By Jane Beitler

NSIDC Scientist Ted Scambos had been stuck in a tent on Flask Glacier in Antarctica for nine days when the skies finally broke. A ski-equipped Twin Otter had dropped off Scambos, along with Martin Truffer and Erin Pettit of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and then went back to Rothera Research Station for a second run. But fog rolled in, and the pilots could not risk a second landing. So Scambos, Truffer, and Pettit hunkered down to wait out the bad weather. They now had less than a month to complete their mission and so far, they had not even set up one of the weather and GPS stations they had planned on; had they traveled seven thousand miles to Antarctica in vain? For nine long, boring days the scientists waited in their small tent—unable to go anywhere and without their research gear—but finally, the Twin Otter returned with the rest of the team and the supplies they needed to set up a GPS unit and a super weather station known as an AMIGOS station. After a year of planning, a month of weather delays, and nine days of tense waiting on the ice, the expedition was finally on. They could begin to set up the AMIGOS station to take data that will help researchers understand the effect of rapidly changing climate on vulnerable ice shelves in Antarctica.

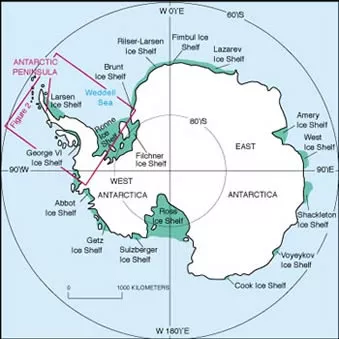

Understanding the Larsen Ice Shelf system

Scambos and NSIDC researchers Terry Haran and Rob Bauer, and Australian electronics consultant Ronald Ross as well as Truffer and Pettit, were in Antarctica to explore the causes and effects of ice shelf breakup. In March 2002, a huge portion of the Larsen B Ice Shelf disintegrated in just a few days. Immediately afterward, glaciers in the affected area began to accelerate. Within a few years, they were moving six to ten times faster, and thinning at an astounding rate (up to 500 feet in 6 years). A small portion of the Larsen Ice Shelf remains, but in recent years it, too, has started to melt, thin, and crack apart. So from December 2009 to March 2010, scientists from several disciplines traveled to the Antarctic Peninsula aboard the Research Vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer, on the NSF-sponsored Larsen Ice Shelf System, Antarctica (LARISSA) expedition. The ship was a base for groups of scientists ranging from biologists to glaciologists to carry out various measurements on the Larsen Ice Shelf. Scambos' team, the glaciology group, aimed to set up instruments on the glaciers that feed into the remaining portion of the Larsen ice shelf. The AMIGOS stations record weather conditions, GPS location, photographs, and other data, and send them back to the researchers via satellite.

Fieldwork in the worst of conditions

Conducting research in Antarctica always carries a risk of weather delays and other problems. The LARISSA expedition this winter was hampered by stormy weather and thicker than usual sea ice. The heavy sea ice prevented the Palmer from reaching its planned destination on the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula, and fog and storms delayed helicopter flights to the planned AMIGOS sites. Scambos and his team were stuck in tents more than once when fog rolled in and trapped them in the field. Towards the end of the mission, the team relocated from the research ship to Rothera, the British research station, to complete the rest of their goals. Despite the bad weather, heavy sea ice, and other delays, the NSIDC team set up three AMIGOS stations, two GPS stations built by UNAVCO, and two seismic stations at key sites on glaciers that flow into the Larsen Ice Shelf. The stations are already sending back data, which will help the researchers understand the dynamics of these glaciers. Scambos hopes that the stations will continue to operate for two to three years. And if, during that time, the last of the Larsen Ice Shelf breaks apart, the researchers will have one-of-a-kind data that will help them figure out how other glaciers in the region will respond to similar events. For more information about the project, visit the LARISSA Project Web site.