By Natasha Vizcarra

Recently, the National Snow and Ice Data Center acquired stacks of 49-year-old film rolls from a National Climate Data Center storage facility in North Carolina. “There were fifty cardboard boxes. Each contained ten rusty, dusty canisters, each containing 500 feet of 35-millimeter negative film,” said NSIDC technical services manager Dave Gallaher. “We really wanted these.”

NSIDC scientist Walt Meier, who studies the yearly waxing and waning of sea ice in the Arctic, said the old film from one of the first U.S. Earth-observing missions, the NASA Nimbus 1 satellite, could give scientists a deeper look back at climate. It happened that the dusty boxes of old film were dated August to September 1964. “This film contains basically the earliest satellite data we have of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice extent,” Meier said. But making those canisters of film talk would be no easy task.

Right place, right time

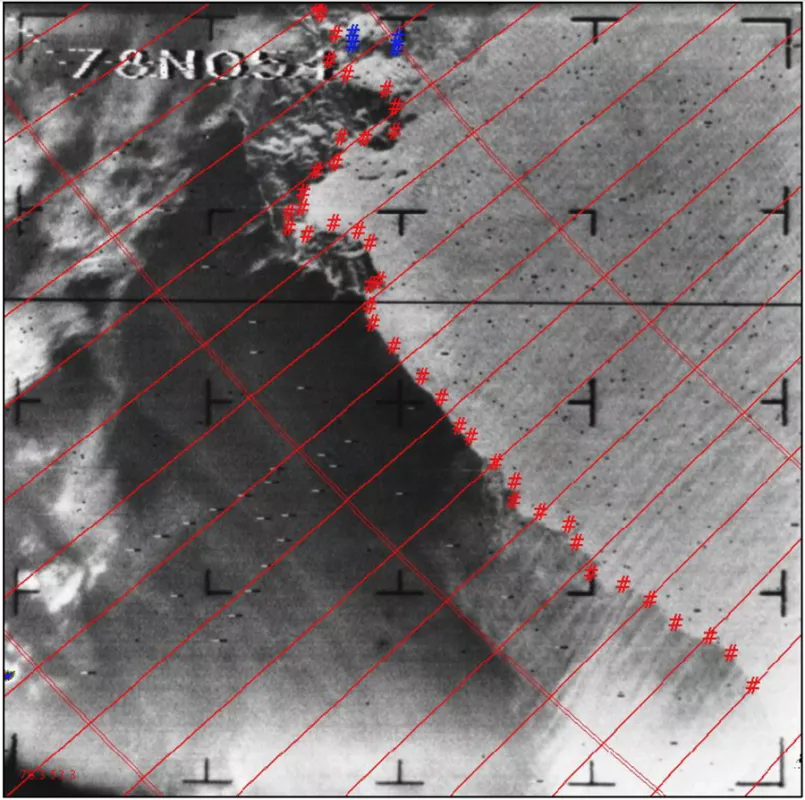

Scientists pay close attention to the ice in September, when it shrinks to its minimum extent. Arctic sea ice has long been recognized as a sensitive climate indicator, and has undergone a dramatic decline over the past thirty years. They currently depend on a satellite record that begins in 1979. Nimbus 1 was a test of weather satellite technology, including a video camera, so scientists could improve weather forecasts. Data specialist Garrett Campbell at NSIDC, “There were no fancy satellite sensors in 1964,” he said. “Scientists strapped a video camera to the Nimbus 1 satellite, sent it into orbit, and hoped for the best.” As it circled the globe in August and September, Nimbus 1 transmitted still shots of the Earth to a television monitor, which researchers photographed. After using the stills for weather forecasting research, scientists archived them in a secure storage facility.

In 2009, Gallaher stumbled on a NASA conference poster about the recovery of the film, and realized that it would have captured images of the Arctic sea ice minimum and the Antarctic maximum in 1964. Satellite records of Arctic sea ice extent only went as far back as 1978. There were other observations before 1978, like ice charts from naval ships, radiometer records, and other satellite imagery. None of these gave scientists a full view of the Northern Hemisphere. But the old film would. So Gallaher teamed with Meier and the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP) at NASA Ames Research Park to try to recover any information the old films might contain.

Arctic and Antarctic sea ice, 1964

Campbell, who spent the past two years examining shots from the film rolls, said the images would have been too overwhelming for researchers to process in the 1960s. “We didn’t have the computing power to handle all those images at that time,” Campbell said. “In 1964, researchers would have had to develop every single frame as a photograph and lay it out on the floor of a large room.”

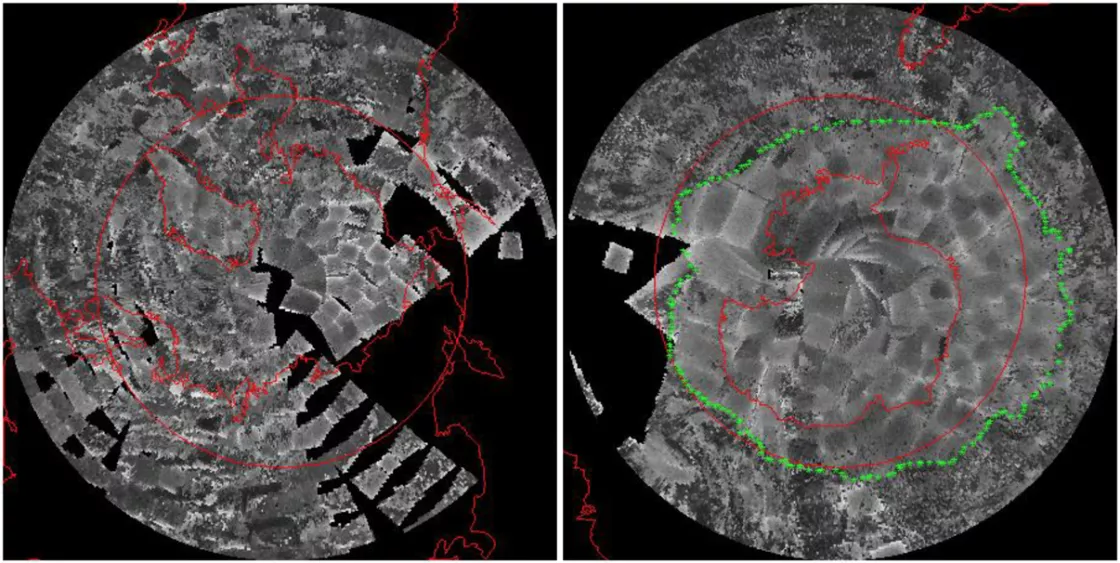

To get a good view of this composite of thousands of photographs, one would have to be standing a few floors above the photograph-covered floor, ideally on a very tall ladder. But with today’s technology, Campbell simply worked with two undergraduate students to scan close to 40,000 frames, made sure the images had the right latitude and longitude, and stitched the photos together in his computer. With those images, Campbell produced the first satellite maps of the sea ice edge in 1964 and an estimate of September sea ice extent for both the Arctic and the Antarctic.

According to the data, September Antarctic sea ice extent measured about 19.7 million square kilometers. “That’s higher than any year observed from 1972 to 2012,” Meier said. Figuring out the sea ice extent for the Arctic was more challenging. It was harder for the team to distinguish the ice edge along the coasts from snow or glacier-covered islands in the Canadian Archipelago. Also, there were not many images of Alaska and eastern Siberia to work from, so Campbell relied on old Russian and Alaskan ice charts. His analysis yielded a September 1964 Arctic sea ice extent of 6.90 million square kilometers. “The 1964 estimate is reasonably consistent with 1979 to 2000 conditions,” Meier said. “It suggests that September extent in the Arctic may have been generally stable through the 1960s and the early 1970s.”

NSIDC will be making these images, as well as high-resolution infrared data from the Nimbus 1 satellite, available to researchers beginning May 2013. The team has also acquired satellite imagery from Nimbus 2 and 3, and other satellites operating in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The result, hopefully, is a longer record of sea ice that Meier said would “put the dramatic decline of Arctic summer sea ice extent in a longer-term context” and prove useful to other scientists studying today’s changing climate.

Reference

Meier, W. N., Gallaher, D., and G. C. Campbell. 2013. New estimates of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice extent during September 1964 from recovered Nimbus I satellite imagery. The Cryosphere, 7, 699–705, doi:10.5194/tc-7-699-2013.