Arctic Rain On Snow Study (AROSS)

ROS Impacts

Though rain on snow (ROS) events may only last a few hours or days, their impacts on Arctic wildlife and communities can linger for months, years, and even generations. Animals such as reindeer, caribou, and musk oxen survive the bitter Arctic winters, with some of the lowest temperatures on Earth, by digging through snow to graze on herbs, lichen, and grasses beneath. ROS events can form an impenetrable barrier of ice, cutting wildlife off from the vegetation beneath. Starvation and mass die-offs may result, leaving the communities that depend on the animals for food, money, and even transportation, stressed and isolated.

How Rain on Snow (ROS) events impact wildlife

On land, ROS events influence the population dynamics of species that seek shelter in the snowpack, including lemmings, voles, owls, ptarmigan and grouse. In marine environments, when rain on snow falls early in the breeding season, it can melt subnivean lairs and increase cub mortality for polar bears and ringed seals.

Ungulate species, however, are perhaps impacted the most. In 2003, a ROS event on Banks Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago led to the starvation of 20,000 musk oxen. The musk oxen were forced to expand their grazing range in search of food, resulting in some wandering onto sea ice where they were left stranded at sea. This major event impacted the health and population size of future musk oxen generations. With depleted fat and protein reserves, few musk oxen maintained healthy pregnancies, leading to few births the following summer. The lack of new calves and decline in overall herd health could not sustain the population, leading to continued population decline for years after the initial ROS event.

Though ROS events may only last a few hours or days, their impacts on Arctic wildlife and communities can linger for months, years, and even generations. Animals such as reindeer, caribou, and musk oxen survive the bitter Arctic winters, with some of the lowest temperatures on Earth, by digging through snow to graze on herbs, lichen, and grasses beneath. ROS events can form an impenetrable barrier of ice, cutting wildlife off from the vegetation beneath. Starvation and mass die-offs may result, leaving the communities that depend on the animals for food, money, and even transportation, stressed and isolated.

How ROS events impact people

Over two dozen local communities have herded reindeer for centuries, but for many this way of life is dying out. In the past two decades, reindeer populations have declined by more than half, down to 2.3 million. Already practiced by few, reindeer herding now faces more challenges as ROS events increase in a warming climate. Reindeer have reserves of fat to sustain them through winter, but too much disturbance leaves the animal vulnerable to disease, attack, and unsuccessful pregnancies.

For the Sami of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia, reindeer husbandry is a way of life. Other herding peoples include the Chukchi, Evenki, Eveny and Nenets in Siberia, the Dukha and Tsaatan in Mongolia, and the Ewenki in China. Throughout Alaska’s Seward Peninsula and Bering Sea region, reindeer herding continues to be practices by several Iñupiat and Yup’ik communities. Some herders across the Arctic only use the animal for its milk and transportation, while others honor the animal by letting no part go to waste: its sinews stitch fur and skin into clothes, shoes, blankets, and tents; its antlers are honed for knives; and even its stomach may turn into a cooking pot.

What ROS events do to infrastructure

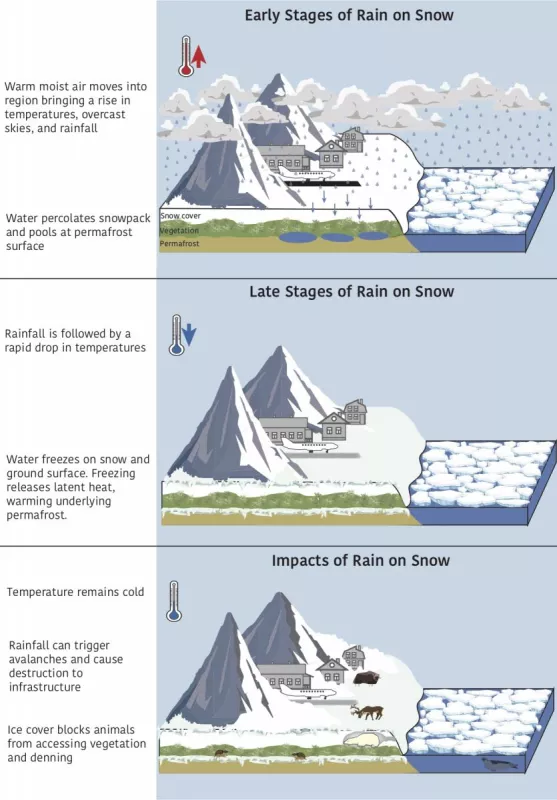

Rain on snow events create additional impacts on infrastructure in the Arctic. Mild ROS events can have temporary impacts such as icing local community runways, making travel difficult or impossible, preventing the delivery of supplies, and critical services like health care. However, ROS events can cause significant damage to infrastructure. For example, in 2012, heavy rains from a ROS event in Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, induced avalanches that destroyed infrastructure in the city of Longyearbyen. Additionally, the rain percolated through the snow cover to the ground surface, warming the permafrost beneath. Since this 2012 ROS event, the permafrost in the area has been warming at accelerating rates, linking the ROS to this warming trend.

A catastrophic ROS event example

Yamal Peninsula, Russia

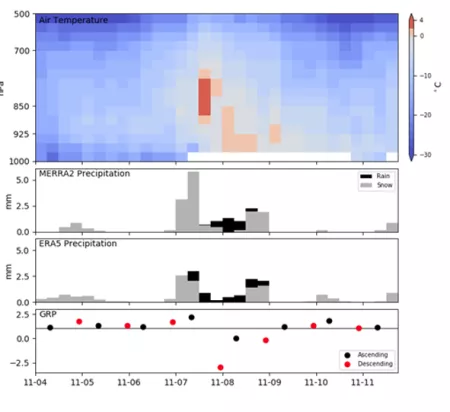

A rain on snow event over most of the southern Yamal Peninsula, Russia, that occurred between November 5 to 10, 2013, eventually led to the starvation of 61,000 reindeer out of a herd of 275,0000. Herders who had lost most or all of their animals were stranded on the tundra because of the lack or reindeer to haul their camps. They resorted to full time subsistence fishing and borrowed breeding livestock to rebuild their herds.

On November 8, a tongue of warm air, with temperatures above the melting point, moved over the region. Warm air was accompanied by 24 hours of rain. The plot shows 925 hPa air temperature (filled contours) and sea level pressure (black isobars) for November 8. The warm air mass can be seen in red hues. In the following days, air temperatures over the southern part of the peninsular then dropped below the melting point, causing liquid water in the snowpack to freeze, creating an ice crust.

Reference

Forbes, B. C., et al. 2016. Sea ice, rain-on-snow, and tundra reindeer nomadism in Arctic Russia. Biology Letters, 12, doi: 10.1096/rsbl2016.0466.