By Michon Scott

Sea ice melt is not a significant contributor to sea level rise, but its contribution is not nothing, either. Sea ice is composed mostly of fresh water, which is less dense than salty ocean water. Consequently, sea ice melt produces water that takes up more volume than an equivalent weight of salt water, although the difference is minimal.

Ocean warming and land ice melt have a much greater impact on global sea level than sea ice melt. Still, sea ice is worth monitoring closely because of correlation; the same higher temperatures that can drive sea ice decline can also raise sea level.

Like ice cubes in your glass—up to a point

Historically, sea ice melt’s contribution to sea level rise has been largely ignored. The often-used example says that ice cubes melting in your drink do not raise the liquid level in your glass. This is true for just about any beverage you might consume, but you probably never drink iced salt water.

Ice floating in liquid displaces its own weight. That does not necessarily mean the floating ice displaces its own volume. The effect of the ice melt depends on the composition of the ice and the composition of the liquid in which it floats, and the presence or absence of salt makes a difference.

Salt does not freeze the way water does. When ocean water freezes and forms sea ice, it expels its salt content. The process does not happen overnight, at least not completely. Relatively new sea ice often retains some salt in brine pockets. Given enough time, however, the ice expels nearly all its salt. As a result, multiyear ice is composed almost entirely of fresh water. This has implications for ocean level when the ice melts.

Imagine filling two identical buckets, each holding 1 kilogram (roughly 2 pounds) of liquid—fresh water in one bucket and salt water in the other. The fresh water would occupy slightly more space in its bucket compared to its salty companion. The difference would likely be too small to notice with the naked eye. But scale up the amounts to perhaps a metric ton of fresh versus salty water, and the difference, though still small, would be more noticeable.

In 2007, Peter Noerdlinger and Kay Brower published a study examining the effect of floating ice melting in salt water. They found that when freshwater ice melted, the meltwater was 2.6 percent more voluminous than an equivalent weight of salt water. They also concluded that when land ice slides into the ocean, it raises sea level in two phases, first by displacing its own weight and second by adding the additional 2.6 percent when it eventually melts.

Sea ice’s relative importance to ocean level

The implication of Noerdlinger and Brower’s 2007 paper is that sea ice melt gives a small boost to ocean level, but if conditions warmed enough to melt all the world’s floating sea ice, coastal communities would have bigger problems. Namely, thermal expansion of the ocean and the melt of land ice contribute more to sea level.

Thermal expansion refers to the process in which warming water increases in volume. In fact, many substances, not just ocean water, expand in warmer conditions and contract in cooler conditions. Water is also added to the world’s ocean through the melt of ice on land, including glaciers and ice sheets. Together, these processes add up.

Though sea ice melt’s direct impact on sea level is tiny, it can have a significant indirect impact. Sea ice plays an important role in stabilizing the fronts of ice shelves—thick slabs of ice often fed by glaciers that spread over the ocean surface along coastlines. When sea ice retreats, increased wave action can stress an ice shelf and warmer ocean waters can melt the bottom of the shelf. If the ice shelf disintegrates, one or more glaciers feeding that ice shelf can accelerate. This process introduces a new mass of ice into the ocean. (See What happened to the Larsen Ice Shelf? for more information.)

Sea ice loss coincides with other factors

NSIDC’s Sea Ice Index data show declines in sea ice extent (the area of ocean with at least 15 percent sea ice concentration) in the Northern Hemisphere in all months since the start of the satellite record in 1979. In September, the month of the Arctic annual minimum, the decline rate was 12.1 percent per decade from 1979 to 2024. Antarctic sea ice has shown a less clear long-term trend, with substantial year-to-year variability, but a string of low extents starting in 2016 tugged the long-term trend downward. In February, typically the month of the Antarctic minimum, the decline rate was 2.6 percent per decade from 1979 to 2025.

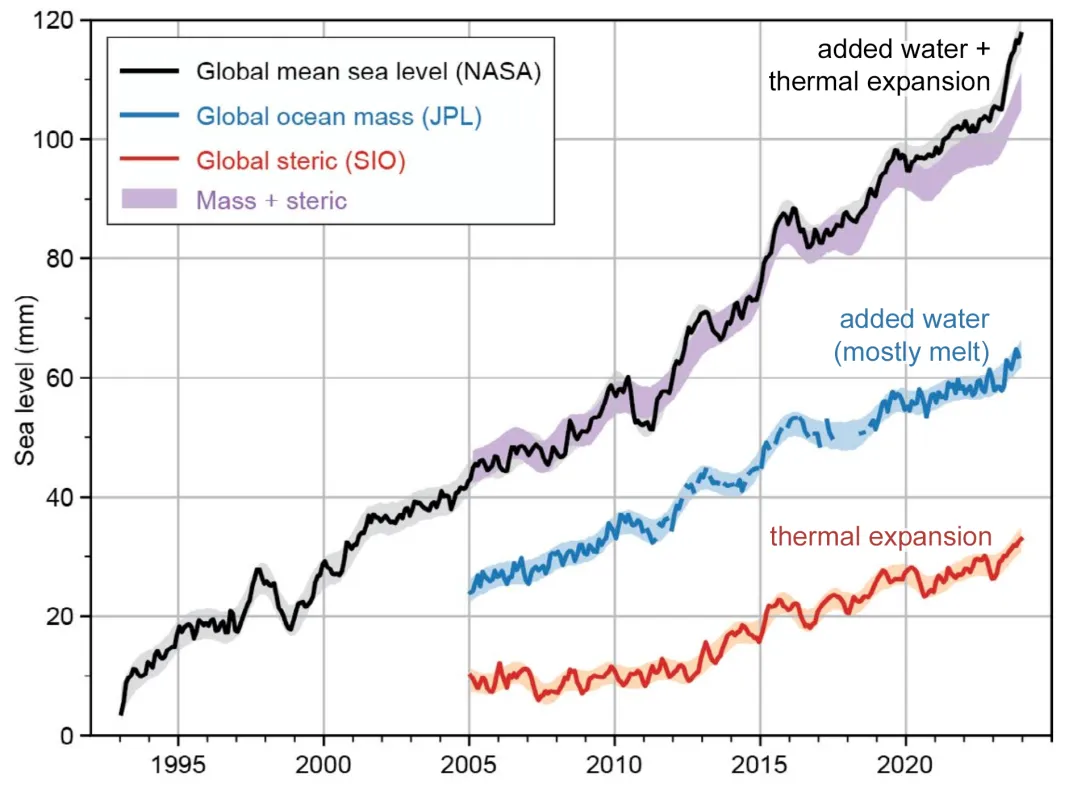

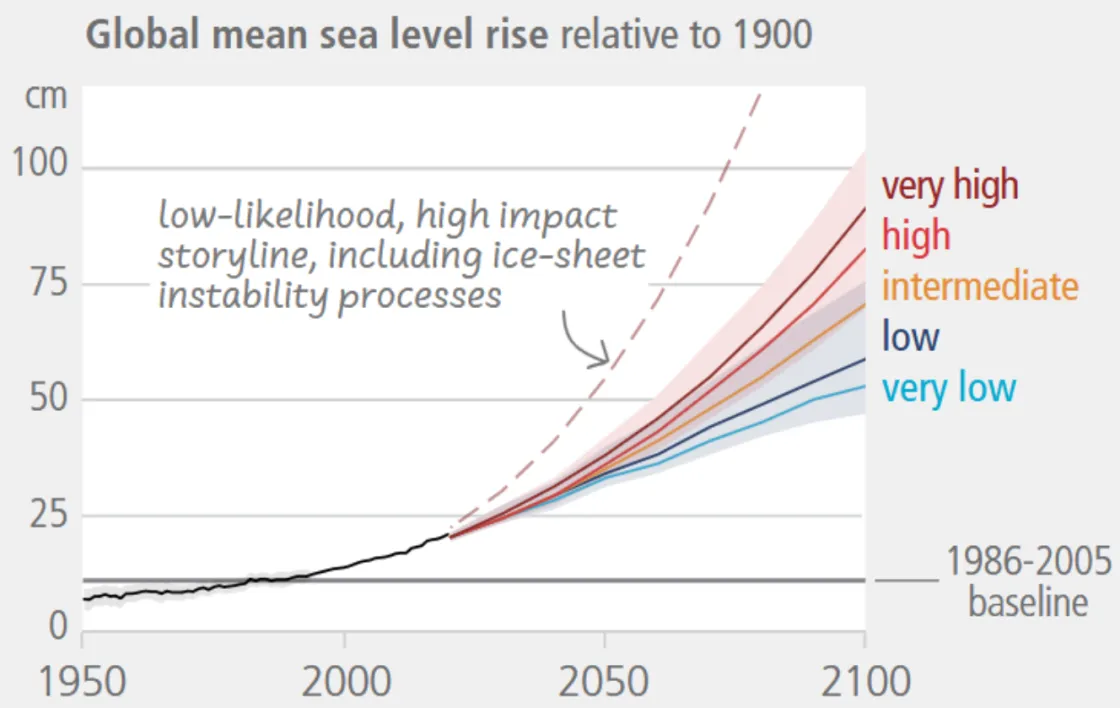

Meanwhile, global mean sea level is rising. The American Meteorological Society’s State of the Climate in 2023 reported that annual mean sea level reached a new high: 101.4 millimeters (3.99 inches) above mean sea level in 1993. Furthermore, the report stated that 2023 was the twelfth consecutive year in which global mean sea level rose relative to the previous year. The report also stated that 28 of the previous 30 years had experienced sea level rise relative to the previous year. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Climate Change in 2023 Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers reported that sea level could be expected to continue rising for hundreds or even thousands of years, but that curbing emissions might mitigate some sea level increases. Sea level rise continued in 2024; a NASA-led analysis published in mid-March 2025 concluded that global sea level rose even faster than expected in 2024: 59 millimeters (0.23 inches).

Remember that correlation does not necessarily mean causation. Sea ice loss does not cause sea level rise beyond the additional roughly 2.6 percent caused by density differences between salt water and fresh water. Still, prolonged sea ice loss indicates that sea level rise could worsen because the same warming pressures drive both sea ice melt and sea level rise.

References

Blunden, J., and T. Boyer, Eds. 2024: State of the Climate in 2023. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 105 (8): Si-S483. doi:10.1175/2024BAMSStateoftheClimate.1.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2023. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. doi:10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001.

Lindsey, R. 2023. Climate change: Global sea level. NOAA Climate.gov. Accessed March 10, 2025.

Noerdlinger, P.D., and K.R. Brower. 2007. The melting of floating ice raises the ocean level. Geophysical Journal International 170(1): 145-150. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03472.x.

Johnson, G.C., R. Lumpkin, M.A. Alexander, D.J. Amaya, B. Beckley, T. Boyer, F. Bringas, B.R. Carter, I. Cetinić, D.P. Chambers, D. Chan, L. Cheng, S. Dong, S. Elipot, R.A. Feely, .A. Franz, Y. Fu, M. Gao, J. Garg, D. Giglio, J. Gilson, M. Goes, G. Graham, B.D. Hamlington, W. Hobbs, Z.-Z. Hu, B. Huang, M. Ishii, M.G. Jacox, A. Jersild, S. Jevrejeva, W.E. Johns, R.E. Killick, M. Kuusela, P. Landschützer, E. Leuliette, C. Liu, R. Locarnini, S.M. Lozier, J.M. Lyman, M.A. Merrifield, A. Mishonov, G.T. Mitchum, B.I. Moat, R.S. Nerem, M. Oe, R.C. Perez, I. Pita, S.G. Purkey, J. Reagan, K. Sato, C. Schmid, D.A. Smeed, R.H. Smith, P.W. Stackhouse Jr., T. Sukianto, W. Sweet, P.R. Thompson, J.A. Triñanes, D.L. Volkov, R. Wanninkhof, R.A. Weller, T.K. Westberry, M.J. Widlansky, J.K. Willis, X. Yin, L. Yu, and H. Zhang. 2024. Global oceans: Sea level variability and change. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 105 (8): S178-S182. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-24-0100.1.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2025. NASA analysis shows unexpected amount of sea level rise in 2024. Accessed March 17, 2025.