By Agnieszka Gautier

“From about the middle of November to the middle of January, the sun doesn’t come up above the horizon,” said Shari Fox Gearheard, a social scientist who lives in the Arctic conducting research for NSIDC. “Around noon we get a little grey for about 45 minutes.”

This is winter in Clyde River, Nunavut, Canada, a small Inuit hamlet on the northeastern shores of Baffin Island. Gearheard has lived here for ten years, working on research projects that bring together Inuit hunters, Elders, youth, and visiting scientists to study climate and environmental change. Traveling in an Arctic winter can be unforgiving. “You don’t want to get lost or stranded,” Gearheard said. “You don’t have the morning, when it’s light again, to say we’ll figure it out then.”

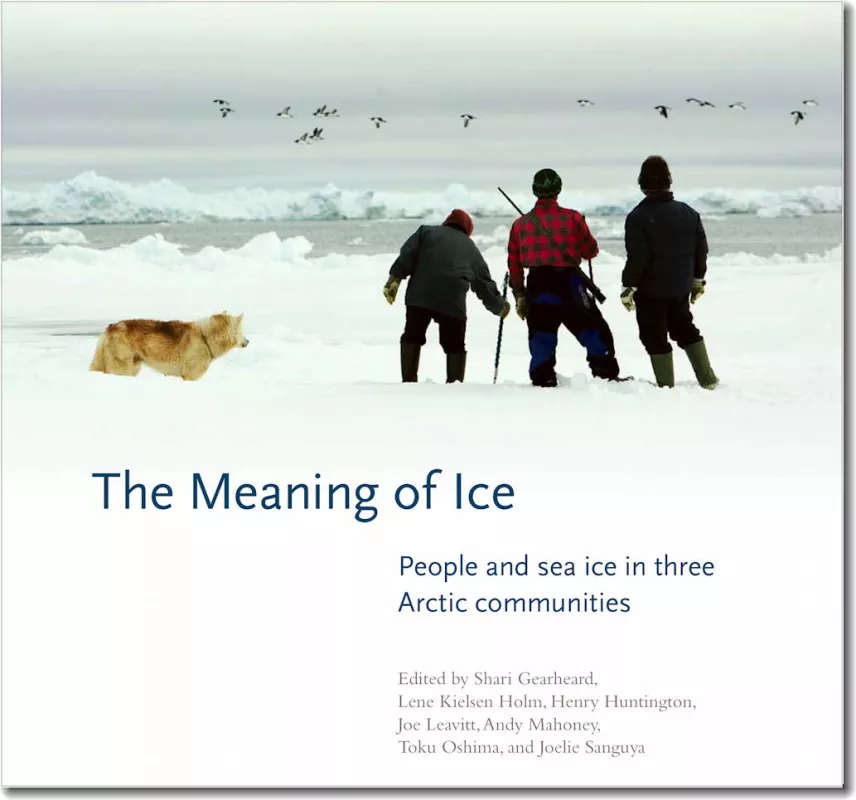

It takes deep knowledge to navigate through these dark winters, and the thinning ice of warming springs. As part of Gearheard’s ongoing collaborative work with Inuit hunters and Elders, she, along with seven other editors, documented Inuit knowledge in a book, The Meaning of Ice: People and Sea Ice in Three Arctic Communities. The book recently won the 2014 William Mills Prize for Non-Fiction Polar Books, awarded by the Polar Libraries Colloquy.

The exchange

Scientists study ice. What is ice? What characteristics does it have? What processes and dynamics? Arctic people understand processes and dynamics, but also find deep meaning in ice. Both forms of knowledge are valid. But in a place of blinding blizzards and wailing winds, the people celebrate ice because it celebrates life. “If you’re from here, your life is tied to sea ice.” Gearheard said. “Sea ice provides for your family, for your community. You are here because of the deep knowledge your ancestors had to not only survive, but thrive from sea ice.”

After all these years of living daily life in the Arctic, Gearheard is still surprised by parts of the book. “A light bulb went on for me: what I see as a kind of ‘Zen of sea ice,’ for lack of a better term. It’s the only way I can think to describe it—to talk about sea ice is to not talk about sea ice.” Sea ice makes its way into every aspect of life. Sea ice is life.

A tome of white

“The book was kind of a surprise,” Gearheard said. “It’s not something we had planned.” Over forty Inuit, Iñupiat, and Inughuit from three different Arctic communities contributed to the book, a product from a five-year National Science Foundation-funded project, called Siku-Inuit-Hila, which translates to Sea Ice-People-Weather in the Inuit language. Though the knowledge exchange of three communities—from Barrow, Alaska; Clyde River, Canada; and Qaanaaq, Greenland—is far-spread, they share a common culture, history, and same language family.

Big and white, the book intends to evoke the Arctic. “It comes to life,” Gearheard said, when asked what she finds exciting about the end result. With glossy pages and striking photographs, drawings, illustrations, and artwork, laid out in lots of white space, it feels much like a coffee table book. “It was never intended to be an academic book,” Gearheard said. But once readers spend time with it, reading the stories and maps, looking at historical photographs, reading recipes, it becomes a true testament to the degree of knowledge Arctic peoples hold about sea ice. “The amount of knowledge shared still blows me away to this day,” Gearheard added. “Everyone has been so generous. The book is packed full of amazing Arctic knowledge.”

Knowledge within

The Meaning of Ice contains four main themes: home, food, freedom, and tools and clothing. Book editor Joelie Sanguya from Clyde River suggested the use of the word freedom. The section is about travel, but for many Arctic communities the sea ice provides a freedom to travel that is not afforded with open waters, especially in Clyde River, where dramatic fjords and mountains restrain travel by land.

In the Arctic, dogs are freedom-bringers as much as ice is. Without trees, only vast open terrain, dog-teaming in a “fan-hitch” allows dogs to choose their own path. Individual lines connect dogs to a sled rather than the familiar image of two-by-two dogs. Each dog is free to feel out what is often blocky and rough sea ice. Dogs can also sense and avoid dangerous or too-thin sea ice. Dogs are respected and appreciated. At the end of journeys, the dogs eat first. As is written in the “Freedom” section, “We need them to stay strong and healthy as our means of transportation. And it is the least we can do to thank them for the work they do for us.”

The section “Tools and clothing” is filled with intricate illustrations from each community such as how to make sealskin parkas and caribou clothing for women. Everything in here, one way or another, is really about sea ice. The way women’s clothing is engineered to carry a baby, to keep it completely warm, to have places to pack diapers, and to be able to move it from back to front to breast-feed without ever exposing it the extreme cold, says more than this “clothing keeps me warm.” “They’re really telling you about their life with sea ice,” Gearheard said. “This book was an opportunity to really explore how meaningful ice is to people who are originally from here and all the ways ice gives meaning,” Gearheard said. “It’s a book with knowledge from three Arctic communities, but the message, about the real meaning of ice, is a global one, a message needed now more than ever as the Arctic faces new challenges and changes.”

References

Fox Gearheard, Shari and L. Kielsen Holm, H. Huntington, J. Mello Leavitt, A. R. Mahoney, M. Opie, T. Oshima, J. Sanguya, eds. The Meaning of Ice: People and sea ice in three Arctic communities. Hanover, New Hampshire: International Polar Institute Press, 2013. Print. For more information on the book: International Polar Institute Press