The seasonal decline of Arctic sea ice extent proceeded at a near-average pace in May. Extent did not approach record lows but remained well below the 1981 to 2010 average. Sea ice extent was notably below average in the Barents and Chukchi Seas, but less so than in recent years. Western Russia and the central Arctic Ocean were unusually warm. Recent research demonstrates a strong link between the persistently positive Arctic Oscillation of last winter and early spring and the record stratospheric Arctic ozone hole. The Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) ice floe is breaking up and a new one will most likely have to be found to continue the scientific expedition.

Overview of conditions

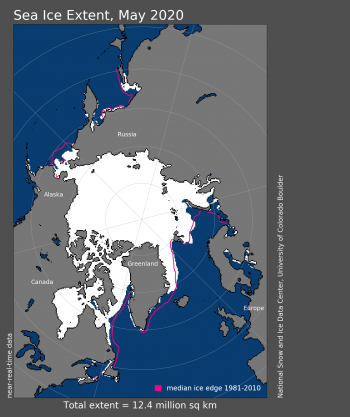

Figure 1. Arctic sea ice extent for May 2020 was 12.36 million square kilometers (4.77 million square miles). The magenta line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that month. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Sea ice extent averaged for May 2020 was 12.36 million square kilometers (4.77 million square miles), placing it in the fourth lowest extent in the satellite record for the month. This was 930,000 square kilometers (359,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 May average and 440,000 square kilometers (170,000 square miles) above the record low mark for May set in 2016. Ice retreat was predominantly in the Bering, Chukchi, Barents and Kara Seas, whereas more modest retreats prevailed in Baffin Bay/Davis Strait, northern Hudson Bay, and the southeastern Greenland Sea. The North Water Polynya also opened up during May. As May came to a close, the ice extent was below average in the Barents and Chukchi Seas, but less so than in recent years. Areas of low extent also included southeastern Greenland, northern Hudson Bay, and northern Baffin Bay. Several coastal polynyas began opening along the Russian coast, a pattern which has been common in recent years. A somewhat larger-than-average opening north of Svalbard appeared in May.

Conditions in context

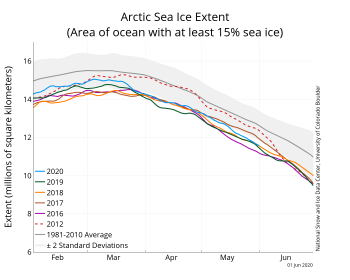

Figure 2a. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of June 1, 2020, along with daily ice extent data for four previous years and the record low year. 2020 is shown in blue, 2019 in green, 2018 in orange, 2017 in brown, 2016 in purple, and 2012 in dashed red. The 1981 to 2010 median is in dark gray. The gray areas around the median line show the interquartile and interdecile ranges of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

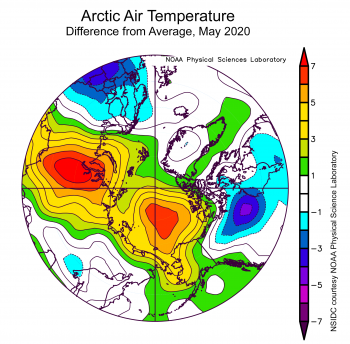

Figure 2b. This plot shows the departure from average air temperature in the Arctic at the 925 hPa level, in degrees Celsius, for May 2020. Yellows and reds indicate higher than average temperatures; blues and purples indicate lower than average temperatures.

Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division

High-resolution image

Through the month, sea ice declined by an average of 54,100 square kilometers (20,900 square miles) per day, slightly faster than the 1981 to 2010 average of 47,000 square kilometers (18,000 square miles) per day. The total sea ice loss during May 2020 was 1.68 million square kilometers (649,000 square miles).

Air temperatures at the 925 hPa level (about 2,500 feet above the surface) were above average over almost all of the Arctic Ocean, with departures as much as 7 degrees Celsius (13 degrees Fahrenheit) over the central Arctic Ocean (Figure 2b). Temperatures were also up 7 degrees Celsius (13 degrees Fahrenheit) over the western portion of Russia. Far northern Canada had temperatures on the order of 3 to 5 degrees Celsius (5 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) below average.

Sea level pressures were especially low over Scandinavia, driving winds from south to north toward the Ob River estuary and Kara Sea region was unusually warm. Pressures were quite high over the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

May 2020 compared to previous years

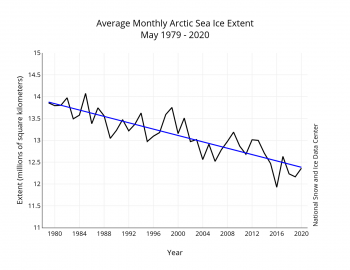

Figure 3. Monthly May ice extent for 1979 to 2020 shows a decline of 2.7 percent per decade.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Including 2020, the linear rate of decline for May sea ice extent is 2.7 percent per decade. This corresponds to a trend of 36,400 square kilometers (14,100 square miles) per year, or about the size of the state of Indiana. Over the 42-year satellite record, the Arctic has lost about 1.36 million square kilometers (525,000 square miles) of ice in May, based on the difference in linear trend values in 2019 and 1979. This is comparable to about twice the size of the state of Alaska.

Arctic ozone hole and Arctic Oscillation

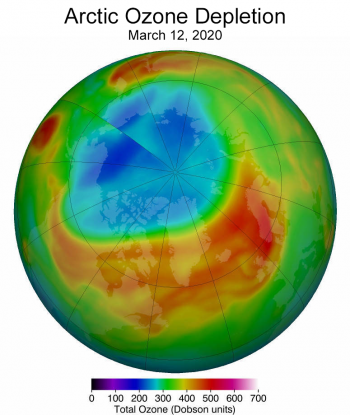

Figure 4. Arctic stratospheric ozone reached its record low level of 205 Dobson units, shown in blue and turquoise, on March 12, 2020.

Credit: NASA

High-resolution image

As noted in our previous post, the Arctic Oscillation (AO), a key pattern of atmospheric variability over the Arctic and northern Atlantic, was in a persistently positive (cyclonic) phase from mid-December through early spring. Such persistence, which ended only in early May, is highly unusual, and appears to be linked to a strong, cold stratospheric polar vortex and the largest Arctic stratospheric ozone hole observed to date (Figure 4). Scientists have learned there are two-way relationships—what happens in the stratosphere (high in the atmosphere) influences what happens in the lower atmosphere (the troposphere), and vice versa. A study by University of Colorado researcher Zac Lawrence and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) researchers Judith Perlwitz and Amy Butler, submitted recently to the Journal of Geophysical Research, took a close look at these connections. They find that the winter of 2019 to 2020 featured an exceptionally strong and cold stratospheric polar vortex. In general, atmospheric waves generated in the troposphere spread both outward and upward into the stratosphere where they can disturb and weaken the stratospheric polar vortex. But this wave activity was fairly weak this past winter, so the vortex remained largely undisturbed. The vortex was also configured in a way such that upward propagating waves were “reflected” back downwards, which further enabled the vortex to remain strong and cold. The end result is that the cyclonic (counterclockwise) circulation at the surface associated with the positive AO was tied closely to the cyclonic circulation of the strong, cold stratospheric vortex. The cold conditions in the stratosphere and its persistence into spring in turn provided favorable conditions to form polar stratospheric clouds, which foster ozone loss through well-understood chemical processes.

MOSAiC turns into a mosaic

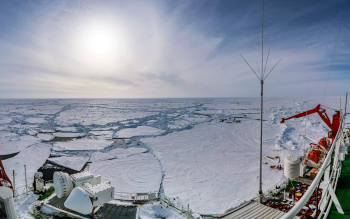

Figure 5a. Before the RV Polarstern left its ice floe location to exchange crew and scientists for the next leg of the MOSAiC (Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate) expedition, ice break ups around the ship intensified.

Credit: C. Rohleder

High-resolution image

Figure 5b. A tent compresses under the pressure of Arctic sea ice ridging, showing increased instability in the region surrounding the RV Polarstern. Surface melt appears at the forefront of the image.

Credit: J. Schaffer

High-resolution image

Scientists on leg three of the Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) expedition left their ice floe, which was specifically selected for having survived one summer melt season, on May 16 to exchange crew and scientists and pick up cargo from transport vessels in Svalbard. Before the RV Polarstern ship actually departed, scientists hoped to leave behind several instruments that began monitoring ice, ocean, and atmospheric conditions back in October 2019 when the Central Observatory around the ship was initially established. Some of these instruments included autonomous light stations that measure the amount of light under the ice and changes in water color caused by phytoplankton growth. However, as the scientists were getting ready to leave, the ice floe began to break apart, rendering the MOSAiC floe into a true mosaic of ice blocks (Figure 5a and 5b). With such unstable conditions, all of the instrumentation used to provide calibration and validation data for overflights of satellites and aircraft were removed temporarily. It is not clear how many of the instruments left behind will survive, including the light stations. The warming and power hut from the remote sensing site, for instance, was left on the ice and was in a precarious situation as cracks in the ice opened nearby. In more recent days, images from cameras left behind indicate that the surface is melting which will likely make the floe more unstable. Given these conditions, it remains unclear whether or not the MOSAiC expedition will need to find a new floe to continue the experiment through September 2020.

Effects of cyclones on sea ice

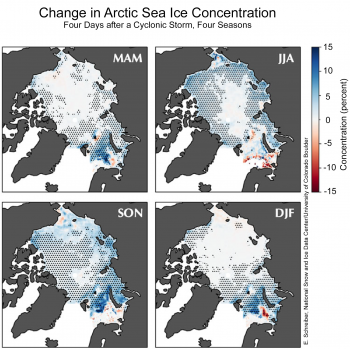

Figure 6. These maps of the Arctic Ocean compare sea ice concentration changes four days after cyclonic storms were present to changes that occur when no storms are present. MAM stands for March-April-May; JJA stands for June-July-August; SON is September-October-November; and DJF is December-January-February. Blue tint indicates greater sea ice concentration after a cyclone; the dots indicate areas where the change is different than random variations in sea ice conditions.

Credit: E. Schreiber, University of Colorado Boulder

High-resolution image

A recently-published study by University of Colorado Boulder doctoral candidate Erika Schreiber considered the effects of the passage of Arctic low pressure systems (extratropical cyclones) on sea ice concentration. In earlier studies, a range of effects has been attributed to storms. Some point to increasing sea ice concentration locally, while others argue that winds associated with cyclones disperse the ice. Schreiber’s research shows that, overall, the thermodynamic effects (cold air, snow, and cloudiness) associated with storms increase sea ice concentration in impacted areas days after the storm hit (Figure 6). In warm months, cyclones slow down melt, while in cold months they tend to speed up freezing. The effects are greatest in summer and autumn, when the ice pack is already changing rapidly, but do still occur along the ice margin in spring and winter. The result has implications for short- and medium-term forecasting of sea ice conditions.

Further reading

Schreiber, E. A. P. and M. C. Serreze. 2020. Impacts of synoptic-scale cyclones on Arctic sea ice concentration: a systematic analysis. Annals of Glaciology, 1–15. doi:10.1017/aog.2020.23.