By Natasha Vizcarra

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) is well known for its data on frozen parts of the Earth. But soon, it will have data on something more warm-blooded.

Scientists on a mission to measure Greenland’s melting ice sheet have been exploring heat-seeking cameras typically used by the police, the military, and pilots. They were using it to scrutinize Greenland’s land and sea ice, but stumbled on a rather unusual use for the science instrument.

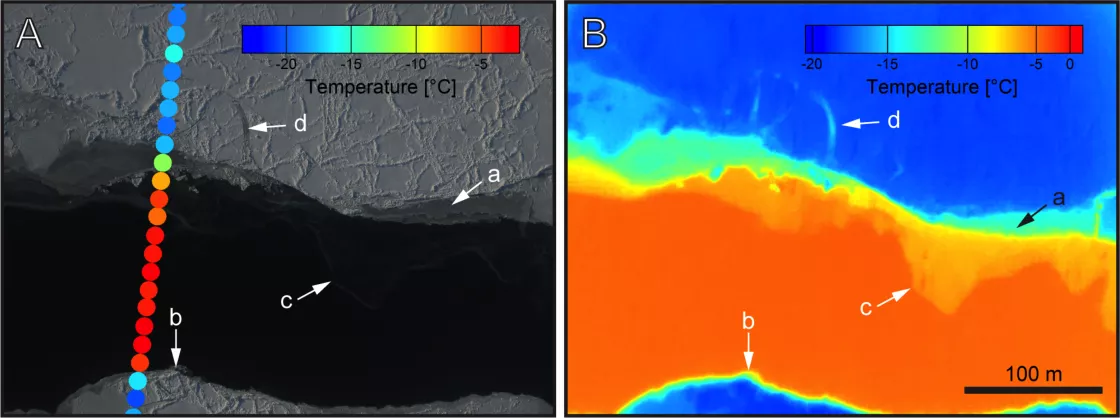

On May 12, 2015, scientists from NASA Operation IceBridge were flying over the eastern coast of Greenland—one of many flights to measure the island’s ice thickness. The researchers were also testing the Forward Looking Infrared (FLIR) camera that had just been added to their suite of instruments. The FLIR Cam’s thermal imaging helps map very thin ice that other sensors haven’t been able to see. En route to their next transect, they spotted a herd of large, furry animals down below.

“We’re flying over some muskoxen right now!” the C-130 pilots announced over the aircraft intercom to the team hunkered in the plane’s cargo area.

Muskoxen are large bovines that live in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic. They have large, thick coats and weigh from 350 to 600 pounds. Remote sensing expert Jim Yungel sat in the cargo with other scientists. “We had a limited view of the outside world,” he said. “The back of a C-130 has very few windows.” So they scrambled to peer at a camera, called the Continuous Airborne Mapping By Optical Translator (CAMBOT), and saw an image of the muskoxen and their hoof prints in the snow.

“Just for the heck of it, another scientist checked the FLIR Cam,” Yungel said.

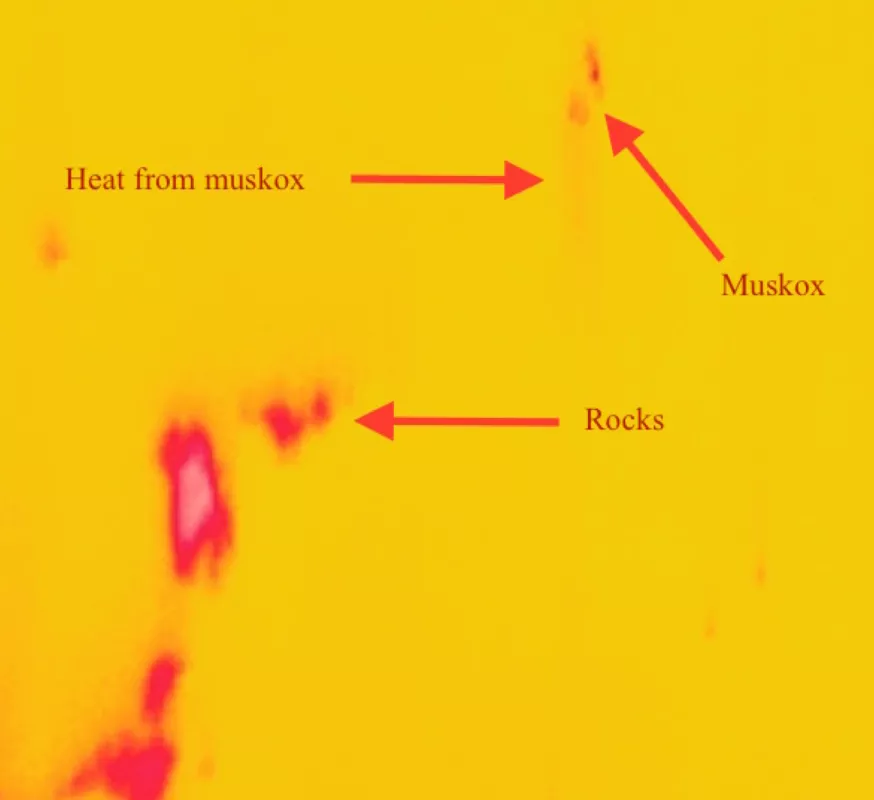

Alexey Chibisov, an instrumentation engineer, first saw the heat signatures of some rocks that the muskoxen had passed. Then the scientists noticed a blur where the animals should have been.

“We paired up the CAMBOT image and the FLIR Cam image and scaled it up,” Yungel said. “The red blur was residual heat from where the muskoxen were walking through the snow. I included the images in the Situation Report that we write after each flight, and many folks seem interested in this unusual use of the science instrumentation.”

Police departments and the military often use FLIR cameras when they are looking for a lost child, or someone who is trying to hide. Pilots also use FLIR cameras to steer their aircraft at night or in thick fog. The camera senses infrared radiation emitted by a heat source and creates a “picture” of those radiation signatures. Living and nonliving things all have radiation signatures, so a FLIR image can paint an outline of a scene using these signatures.

“It has shown great potential for scientific land and sea ice use,” Yungel said. “I don’t know what kind of information can be gleaned from the muskox images, but a lot of folks in Greenland study Arctic wildlife. There’s a lot of potential in that too.”

Operation IceBridge’s FLIR data will be used with other mission data to create a comprehensive map of the Greenland ice sheet’s thicknesses. However, FLIR data will also be available as a separate data set. All IceBridge data are archived and distributed by NSIDC. Yungel will be one of the first to pore through the images. “I’m looking forward to discovering some more unusual targets,” he said.