By Michon Scott

Explorers have dreamed of trade shortcuts across the Arctic Ocean for centuries. That shortcut was more easily imagined than achieved, thanks to Arctic weather, polar darkness, and near-constant sea ice. In the mid-nineteenth century, a two-ship, 129-man expedition led by John Franklin disappeared into the Arctic's hostile environment. Tales of that expedition still hung over Roald Amundsen’s plans decades later, at the dawn of the twentieth century. But Amundsen succeeded where others had failed, finding both the Northwest Passage and the magnetic North Pole. The journey he led took over two years, winding through the narrow southern channels of the Canadian Archipelago.

During the twentieth-century Cold War, submarines skulked under Arctic ice, preparing for the possibility of a cold war turning hot. Over the same period, science missions occurred on the sea ice surface, and subsistence hunters took advantage of the sea ice for hunting and fishing. Still, thick, tough ice curtailed most ship traffic. The East-West Arctic shortcut remained elusive.

Things change.

Arctic sea ice has steadily declined since the start of the continuous satellite record in November 1978, leaving the Arctic Ocean less icy and, to some, more inviting. More ships can squeeze through the Northwest Passage through the Canadian Archipelago, though ice clogs the route through most of the year. Growing ship traffic passes through the Northern Sea Route, which stretches through Russia’s exclusive economic zone, from Novaya Zemlya to the Bering Strait. (A longer route through the region, often called the Northeast Passage, includes the Barents Sea.) The Arctic Report Card: Update for 2022 devoted a special essay to rising ship traffic in the Arctic Ocean, noting summertime increases in the exclusive economic zones of six Arctic nations. Between 2009 and 2018, ship traffic increased 12.5 percent in the Russian Federation’s zone, 15.1 percent in Iceland’s, and a remarkable 47.6 percent in Norway’s.

Although sea ice retreat makes the Arctic more attractive to cargo ships, cruise ships, and military vessels, the region remains challenging to navigate, even during the long days of summer. Storms, shifting ice, and other factors make planning both essential and difficult.

The NASA NSIDC Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC) and NOAA@NSIDC archive and distribute data sets relevant to maritime navigation in the polar regions. NSIDC does not provide real-time, up-to-the-minute data products for operational navigation. NSIDC does, however, offer a wealth of products with historical observations, often spanning several decades or longer. These products provide climatological data that are indispensable for seasonal and long-term planning, risk assessments, and feasibility studies. Whether you’re planning a shipping season, supporting coastal community planning, or assessing insurance costs, NSIDC products provide decades of climatological context to inform smart, safe decisions.

Ice hazards and maritime safety

In today’s Arctic, hazards are increasing, and not just because of more ships in the region. As sea ice retreat opens more of the ocean to ship traffic, the warming driving that retreat amplifies threats of errant ice bodies. Higher air and water temperatures encourage more iceberg calving in places where ice and ocean water meet.

After the Titanic’s infamous collision with an iceberg in April 1912, what is now the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention established the International Ice Patrol (IIP). The IIP began monitoring iceberg activity in 1913, but SOLAS appointed the IIP to monitor icebergs only in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland—not a larger area and not sea ice. Over a century later, in 2024, the International Ice Charting Working Group (IICWG) drafted a preliminary white paper recommending expanded monitoring. Such changes will take time to implement, though.

While navigators await expanded monitoring of ice hazards, data sets archived at NSIDC help fill the gap and can provide context for long-term planning in a changing Arctic.

Long-term trends and planning tools

Imagine your employer has tasked you with planning shipping activities in the Arctic for the coming season. Careful planning is not just beneficial to your employer by reducing risks and costs, it may also be a requirement to operate in the region. For example, the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters, or Polar Code, went into effect on January 1, 2017. It includes mandatory measures for obtaining a Polar Code vessel certificate, which include addressing safety and the prevention of pollution in the polar regions. It addresses topics ranging from ship design to safety training to voyage planning.

For real-time, operational information related to Arctic navigation, NSIDC recommends contacting the US National Ice Center, the Canadian Ice Service, or another regional service. In addition, NSIDC’s webpages on the International Ice Charting Working Group offer links to the latest charts and a list of participating agencies.

NSIDC archives data sets reflecting the work done by the International Ice Patrol spanning several decades.

- International Ice Patrol (IIP) Iceberg Sightings Database provides iceberg data collected by the IIP from January 1, 1960, to September 29, 2021.

- International Ice Patrol Annual Count of Icebergs South of 48 Degrees North, 1900 to Present provides iceberg data from October 1, 1899, to September 30, 2021.

- International Ice Patrol Annual North Atlantic Iceberg Summaries and Reports provides observations based on the “iceberg year,” which runs from October 1 through the following September 30. The data set currently provides temporal coverage from October 1, 2023, through September 30, 2024.

SIGRID-3 is a vector data format (shapefile) for sea ice charts, established by the World Meteorological Association. NOAA@NSIDC offers multiple data sets in SIGRID-3 format, as well as in gridded format.

- US National Ice Center Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice Charts in SIGRID-3 Format describes sea ice concentration and ice type from January 6, 2003, to present.

- Canadian Ice Service Arctic Regional Sea Ice Charts in SIGRID-3 Format describes sea ice concentration from January 1, 2006, to present.

- US National Ice Center Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice Concentration and Climatologies in Gridded Format describes sea ice concentration in both polar regions from January 6, 2003, to present.

Climatological indicators and Ice thickness or route timing

Want to plan a trip across the Arctic effectively? You need to understand when shipping lanes are most amenable to traffic—where there is open water, or at least weak ice—and how conditions may vary by region and year.

Arctic sea ice typically drops to its lowest annual extent near the end of the Northern Hemisphere summer, and this coincides with optimal shipping conditions, although precise timing varies. The ice edge is defined by concentration—a percentage or percentage range defining the boundary between ice-filled and ice-free. The ice edge can shift quickly with winds, currents, and weather. Knowing the exact location of the ice edge helps ships avoid hazards, save time and fuel, and safely reach their destinations. Ice can drift into shipping lanes within hours or melt away to open new routes, making reliable, up-to-date information essential for route planning.

NOAA@NSIDC and the NSIDC DAAC archive products that provide mariners, researchers, and planners with reliable ice edge information, as well as data that serve as climatological indicators for long-term route timing.

Ice edge

- IMS Daily Northern Hemisphere Snow and Ice Analysis at 1 km, 4 km, and 24 km Resolutions provides daily maps of Northern Hemisphere snow and sea ice produced by US National Ice Center (USNIC) analysts. These maps can identify overall ice extent, improve understanding of seasonal trends, inform route planning, and provide data to support decision making. Observations are typically updated daily although precise timing varies.

- Multisensor Analyzed Sea Ice Extent - Northern Hemisphere (MASIE-NH) Daily Image Viewer is a user-friendly interactive interface offering near-real-time ice extent maps: MASIE maps. It displays the Multisensor Analyzed Sea Ice Extent - Northern Hemisphere (MASIE-NH) data set, which is derived from the most recent full day of Interactive Multisensor Snow and Ice Mapping System (IMS) data from the USNIC. USNIC analysts work using a combination of human-interpreted synthetic aperture radar (which can see through clouds), visible satellite imagery (which can see at high resolution), and visual inspection and synthesis by a trained professional.

- US National Ice Center Daily Marginal Ice Zone Products focus on a marginal ice zone (MIZ) defined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as the outer region of pack ice where wave energy penetrates. This band of ice cover is interpreted by the US National Ice Center as ice that ranges from 10 percent to 80 percent sea ice concentration. It can move rapidly depending on weather conditions.

Both the MASIE-NH and MIZ products are particularly useful in locating the dynamic sea ice edge. Knowing the location of the sea ice edge is valuable since it often drives where navigation is—and is not—feasible. MIZ products consist of analyst-synthesized daily extent maps whereas MIZ is a World Meteorological Organization (WMO)-defined band of sea ice where concentrations range from 10 to 80 percent. Although similar products can be obtained directly from the US National Ice Center, NSIDC adds value, for example, by providing plain-language user documentation explaining why ice edge locations may appear different, depending on the product used.

Ice thickness, age

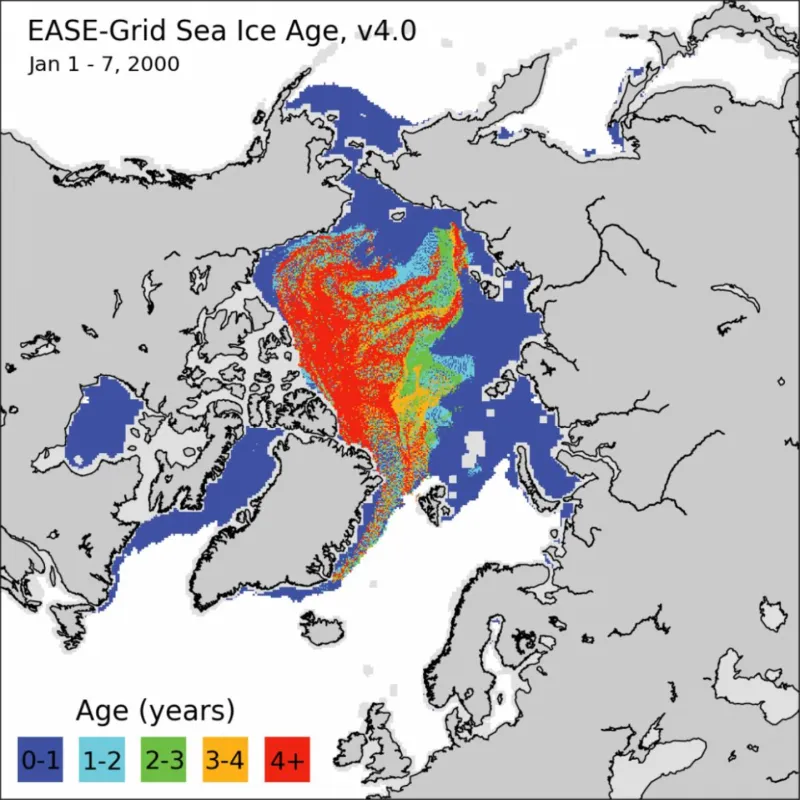

Sea ice thickness varies from paper thin to thicker than a one- or even two-story-house. Sea ice tends to thicken over time before reaching a plateau around four years. So, sea ice age serves as a proxy for sea ice thickness. Multiple products archived at NSIDC provide thickness data. By helping users identify areas of thick or thin ice, these products assist in identifying high-latitude routes amenable to ship traffic.

- ATLAS/ICESat-2 L3A Sea Ice Freeboard Quick Look supports navigation route planning by helping users identify areas of thinner ice. Freeboard is the portion of sea ice that protrudes above the water surface. High freeboard indicates relatively thick sea ice that would be difficult to navigate. Note this product has limitations: roughly three-day latency, uncertainty added by snow cover on the sea ice, and sparse spatial coverage.

- EASE-Grid Sea Ice Age uses sea ice motion and extent data to estimate sea ice age. This data set provides weekly estimates of sea ice age, from January 1, 1984, to present, with the most recent data in a Quicklook product. The age estimates do not encompass the Northwest Passage through the Canadian Archipelago, but they do cover the Northern Sea Route north of Russia.

- Arctic Sea Ice Seasonal Change and Melt/Freeze Climate Indicators from Satellite Data provides historical perspective, March 1, 1979, to February 28, 2018, rather than near-real-time data, but it shows historical variations in the timing of melt and freeze-up.

- On-Ice Arctic Sea Ice Thickness Measurements by Auger, Core, and Electromagnetic Induction, from the Late 1800s Onward provides sea ice thickness measurements derived from drill holes, gauges, thermistor strings, and surface electromagnetic induction. Its temporal coverage ranges from September 4, 1879, to September 29, 2016.

- Sea-ice Thickness and Draft Statistics from Submarine ULS, Moored ULS, and a Coupled Model provides estimates of mean values of sea-ice thickness and sea-ice draft computed from multiple data sources. Its temporal coverage ranges from January 1, 1979, to December 31, 2004.

- Unified Sea Ice Thickness Climate Data Record, 1947 Onward provides observations as possible of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice draft, freeboard, and thickness. Its temporal coverage ranges from January 1, 1947, to January 1, 2017.

Near-real-time data

Visible Infrared Imager Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Sea Ice Extent 6-Min L2 Swath 375m is Near Real Time (NRT) is available directly from NASA Earthdata. This data set harnesses visible light to deliver near-real-time imagery of sea ice extent. Because it relies on the same wavelengths human eyes can see, it is often obscured by clouds and/or polar darkness. When imagery is clear, it supports confirmation of sea ice location.

Enhanced-resolution remote sensing for ice conditions

Need to design a platform to operate in the Arctic? Need to engage in pre-season planning? You will need to understand how sea ice varies across time and space. Temperatures, storms, and ocean currents behave differently in Fram Strait, the Beaufort Gyre, and in the channels of the Canadian Archipelago. The approach that works in one region may not succeed in another. So, you need data that reflect regional differences.

Multiple products at NSIDC facilitate better understanding of sea ice variability. This understanding supports platform design and pre-season navigation planning.

- Calibrated Enhanced-Resolution Passive Microwave Daily EASE-Grid 2.0 Brightness Temperature ESDR is routinely used by the National Weather Service Alaska Sea Ice Program (ASIP). ASIP augments other data sources with brightness temperatures to support operational analyses in the Alaska region, supporting shipping, fishing, and other activities.

- A research project at the University of Wisconsin recently produced sea ice concentration fields for ASIP. ASIP users found the sea ice concentration fields especially useful in the Bering Sea and Bering Strait. Potential future product results from this project may include applications focusing on the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route.

- Other brightness temperature products include:

- DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS Daily Polar Gridded Brightness Temperatures. A 2023 study used this data set to explore when the Northeast passage (part of the Northern Sea Route) is open to ship traffic.

- AMSR2 Daily Polar Gridded Brightness Temperatures. This is a follow-on product extending that augments the data record from the DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS Daily Polar Gridded Brightness Temperatures data set. Temporal coverage for this product is from January 1, 2023, to present.

- ATLAS/ICESat-2 L3A Along Track Coastal and Nearshore Bathymetry is a new product with potential for future use in monitoring narrow, shallow channels through the Arctic, places where sea ice charts do not yet show much detail. Before planners can rely on this product, though, its use should be tested.

Organizations applying NSIDC data

Multiple organizations have used the ATLAS/ICESat-2 L2A Global Geolocated Photon Data product. One organization is Ocean Ledger, a specialized geospatial analytics company focused on nearshore coastal environments. Another is TCarta, a company offering hydrospatial and geospatial mapping systems. TCarta focuses on inland, coastal, and offshore environments.

Why these data sets matter

Sea ice retreat is opening the Arctic Ocean to more ship traffic and other human activities, but operating in the region remains complicated. Success depends on understanding both the opportunities and risks. NSIDC data archives are not just historical records—they are planning tools that help governments, industries, researchers, and communities navigate responsibly in one of the most challenging environments on Earth.

By providing decades of sea ice, iceberg, and climatological data, NSIDC enables safer shipping, smarter infrastructure planning, and better risk management in a rapidly changing Arctic.

Data sets at a glance

This list includes additional data sets not described in detail above. Note that some data sets augment others, e.g., NSIDC-0802 extends the data record for NSIDC-0001. Data sets that have an identifying number beginning with “G” are part of the NOAA@NSIDC collection; others are part of the NSIDC DAAC data offerings.

References

Lindsey, R. 2022. As sea ice retreats, more ship traffic is entering the Arctic high seas. NOAA Climate.gov. Accessed August 6, 2025.

International Ice Charting Working Group. 2024. Expanding Threat of Icebergs and Sea Ice to Safe Navigation. White Paper submitted by IICWG Task Team 2024-6.

International Maritime Organization. International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (Polar Code). Accessed August 6, 2025.

World Meteorological Organization. SIGRID-3: A vector archive format for sea ice charts. JCOMM Technical Report No. 23. Accessed August 6, 2025.