surface melting for the Antarctic ice sheet appears to have set a record for the 46-year satellite observation period on January 2, 2025. All areas of the Antarctic coast that generally see significant summertime melting continue to accumulate melt days at a faster-than-average pace, except along the northern West Antarctic ice shelves, which are now near-average.

Current conditions

Days after our last report, surface melting exceeded the all-time record set just a week earlier in December with an even greater melt extent on January 2, 2025, with 3.7 percent of the Antarctic ice sheet showing melt that day, and 49 percent of the Antarctic Peninsula sub-region experiencing melt (as determined by our satellite passive microwave method). Melting continued to occur most days in January in the western Larsen C, Amery, and Totten Ice Shelves, although the overall area of daily melt extent for the ice sheet dropped through the course of the month. This was especially true in the Peninsula, which showed near-zero surface melting on January 19. Widespread melting along the Dronning Maud Land coast and Amery Ice Shelf on January 17 and 18 led to a second melt extent daily record for the continent.

Conditions in context

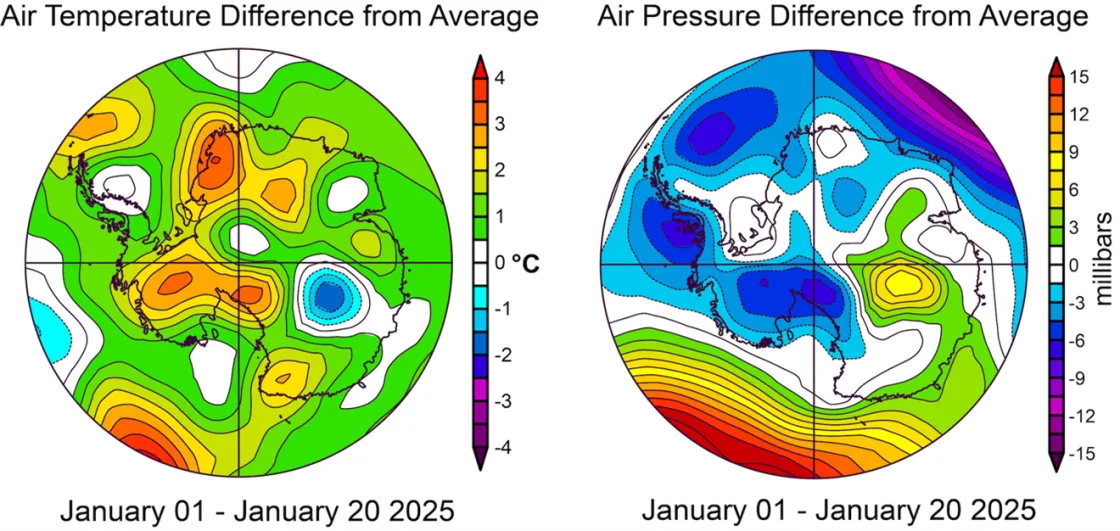

The persistently high melt extents for much of December and January this season are due to widespread above-average air temperatures across the continent. However, warmth over the Peninsula has been less extreme and air temperatures have been near-average over portions of the Wilkes Land coast. Air circulation patterns explain some of the warmest regions (e.g., to the southeast of low-pressure areas, or southwest of high-pressure regions), but in general are atypical of the continent.

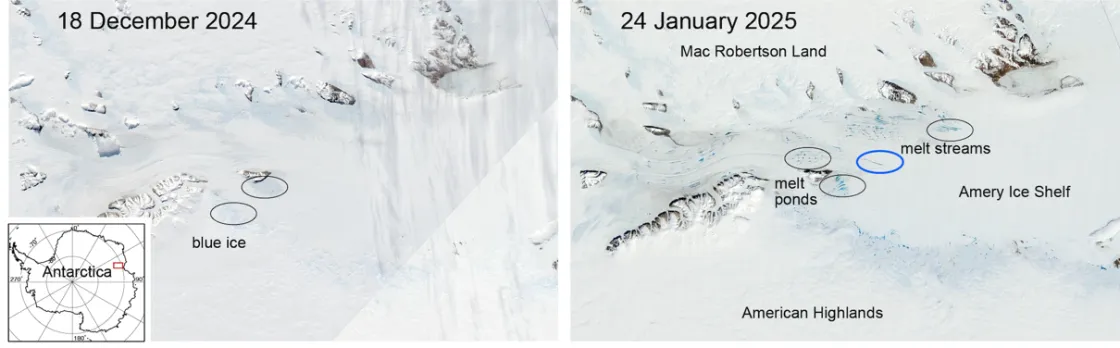

Extensive melt ponds and streams form on the Amery for the first time in five years

Warm and frequently sunny conditions led to extensive surface melting and ponding on the Amery Ice Shelf. As melting progressed into January, several areas formed streams, where meltwater saturated the underlying snow and firn and moved downstream (generally northward) until they reached less saturated snow and soaked into the sub-surface firn.

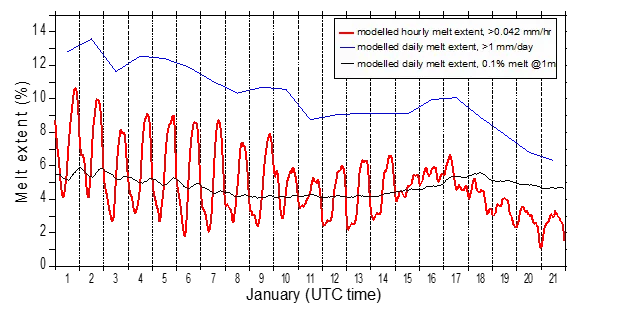

Timing is everything for mapping melt

Comparisons of the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) melt algorithm with other algorithms can show significant differences in overall extent, although the relative extent variations, such as timing of seasonal highs and lows, tend to broadly agree. The differences are likely related to the timing of the passive microwave satellite passes used to determine melt extent in the NSIDC approach.

As an illustration of how important satellite overpass timing can be, relative to local time on the surface, the climate model Modèle Atmosphérique Régional (MAR) version 3.12 was used to calculate hourly melt extent over the month of January, from January 1 to January 21, 2025. Hourly surface melt extent over the continent is strongly controlled by insolation, or incoming solar radiation, which varies with the height of the sun even in the eternal daylight of the Antarctic coast. The model determines the hourly surface melt extent by using a calculated production of 1/24 of a millimeter per hour, equivalent to 0.042 millimeters or about 0.002 inches. Thus, the difference in measured melt extent from passive microwave satellite data can vary greatly if the overpasses occur in local morning, afternoon, or late evening. Moreover, the estimated physical threshold for detecting water in the passive microwave satellite algorithm is different from the climate model threshold.