High air temperatures observed over the Barents and Kara Seas for much of this past winter moderated in February. Overall, the Arctic remained warmer than average and sea ice extent remained at record low levels.

Overview of conditions

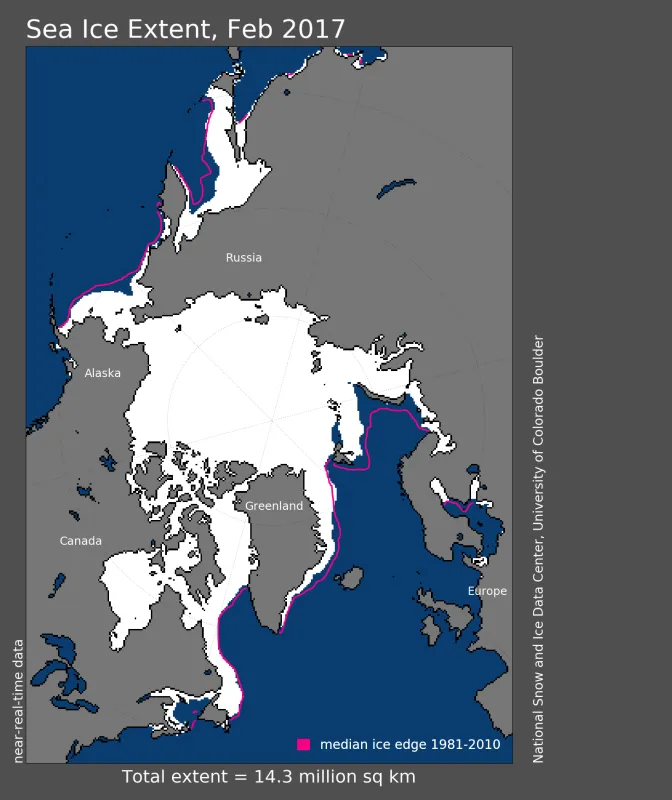

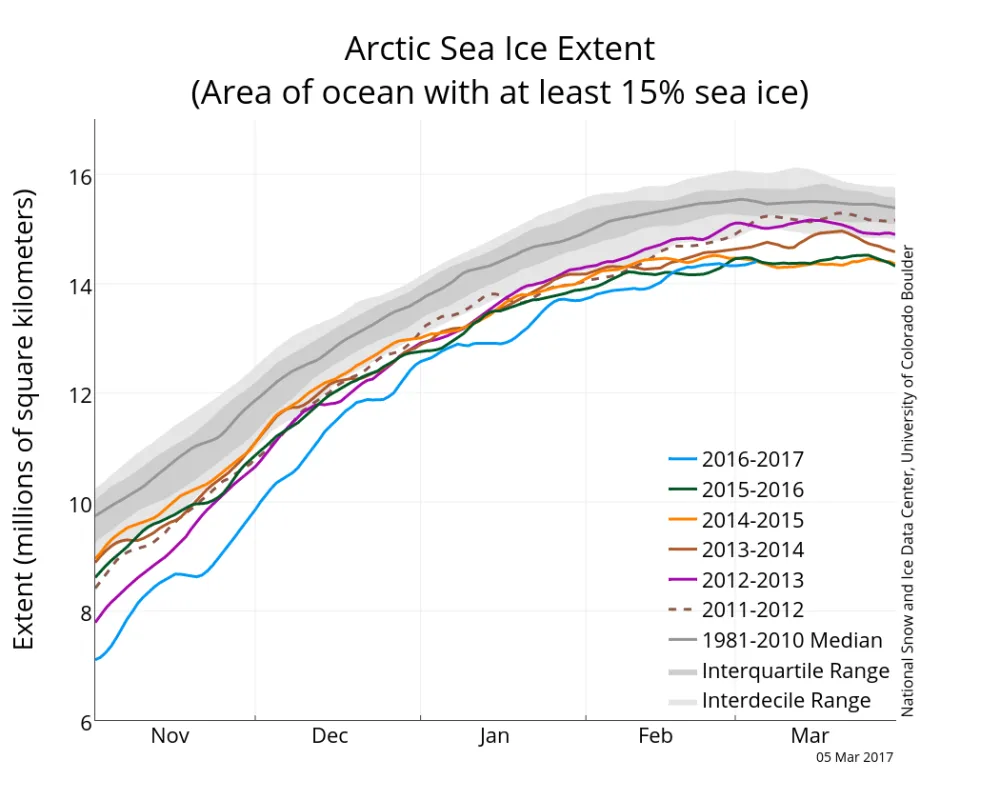

Arctic sea ice extent for February 2017 averaged 14.28 million square kilometers (5.51 million square miles), the lowest February extent in the 38-year satellite record. This is 40,000 square kilometers (15,400 square miles) below February 2016, the previous lowest extent for the month, and 1.18 million square kilometers (455,600 square miles) below the February 1981 to 2010 long term average.

Ice extent increased at varying rates, with faster growth during the first and third weeks, and slower growth during the second and fourth weeks. Most of the ice growth in February occurred in the Bering Sea, though extent in the Bering remained below average by the end of the month. Sea ice extent in the Sea of Okhotsk substantially decreased mid-month before rebounding to almost typical levels at the end of the month. Overall, however, the ice retreated in this region. Extent in the Barents and Kara Seas remained low through the month as is has all season, with little change in the ice edge location.

Conditions in context

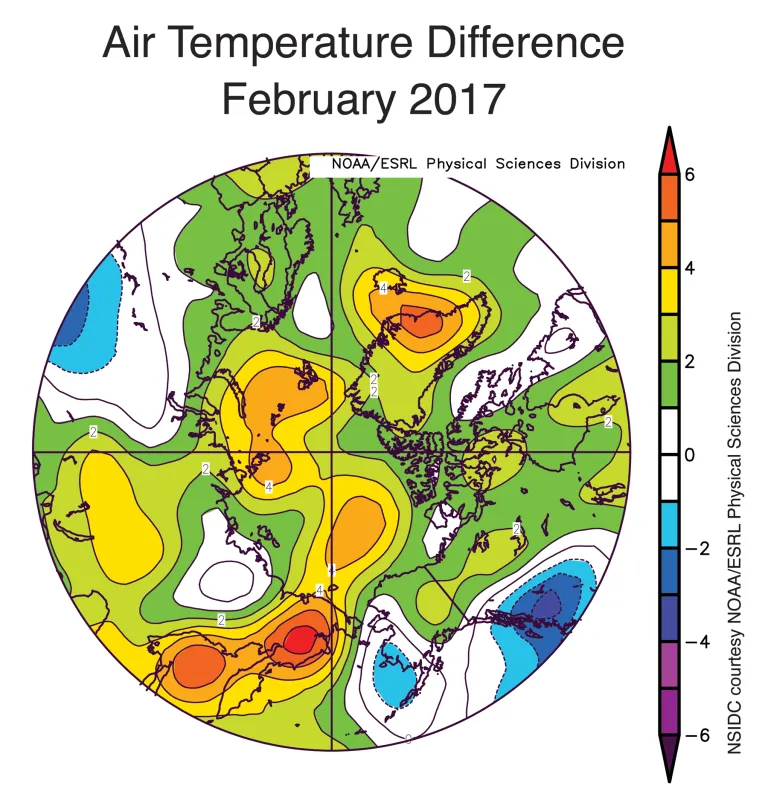

Air temperatures at the 925 hPa level (approximately 2,500 feet above sea level) remained 2 to 5 degrees Celsius (4 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) above average over the Arctic Ocean. The high air temperatures observed over the Barents and Kara Seas for much of this past winter moderated in February. February air temperatures over the Barents Sea ranged between 4 to 5 degrees Celsius (8 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) above average, compared to 7 degrees Celsius (13 degrees Fahrenheit) above average in January. Recall that these January temperature extremes were associated with a series of strong cyclones entering the Arctic Ocean from the North Atlantic, drawing in warm air. Sea level pressure in February was nevertheless lower than average over much of the Arctic Ocean. Sea level pressure was higher than average over the Bering Sea and just north of Scandinavia.

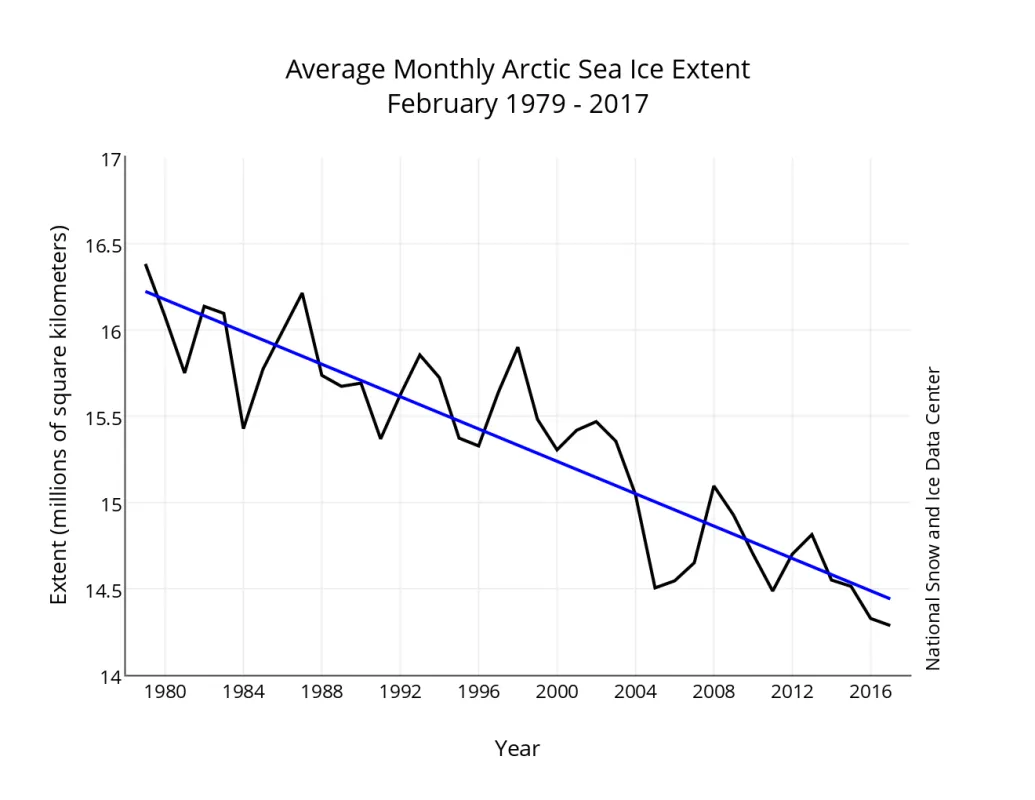

February 2017 compared to previous years

The linear rate of decline for February is 46,900 square kilometers (18,100 square miles) per year, or 3 percent per decade.

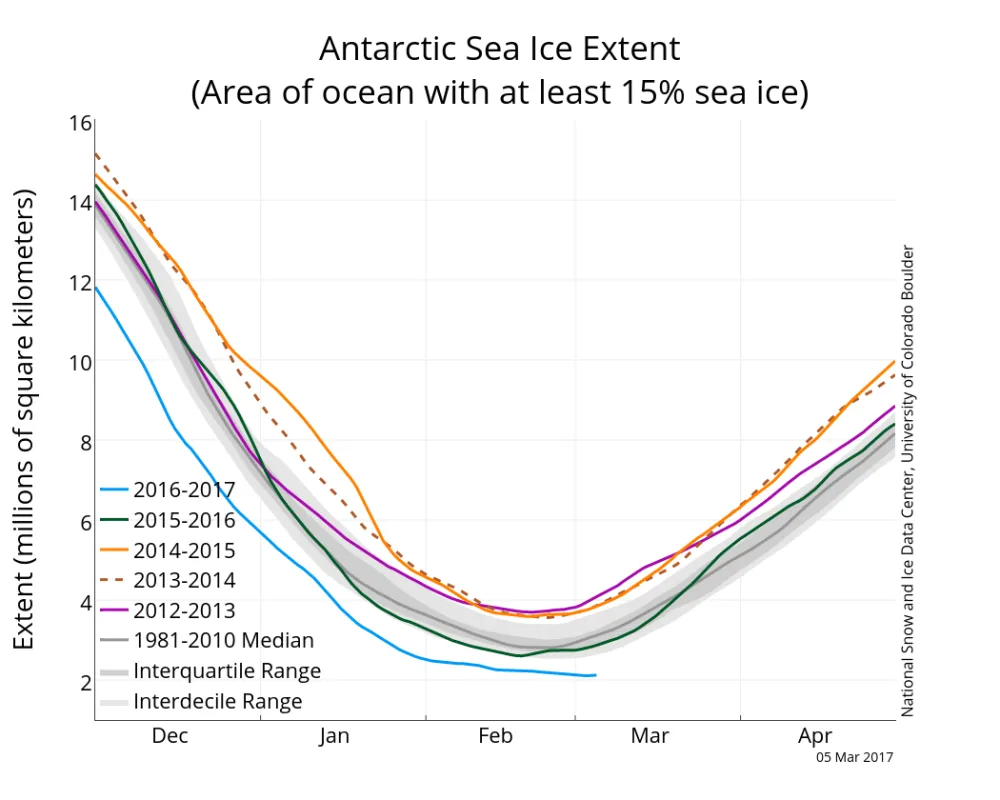

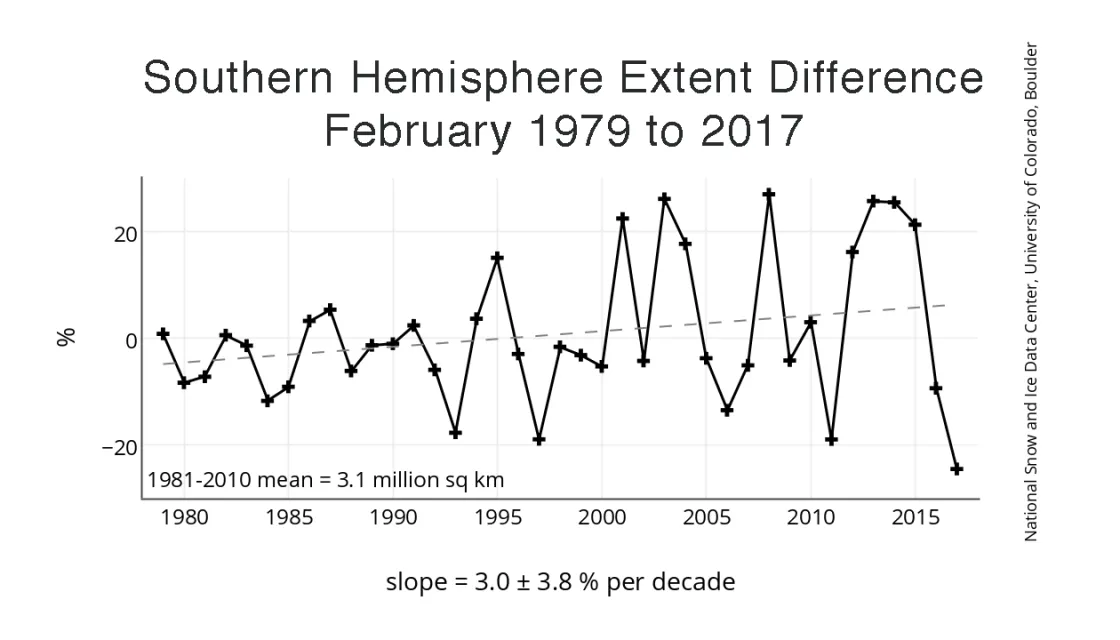

Antarctic minimum extent

Antarctic sea ice is nearing its annual minimum extent and continues to track at record low levels for this time of year. On February 13, Antarctic sea ice extent dropped to 2.29 million square kilometers (884,000 square miles), setting a record lowest extent in the satellite era. The previous lowest extent occurred on February 27, 1997. By the end of February, extent had dropped even further to 2.13 million square kilometers (822,400 square miles). The record lows are not surprising, given Antarctic sea ice extent’s high variability. Just a few years back, extent in the region set record highs (Figure 4b).

Sea ice extent was particularly low in the Amundsen Sea, which remained nearly ice-free throughout February. Typically, sea ice in February extends at least a couple hundred kilometers along the entire coastline of the Amundsen. Near-average ice extent persisted in the Weddell Sea and in several sectors along the East Antarctic coast.

Continuity of the sea ice record

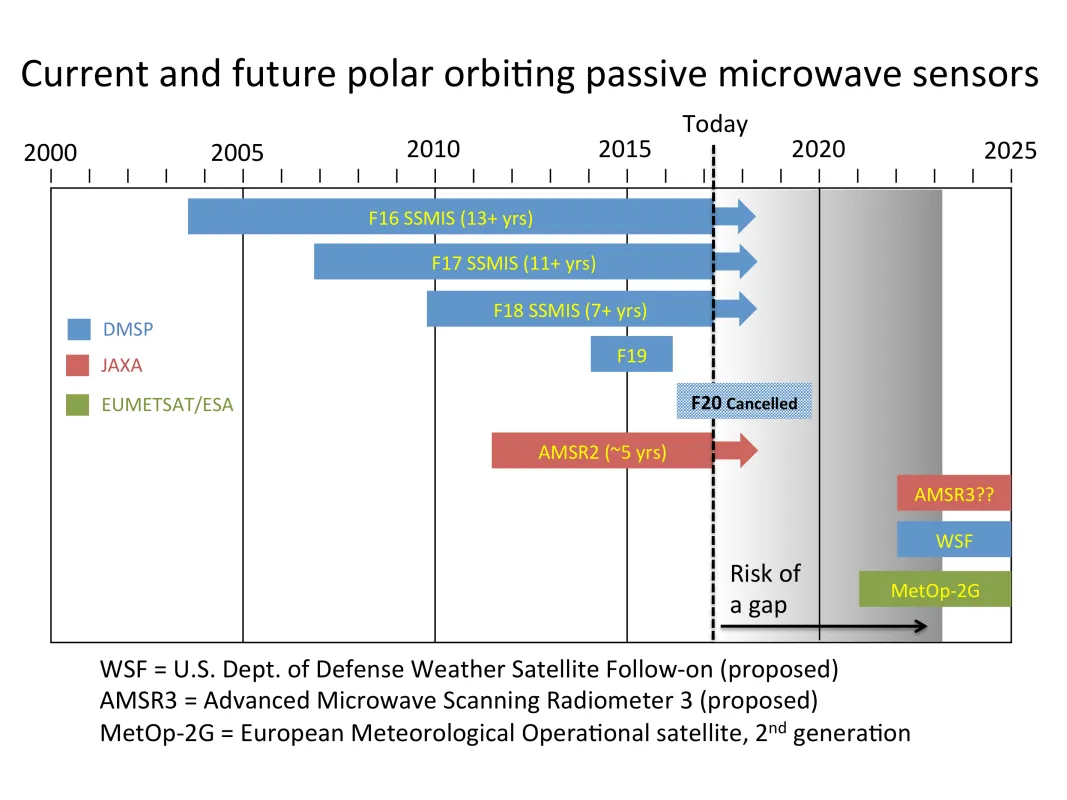

As noted last year, the sensor that NSIDC had been using for sea ice extent, the Special Sensor Microwave Imager and Sounder (SSMIS) on the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) F17 satellite, started to malfunction. In response, NSIDC switched to the SSMIS on the newer F18 satellite. Later, F17 recovered to normal function, though it recently started to malfunction again.

The DMSP series of sensors have been a stalwart of the sea ice extent time series, providing a continuous record since 1987. Connecting this to data from the earlier Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer (SMMR) results in a continuous record starting in 1979 of high quality and consistency. However, with the issues of F17 and last year’s loss of the newest sensor, F19, grave concerns have arisen about the long-term continuity of the passive microwave sea ice record. Only two DMSP sensors are currently fully capable for sea ice observations: F18 and the older F16; these two sensors have been operating for over 7 and 13 years respectively, well beyond their nominal 5-year lifetimes.

The only other similar sensor currently operating is the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2), which is approaching its 5-year design lifetime in May 2017. NSIDC is now evaluating AMSR2 data for integration into the sea ice data record if needed. Future satellite missions with passive microwave sensors are either planned or proposed by the U.S., JAXA, and ESA, but it is unlikely that a successor to the DMSP series and AMSR2 will be operational before 2022. This presents a growing risk of a gap in the sea ice extent record. Should such a gap occur, NSIDC and NASA would seek to fill the gap as much as possible with other types of sensors (e.g., visible or infrared sensors).