Yes, satellite sensors sometimes observe sea ice in locations where there is no ice. This problem most often arises along rivers and near coastlines, and it results from limitations in sensor resolution.

Ups and downs of passive microwave

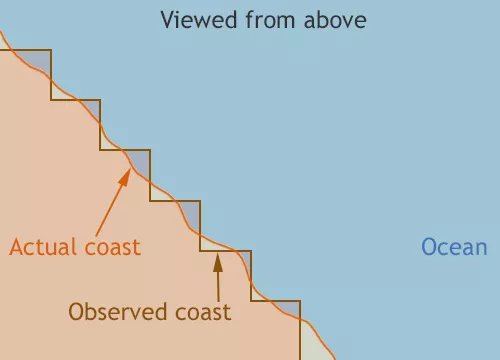

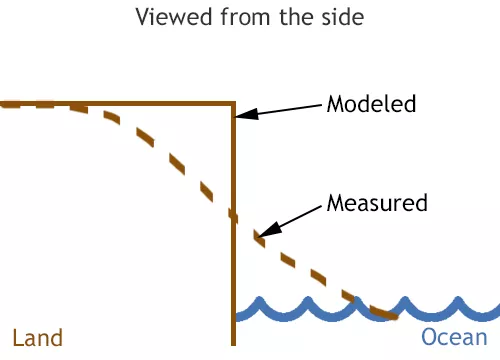

NSIDC relies on passive microwave data to compile sea ice maps. Passive microwave sensors have the advantage of being able to see through the Arctic’s cloudy weather and capture surface data even during long, dark winters, making them ideal for tracking sea ice. The disadvantage, however, is that passive microwave sensors often have low spatial resolution. The sensors collect data in “footprints” that are up to 50 to 70 kilometers (31 to 44 miles) in diameter. Out on the open ocean, for instance, most of these large footprints include only water; inland, most include only land. But along the coasts, footprints often contain both land and water.

“The main issue tends to be land spillover,” said NSIDC scientist Walt Meier. “The land ends at a definitive location, and in our daily maps we mark an area as land or not-land. So there is a discrete boundary. However, the sensor measures areas that include some land and some ocean.”

Is it water? Is it land?

It would be very time-consuming, if not impossible for scientists to pore over the multitude of individual coastal images to determine whether they are mostly land or mostly water. So, they develop algorithms to help classify when the sensor sees land or water, and then further distinguish between water and sea ice.

Meier said, “We measure concentration, which detects the fraction of sea ice, with the rest as water. So the mix between sea ice and ocean is accounted for in the data.” That is not entirely foolproof, however. Meier continued, “Unless the boundary between land and ocean falls almost right along the boundary of those footprints, the sensor will see a mixture of ocean and land. That sometimes fools the algorithm into thinking there is sea ice present.”

If the sensor detects 15 percent ice in an area, it is considered to be ice covered. This is why readers who live along rivers or near coasts occasionally see open water in places where our maps show sea ice. Scientists alleviate these discrepancies by applying masks to the data, which help define land edges so that sea ice does not appear inland, and also help screen out sea ice that is far from the ice edges.

NSIDC updates and applies masks on a monthly basis. Meier said, “For example, the ice that was previously seen along the coast of the Gulf of St. Lawrence is now gone in the July images, because we switched to a new mask.”

Meier and other scientists can also use high-resolution sensors when they need to zoom in and verify where sea ice is—or is not. One of these options is the Multisensor Analyzed Sea Ice Extent (MASIE) project, which includes data with resolution as fine as 4 square kilometers (1.5 square miles). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) supports the project. “For knowing where there is ice now in specific locations, it is a more useful resource than passive microwave,” said Meier. However, because MASIE includes a mix of sources and is subject to human analysis, it does not provide the consistent record that passive microwave sensors do.

Small amounts of sea ice sometimes still appear in unrealistic places in the passive microwave data that NSIDC uses to compile the Daily Sea Ice Extent images shown in the Sea Ice Today. Those errors are small and do not significantly affect the overall estimates of Arctic sea ice extent. The passive microwave data record remains valuable because it has generated a consistent time series since 1979, providing scientists with a long-term view of sea ice that higher-resolution satellites cannot yet offer.

Passive microwave data products at NSIDC

Products used to produce NSIDC’s Sea Ice Index:

- Near-Real-Time DMSP SSMIS Daily Polar Gridded Sea Ice Concentrations

- Sea Ice Concentrations from Nimbus-7 SMMR and DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS Passive Microwave Data

Other frequently used passive microwave products at NSIDC:

- Bootstrap Sea Ice Concentrations from Nimbus-7 SMMR and DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS

- NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration

- AMSR-E/AMSR2 Unified L3 Daily 12.5 km Brightness Temperatures, Sea Ice Concentration, Motion & Snow Depth Polar Grids