By: Audrey Payne

Long before the introduction of weather service forecasts, Inuit read the Arctic sky and environment to predict the weather. As their lands and waters changed over time, Inuit families passed down key knowledge to safely navigate across sea ice and snow, imperative for a culture that travels long distances to hunt and draws its livelihood and identity from a deep relationship with the land.

Kangiqtugaapik (Clyde River), Nunavut, meaning “nice little inlet” in Inuktitut, is an Inuit community of about 1,000 residents on the northeast coast of Baffin Island. The community is located on a flood plain surrounded by high mountains and deep fjords. Accessible only by airplane, and ship in the summer, the region’s snow-capped mountains, glaciers, and icebergs attract tourists from all over the globe. Its cliffs, which are among the tallest in the world, entice rock climbers and base jumpers.

The Clyde River community maintains a strong subsistence harvesting culture, relying on the land and ocean for food, such as seals, narwhal, polar bears, and fish. Weather and ice conditions affect where, when, and what Inuit harvest, but also the region’s topographical features can impede accurate weather predictions. That is why in 2009, Shari Fox of NSIDC, along with hunters, Elders, and research partners in Clyde River, created the Silalirijiit Project, linking Inuit knowledge with climate science and environmental modeling to better understand how weather patterns are changing in the Clyde River area.

The Silalirijiit (‘those who work with weather’) Project

When the Silalirijiit Project began, Fox had already been working together with the community of Clyde River to research environmental change in the area. She had been there for about ten years, living there full-time for six. She had developed deep connections in the community and worked with community members to identify projects that would be benefit residents. One clear need was access to better weather forecasts. As of 2009, the only available weather data were collected from airports, which are few and far between in the territory, and which frequently resulted in inaccurate predictions.

“This project and its data are meant to give Clyde River residents information they need to augment their own detailed knowledge of the environment, so they can make decisions about travelling safely and hunting successfully,” said Fox. “When you’re taking your grandchildren out hunting by boat for example, you need to know what the wind is going to do because it will affect wave height in the ocean and how safe it will be out there.”

Fox worked with local hunters and Elders to develop the project idea, then formed a team with researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder), Colorado State University (CSU), and the US Forest Service (USFS). Together their goal was to increase the community’s access to weather information by funding local weather stations and documenting Inuit knowledge of weather, weather indicators, and weather forecasting. The team brought to life the Silalirijiit Project, which is supported by the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA) at NSIDC.

The team relied heavily on the input of Elders and hunters to find the most useful locations for weather stations in the Clyde River area. “Inuit have intimate, detailed, experience-based knowledge of the weather patterns here,” said Fox. “They understand how the wind blows through the fjords, how snow is distributed, and how that in turn impacts environmental conditions. Their knowledge is critical in deciding where to put weather stations.”

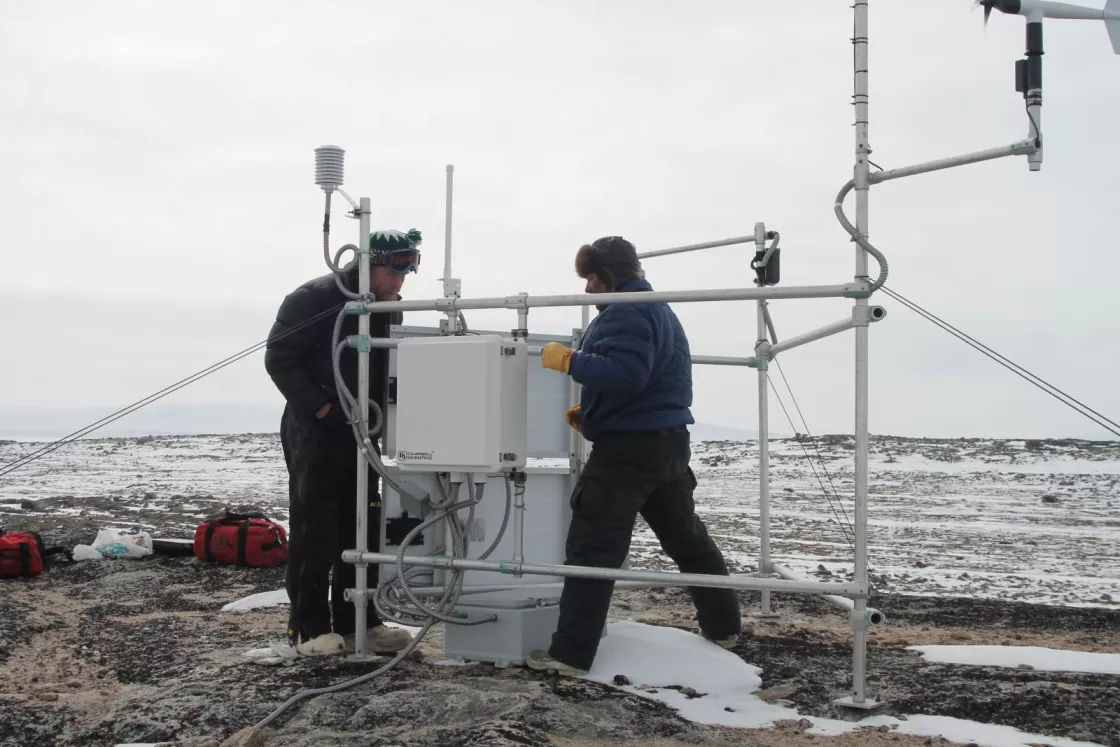

After several meetings and trips in 2009 to confirm the sites, the first weather station was installed in 2010 at Akuliaqattak, about 70 kilometers north of Clyde River. Four weather stations have been installed to date, with the most recent going up this past April and another scheduled for installation next spring. As a result, near-real time data are now available in Inuktitut and English.

An exchange of knowledge

Fox attributes the project’s successes to the strong collaboration amongst team members. The same core project team, which includes core members Fox, Esa Qillaq of Clyde River, Ilkoo Angutikjuak of Clyde River, Glen Liston of CSU, Kelly Elder of USFS, and Henry Huntington of Huntington Consulting, has remained in place for over 10 years and hit only a few snags along the way. Potentially the biggest setback—delayed funding for about two years—was tempered because the community continued station maintenance, and both community and team members chipped in time and funds to bridge the gap.

Esa Qillaq, the project’s weather station technician and expert hunter, continues maintenance on the stations each year, ensuring the skills stay within the community. Each spring, he leads the team to travel four or more hours roundtrip by snowmobile to each station, replacing parts and downloading data.

Thanks to Esa’s leadership, skills, and efforts, the stations have run smoothly, except for one unexpected challenge: damage caused by curious polar bears. On more than one occasion, bears have chewed through essential wiring, taking stations down for periods of time. Fences will not keep the bears out, but increased efforts to keep the stations tidy and the wires out of sight has proven effective; there have not been any further incidents.

Relationship-building has been the most important aspect of the project, Fox said, and while the team consisted of near-strangers 10 years ago, those involved are now close friends. Not only have the southern-based scientists traveled to and stayed in Clyde River, the Clyde River core team and other community members have come to Colorado as well, to learn how the weather data are stored and analyzed, to work as a team in a university setting, and most importantly, to visit the southern-based team’s families and homes to better understand and share in the lives of their counterparts.

The Silalirijiit team uses Google Analytics, which is a tool that analyzes web traffic and number of users, to track if, when, and from where the weather station data are being used, sometimes in unexpected ways. For example, the project website is often accessed just before the weekend and when the forecast predicts storms. The data are accessed regularly by community members, other communities, researchers, educators, and pilots. Community members have told Fox and other team members directly that they value and use the data. In addition, the research team has been able to learn and document what types of weather data are useful to the community and why, and this knowledge guides their science.

The future of the project

Moving forward, the Silalirijiit Project will focus on advancing new types of weather information for the community. For example, Glen Liston and Kelly Elder are using models to identify variables such as wave height and visibility (e.g. blowing snow conditions), that are more useful to hunters than those offered by standard weather station data, such as simply air temperature and humidity. The visiting scientists and Inuit Elders and hunters are working together on these concepts.

The project is also responding to community interest in land-skills training for youth. To support weather knowledge transmission from Elders to youth, a series of Elder-youth science camps will be held over the next three years. The camps will give young Inuit the opportunity to learn weather-related knowledge and skills, and in the process the project will document and understand more about how Inuit weather knowledge is taught and learned in practice.

With the success of the project over the past decade, the Silalirijiit team is eager to see what they can accomplish in the future, together. “It’s really important to all of us on the project team to do research that benefits the community directly,” said Fox. “And we feel like we are able to do that in different ways with this project.”