by Audrey Payne

As her name suggests, Tasha Snow, a glaciologist, former US Navy officer, and PhD student at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder), has a passion for the cryosphere. Despite initially believing she would become a marine biologist and setting out to do so in college, Snow took a course on climate change her senior year that changed her perspective and career trajectory, turning her attention to how the oceans impact climate. She then traveled to Antarctica while studying for her master’s degree and her focus shifted to understanding the changes occurring in the polar regions, such as how the oceans interact with ice sheets and contribute to rising seas, where it remains. This keen interest in the world’s frozen places, along with her work as a scientist, recently led Snow to join a two-month scientific expedition to one of the most unstable glaciers in the world: Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica.

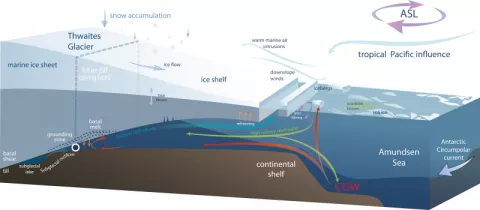

In January 2019, Snow traveled to Thwaites with the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a five-year, $50 million partnership between the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). Over the past 30 years, the amount of ice flowing out of Thwaites has nearly doubled and the surface height of the glacier has dropped by many tens of feet, making it one of the fastest-retreating glaciers in Antarctica. Models predict it could begin to collapse within the next 50 to 100 years and potentially raise global sea levels by up to two feet over the next century, putting coastal cities and communities around the world at risk.

Concerns over the potential collapse of Thwaites drive the ITGC research, which seeks to answer two big questions: How much of this glacial ice is a threat for raising global sea levels, and how fast might the glacier release this ice? More than 150 scientists and students will study Thwaites Glacier, roughly the size of Florida, and its adjacent ocean region to explore marine sediments, measure currents, and examine the glacier’s movement over the landscape below.

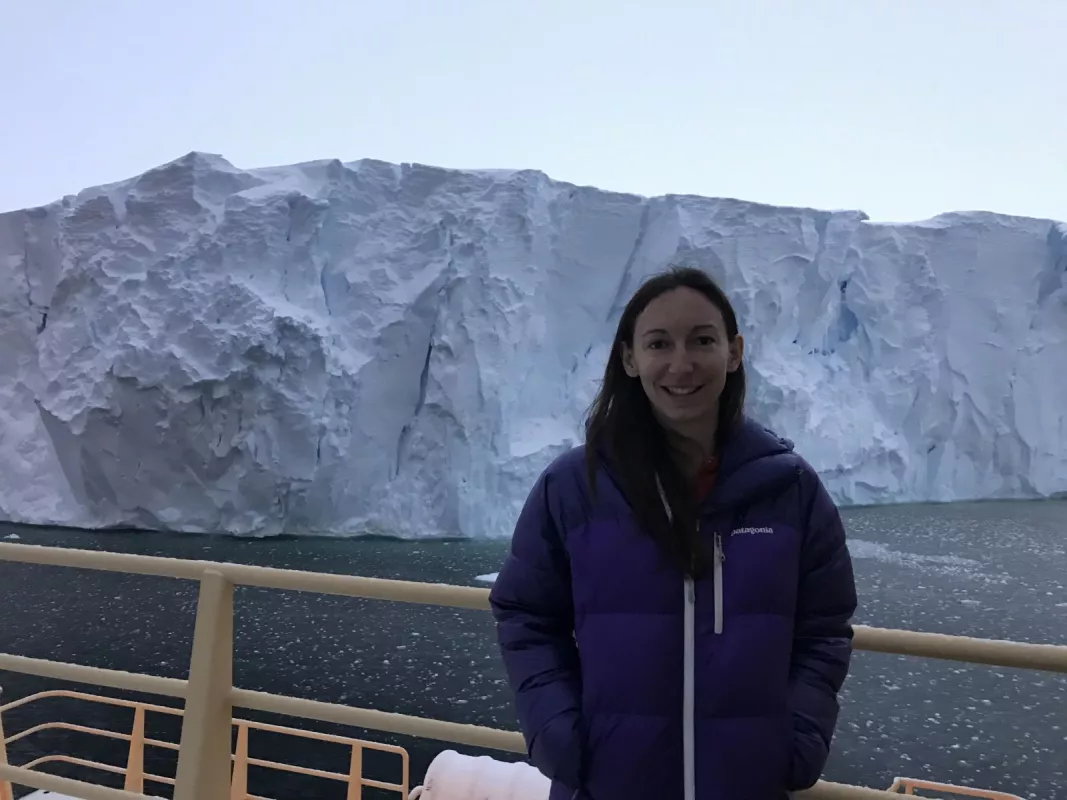

Snow joined this expedition along with 23 other scientists, 30 crew and support staff, and three media personnel, all of whom were out to sea for 55 days. Though Snow normally uses satellite imagery to study how glaciers and oceans interact and have changed over time, she took on a different position during the expedition to fill a needed role aboard the ship: resident media facilitator.

Upon her return to solid ground, I sat down with Snow to learn more her trip to Thwaites. Here is what she had to say.

1. How were you able to join this expedition?

This trip offered an opportunity to breach another frontier—there’s so little known about that part of the world. No one had been to this specific area in front of Thwaites before; the ocean floor had never even been mapped. I had some background in public affairs, leadership, and managing people from my years in the United States Navy. Combining that with the fact that as a scientist, I understand what scientists need, made me a natural fit to be the media facilitator.

2. What was it like out on the water?

We had to cross the Drake Passage, which has the roughest seas in the world, and despite my time in the Navy, I get awful seasickness. We went through a storm that had 35-foot waves, and when the seas hit their worst, our mattresses began to slide back and forth in the bunks while we were in them. It was definitely “Type II fun”—no fun while it was happening, but fun to talk about later.

After getting across the Drake, excitement comes in the form of iceberg sightings. Some are the size of a football field and taller than the ship. At first, you see one, then you start to see a few more off in the horizon, and then they’re everywhere, all migrating away from Antarctica. It feels like a super highway—like when you’re driving to the city from a rural area and you start seeing more cars as you get closer to the city. Except instead of cars, they’re icebergs.

3. What were the best parts of the journey?

The best, along with seeing the towering front of Thwaites, was being in a place that no one had ever been or mapped before on the western side of Thwaites Ice Shelf. Every day was a new discovery.

The wildlife was also incredible. There were seals and penguins everywhere. If you ever needed a break on the ship, you could just go up to the bridge and watch the penguins. They’re so curious that they would come right up to you to see what you were doing. I also saw my first breaching humpback whale, which took my breath away.

4. What was it like seeing Thwaites for the first time?

Breathtaking. We got there first thing in the morning and the ship was only a few hundred meters from the edge of the ice, traveling parallel to it with the ice cliff looming next to us. It was fascinating to see those ocean and glacier processes up close and to be able to compare that to what I had seen in the satellite imagery in my own research.

5. Can you explain what the scientists aboard the ship were studying?

ITGC is comprised of eight research projects and four were represented on this research cruise. The scientists aboard aimed to explore the ocean currents, reconstruct the history of ocean and glacier changes in the area, and determine where the warm ocean water in the area is, which can erode the glaciers from below and make them unstable.

6. What did the scientists learn during the expedition?

Most of the data will not be published for another year or two. However, we had a few “big accomplishments” on the ship. We tagged 12 seals, attaching small instrument packs to them that record ocean conditions when they dive. They’ve already taken hundreds of readings from areas that we were unable to reach during our trip, and will continue to take ocean measurements for the next year. We also mapped over 1,200 square miles of sea floor in front of Thwaites and took over 26 sediment cores, which will be used to reconstruct the history of Thwaites.

Some of the projects accomplished more than we initially thought they would because there was such strong collaboration between the scientists and organizations. We accomplished so much more working together on these projects than we could have done otherwise because of the wide range of expertise and thoughtful collaboration taking place.

7. How concerned should we be that Thwaites is on the brink of collapse?

There have been a few studies that suggest the glacier is already unstable, and it has continued to rapidly lose ice to the ocean since those publications came out. Because there has been so much change and there’s so much ice sitting behind Thwaites, it’s certainly very scary and concerning to me. Some of the changes occurring at Thwaites are unprecedented in comparison to what we’ve seen in other parts of Antarctica. The big question is whether the rates of ice loss will continue or get worse in the future. It’s really a giant wild card for climate change.

8. Will you be going back to Thwaites during another year of the partnership? If so, will you be in the same role?

I don’t have plans to go back yet, but if the opportunity arose, I would love to.

ITGC’s Science Coordination Office (SCO) is based at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and the Earth Science Observing Center (ESOC), both part of Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at CU Boulder. The British Antarctic Survey is also a partner in the SCO.