What is the Cryosphere?

Why it Matters

The cryosphere influences our world's climate, provides water for ecosystems, supports agriculture and is central to the daily lives of people, plants, and animals. Many animals and plants are uniquely adapted to snowy environments. At the same time, however, melting land ice leads to rising sea level.

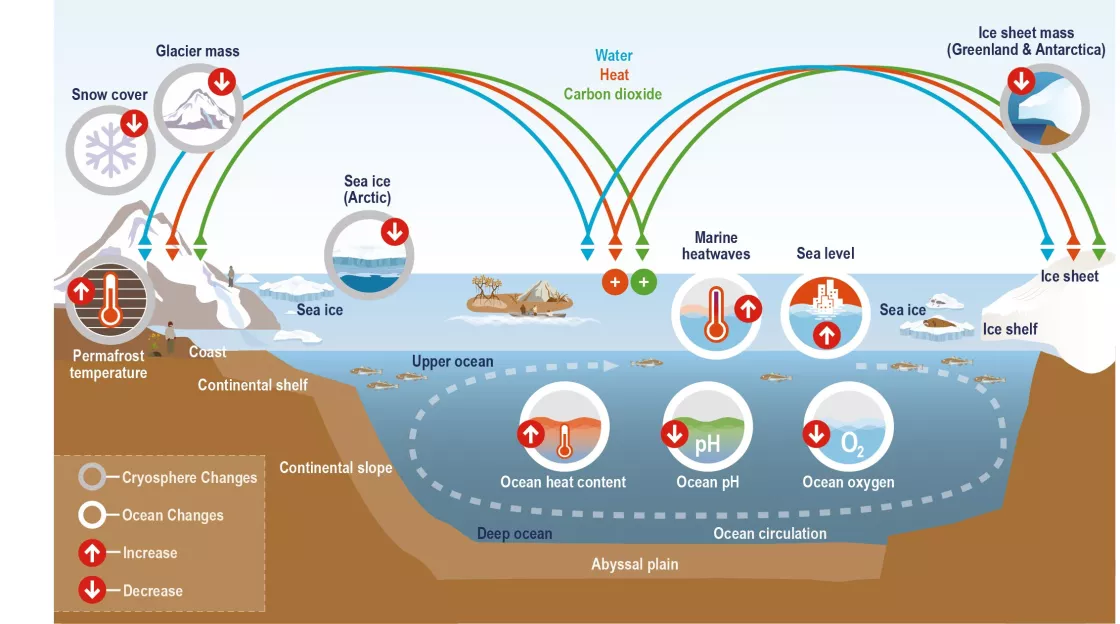

As part of the global climate system, snow and ice cool the planet by reflecting solar energy from their white surface back into space. Earth’s atmosphere, ocean, and landscapes are intricately connected to the cryosphere, affecting atmospheric circulation, precipitation, waterways, and mountain range erosion. Moisture transfers between frozen water and the atmosphere influence cloud cover formation, precipitation, and atmospheric circulation. Water composition, such as fresh meltwater flowing into a salty ocean, strongly affects ocean circulation. These back-and-forth exchanges influence long-term trends in climate and regional weather patterns.

Sea level rise occurs in one of two ways: when water temperatures increase, or when meltwater from snow or ice flows into the ocean. When water heats up, the space between molecules expands. So, when the ocean warms, sea level rises. About one-third of sea level rise is from thermal expansion of the ocean. When ice on land melts and its water runs into the ocean, or when a solid mass of ice like an iceberg calves into the ocean, sea level also rises. About 69 percent of total fresh water on Earth is stored in ice sheets, ice caps, and glaciers. Much of the remaining freshwater is groundwater, which itself can originate from melting ice.

Glaciers, seasonal snowfall, and ice play an important role in storing the planet’s freshwater reserves. For example, the Asian mountain ranges surrounding the Tibetan Plateau, like the Himalaya and Hindu Kush, represent a tremendous reservoir of perennial glaciers and seasonal snow cover. Each spring, rivers bulge with meltwater, mostly from snowmelt, delivering fresh water to over one billion people for drinking, agriculture, and hydropower. In areas like the Rocky Mountains of North America, seasonal snow sustains the Colorado River Basin, which delivers water to farms, cities, and ecosystems in much of the US Southwest.

As atmospheric greenhouse gas levels continue to rise, the atmosphere, global temperatures continue to rise. Since it only takes a slight uptick in temperature to go from frozen to thawed, the polar regions are especially sensitive to climate change. Data show that the Arctic is warming at two to four times the rate of the rest of the planet, depending on the calculation. A warmer planet thaws snow and ice faster and earlier in spring, exposing darker oceans and land. These dark surfaces then absorb more solar radiation, intensifying the impacts of climate change.

Where is the cryosphere?

The polar regions, the Arctic, and Antarctic, bookend the cryosphere, but it extends to vast areas in between.

The Arctic

The Arctic is an ocean basin largely surrounded by land. It includes the vast Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Frozen ground and permafrost ring the Arctic Ocean. Over the ocean, sea ice expands in the fall and winter and shrinks in the spring and summer. Permafrost is also found under the shallow shelf seas of the Arctic Ocean.

The Greenland Ice Sheet, second in size to the Antarctic Ice Sheet, covers about 80 percent of Greenland, the world's largest island.

Antarctica

At the other end of Earth, lies a massive icy landmass—the Antarctic Ice Sheet. This ice sheet covers about 13.7 million square kilometers (5.3 million square miles) or 98 percent of the continent. It is the largest mass of ice on Earth. The Antarctic Ice Sheet is much larger than the planet’s second-largest ice sheet, on Greenland. Antarctica is a polar desert, and the coldest, driest, and windiest continent. In some places, plates of thick floating ice extend into the ocean called ice shelves. The outer sections of these ice shelves periodically break off, or calve, and form icebergs. The icebergs float in the oceans, melting and falling apart as they drift into warmer waters.

And in between

The cryosphere also exists in places between the poles, especially at high elevations. For example, glaciers and snow cover Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, a mountain lying about 3 degrees (about 322 kilometers or 200 miles) south of the equator. The Asian mountain ranges surrounding the Tibetan Plateau, like the Himalaya and Hindu Kush, are known as Earth’s third pole because of the number of perennial glaciers and amount of snow found there.

About a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere’s land is underlain by permafrost, where the ground is frozen for at least two years. Nearly 85 percent of Alaska is underlain by a layer of permafrost. It is also widespread in the Arctic regions of Siberia, Canada, and Greenland and found in high-altitude regions like the Rocky Mountains, Tibetan Plateau, South American Andes, and New Zealand’s Southern Alps.

Glaciers are found in mountain ranges on every continent, except for Australia. Glacial ice, including alpine glaciers, ice caps, icefields, and ice sheets, cover about 10 percent of the planet, providing drinking water to billions of people.

Large parts of the Northern Hemisphere have seasonal snow cover. While snow melts shortly after falling in some areas, in cold areas and mountains, it accumulates through the winter. When the snowpack melts, rivers swell, providing water for irrigation, hydropower, agriculture, and recreation.

Lake ice is another part of the cryosphere. In some areas, lakes can remain frozen for months at a time.

How is the cryosphere changing?

Changes in the cryosphere provide direct visual evidence of global temperature changes. Water changing from solid to liquid and back often results in dramatic visual changes across the landscape as various snow and ice masses shrink or grow. Examples of these changes can be seen from the Arctic to Antarctica and nearly everywhere in between.

The cryosphere is an especially sensitive indicator of climate change. A study published in 2021 made a global estimate, for the first time, quantifying the extent by which sea ice, snow cover, and frozen ground cover Earth. The researchers then compared how climate change has impacted that extent. Between 1979 and 2016, Earth lost 87,000 square kilometers (33,000 square miles) of sea ice, an area about the size of Lake Superior, per year on average. The extent of the cryosphere matters because its bright white surface reflects sunlight, cooling the planet. Changes in the area and location of snow and ice can alter air temperatures, change sea levels, and even affect ocean currents worldwide.

In the Arctic

Scientists first began noticing changes in the Arctic in the 1980s, but it was not yet clear then if the response was a warming trend or natural variability. By the mid-1990s, however, it became clear that the rapid warming of the Arctic is a signal of human-caused climate change. Since 1990, the Arctic has warmed at two to four times the rate of the globe as a whole, depending on the region and season. This outsized warming is known as Arctic amplification. Several factors may be contributing to the Arctic’s extreme warming. As the Arctic Ocean loses its bright, white sea ice, more solar energy is absorbed by the much darker ocean surface. This means that, at summer's end, there is more heat in the upper ocean than there used to be. Before sea ice can form in the autumn and winter, this extra heat must be released back to the atmosphere, leaving it warmer. The formation of ice itself also releases heat back to the atmosphere. The Arctic atmosphere also resists vertical mixing, which holds the extra heat near the surface. Some research suggests that more ocean heat from the Atlantic Ocean is moving into the Arctic Ocean. finally, loss of snow cover of Arctic lands also leads to the absorption of more solar energy by land surfaces, also contributing to Arctic amplification.

Arctic amplification is not the only evidence of rapid climate change in the Arctic. The floating sea ice cover of the Arctic Ocean is shrinking, especially during summer. Snow cover over land in the Arctic has decreased, notably in spring, and glaciers in Alaska, Greenland, and northern Canada are retreating. According to the Arctic Report Card: Update for 2022 and Arctic Report Card: Update for 2023, rising surface temperatures have fueled bigger and more frequent wildfires in high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere since the 1980s. In addition, permafrost in many parts of the Arctic is warming and thawing.

Scientists have already seen evidence of positive feedbacks of warming in the Arctic. As permafrost thaws, frozen peat decays. As peat decays, carbon dioxide and methane are released back into the atmosphere, further contributing to warming. According to the 2019 Arctic Report Card, permafrost thaw throughout the Arctic may be releasing an estimated 300 to 600 million tons of net carbon per year to Earth's atmosphere.

The changing vegetation of the Arctic also affects the surface brightness, which then influences warming. As the Arctic atmosphere warms, it can hold more water vapor, which is an important greenhouse gas. The loss of ice mass from the Greenland Ice Sheet is increasing to such an extent that sea level rise forecasts have had to be adjusted.

There are also negative feedbacks in the Arctic. For instance, higher temperatures may allow for a longer Arctic growing season, allowing plants to grow longer and take up more carbon from the air. However, most evidence suggests that the positive feedback effects outweigh the negative feedbacks.

In Antarctica

The Antarctic Peninsula, a swirly tail of mountains that stretches out from the continent, is one of the fastest warming areas on Earth. Antarctica is covered by an ice sheet roughly the size of the United States and Mexico combined. The ice sheet is responding to climate change in a variety of ways.

The Transantarctic Mountains divide Antarctica into two sections: East and West Antarctica—indicating regions that lie mostly in the Eastern or Western Hemisphere, respectively. Though research has shown that climate change has impacted both sides, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) is of particular concern because its underlying bedrock rests far below sea level. Ice shelves buttress the continental ice sheet, putting the brakes on glacial flow into the oceans. Warming ocean waters are cutting under the floating ice shelves and eroding the point of its connection to land. Coupled with higher air temperatures, the ice shelves could rapidly crumble. Since much of the WAIS bedrock is well below sea level, as the ice sheet begins to retreat and thin, a large portion of the ice sheet may lift off the bedrock and float. The floating ice provides less resistance to flow, and the large ice mass will slide faster into the ocean, causing further thinning, retreat, and flotation—a potentially runaway process that could increase sea level at several times the current rate.

Antarctica contains more than half of the world's fresh water in its ice sheet. If the WAIS portion crumbled into the ocean, it would raise sea levels by 3.5 meters (12 feet) and affect ocean currents as it flushed fresh water into the briny ocean. When sea levels rise, they do not rise uniformly: winds and Earth’s gravity distribute water unevenly. Some coastal areas will be inundated by higher-than-average sea level increases, while others less so.