January of 2018 began and ended with satellite-era record lows in Arctic sea ice extent, resulting in a new record low for the month. Combined with low ice extent in the Antarctic, global sea ice extent is also at a record low.

Overview of conditions

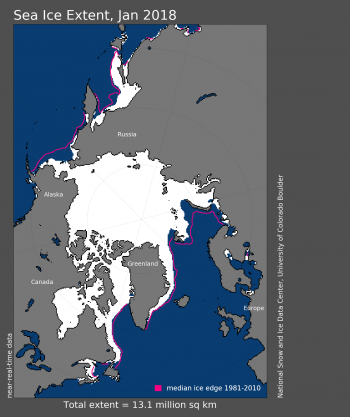

Figure 1. Arctic sea ice extent for January 2018 was 13.06 million square kilometers (5.04 million square miles). The magenta line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that month. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

The new year was heralded by a week of record low daily ice extents, with the January average beating out 2017 for a new record low. Ice grew through the month at near-average rates, and in the middle of the month daily extents were higher than for 2017. However, by the end of January, extent was again tracking below 2017. The monthly average extent of 13.06 million square kilometers (5.04 million square miles) was 1.36 million square kilometers (525,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average, and 110,000 square kilometers (42,500 square miles) below the previous record low monthly average in 2017.

The pattern seen in previous months continued, with below average extent in the Barents and Kara Seas, as well as within the Bering Sea. The ice edge remained nearly constant throughout the month within the Barents Sea, and slightly retreated in the East Greenland Sea. By contrast, extent increased in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, off the coast of Newfoundland, in the eastern Bering Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk. Compared to 2017, at the end of the month, ice was less extensive in the western Bering Sea, the Sea of Okhotsk and north of Svalbard, more extensive in the eastern Bering Sea and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Overall, the Arctic gained 1.42 million square kilometers (548,000 square miles) of ice during January 2018.

Conditions in context

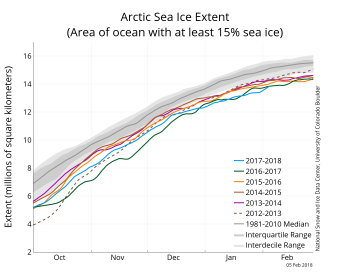

Figure 2a. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of February 5, 2018, along with daily ice extent data for five previous years. 2017 to 2018 is shown in blue, 2016 to 2017 in green, 2015 to 2016 in orange, 2014 to 2015 in brown, 2013 to 2014 in purple, and 2012 to 2013 in dotted brown. The 1981 to 2010 median is in dark gray. The gray areas around the median line show the interquartile and interdecile ranges of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

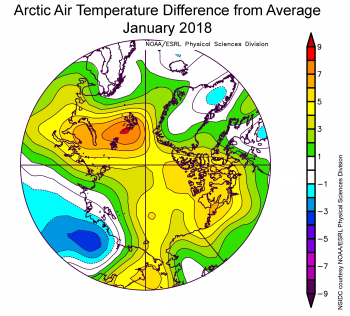

Figure 2b. The plot shows air temperatures in degrees Celsius in the Arctic as difference from average for January 2018. Yellows, oranges, and reds indicate higher than average temperatures; blues and purples indicate lower than average temperatures.

Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division

High-resolution image

Air temperatures at the 925 hPa level (about 2,500 feet above sea level) remained unusually high over the Arctic Ocean (Figure 2b). Nearly all of the region was at least 3 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) or more above average. The largest departures from average of more than 9 degrees Celsius (16 degrees Fahrenheit) were over the Kara and Barents Seas, centered near Svalbard. On the Pacific side, air temperatures were about 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) above average. By contrast, 925 hPa temperatures over Siberia were up to 4 degrees Celsius (7 degrees Fahrenheit) below average. The warmth over the Arctic Ocean appears to result partly from a pattern of atmospheric circulation bringing in southerly air, and partly from the release of heat into the atmosphere from open water areas. Sea level pressure was higher than average over the central Arctic Ocean, stretching towards Siberia. This pattern, coupled with below average sea level pressure over the Chukchi and Bering seas, helped to move warm air from Eurasia over the central Arctic Ocean.

Ice growth for January averaged 37,000 square kilometers (14,000 square miles) per day, close to the average rate for the month of 42,700 square kilometers per day (16,486 square miles per day). In the Barents Sea, the ice extent was the second lowest during the satellite data record. Ice conditions in this region of the Arctic are increasingly viewed as important in having downstream effects on atmospheric circulation. These proposed links include northward expansion of the Siberian High and cooling over northern Eurasia.

January 2018 compared to previous years

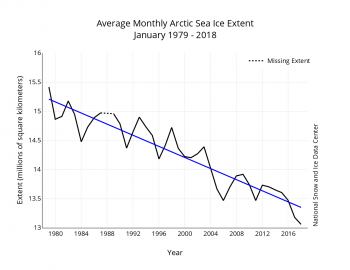

Figure 3. Monthly January ice extent for 1979 to 2018 shows a decline of 3.3 percent per decade.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

The linear rate of decline for January is 47,700 square kilometers (18,400 square miles) per year, or 3.3 percent per decade.

Engaging stakeholders in sea ice forecasting

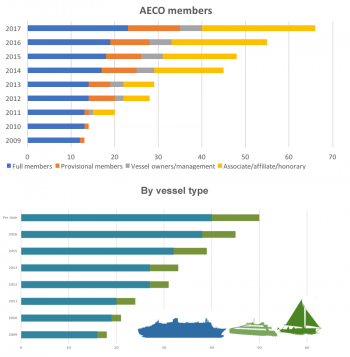

Figure 4. These graphs show changes in polar tourism based on membership in the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO, top), and by the number and type of Arctic vessels operated or managed (bottom).

Credit: Kelvin Murray, Director, Expedition Operations EYOS Expeditions

High-resolution image

Uncertainty about future sea ice conditions presents challenges to industry, policymakers, and planners responsible for economic, safety, and risk mitigation decisions. The ability to accurately forecast the extent and duration of sea ice on different timescales is relevant to a wide range of Arctic maritime activities. While there have been considerable advances in sea ice forecasting over the past decade, it remains unclear how well end users are able to utilize these products and services in their planning. In response, the Sea Ice Prediction Network, in collaboration with several sponsors, held a workshop at the Arctic Frontiers Conference in Tromsø, Norway to foster dialogue between stakeholders and sea ice forecasters.

Conference attendees recognized that the sea ice forecasting community and users of these forecasts need a common language. Often forecast users do not understand the data presented by forecasters, nor do they have the skills to interpret the complex data products. Most marine operators in the Arctic require accurate daily to short-term (< 72 hours) information on the sea ice edge and near-ice-edge concentration. Forecast users often want additional information such as ice strength, ice thickness and ice drift. These data need to be accessed in a user-friendly format that can be easily downloaded (e.g., to a ship at sea). Typically, ice charts from national ice centers or high-resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar image maps are used for describing and analyzing sea ice for real-time navigation.

Longer-term seasonal ice forecasts are potentially useful to the polar marine industry but are not yet being relied upon. While improving, the uncertainty in these forecasts has not been clearly communicated. Nevertheless, logistics planners are interested in using longer-term forecasts, mostly to augment or extend more timely data or in-house diagnostics. Tour operators in particular desire seasonal and even two- to three-year forecasts so that they can plan what to offer their customers. Along with the increase in polar tourism (Figure 4), there is also significant industry traffic in the European Arctic, the Northwest Passage and some areas in the Northern Sea Route. Due to the decreasing ice cover, we can expect an extension of the seasonal activity, with ships embarking earlier and ending their journeys later than in previous years. This underscores the need for accurate forecasting, extending to the more variable shoulder seasons of Arctic sea ice.

Importance of ice drift

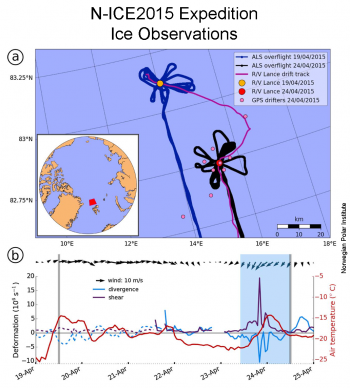

Figure 5. The top figure shows the location of the R/V Lance during the N-ICE2015 expedition (pink lines) with aircraft flight lines shown in black and blue. The bottom figure shows a time series of wind speed and direction, together with rates of ice divergence (blue line) and shear (purple line). Figure from Itkin et al. 2017.

Credit: Norwegian Polar Institute

High-resolution image

As the Arctic sea ice cover continues to thin, convergent sea ice motion can more readily pile up ice into large ridges. Such ridges can be hazardous to marine activities in the Arctic. Divergent ice motion produces openings in the ice called leads, where new ice can readily grow. Winds are the main driver for both ridging and lead formation. A single storm event can lead to significant redistribution of sea ice mass through ridging and new leads. As part of the Norwegian Young Sea ICE (N-ICE2015) expedition, colleagues at the Norwegian Polar Institute made detailed sea ice thickness and ice drift observations before and after a storm in an area north of Svalbard (Figure 5). Results showed that about 1.3 percent of the level sea ice volume was pressed together into ridges. Combined with new ice formation in leads, the overall ice volume increased by 0.5 percent. While this is a small number, sea ice in the North Atlantic is typically impacted by 10 to 20 storms each winter, which could account for 5 to 10 percent of ice volume each year.

Antarctic sea ice also low, leading to low global sea ice extent

In the Southern Hemisphere, after January 11 sea ice began tracking low, leading to a January average extent that was the second lowest on record. The lowest extent for this time of year was in 2017. Extent is below average in the Ross Sea and the West Amundsen Seas, while elsewhere extent remains close to average. The low ice extent is puzzling, given that air temperatures at the 925 hPa level are near average or below average (relative to the 1981 to 2010 period) over much of the Southern Ocean. The Weddell and Amundsen Seas were 1 to 2 degrees Celsius (2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit) below average. Slightly above-average temperatures were the rule in the northwestern Ross Sea.

Further reading

Itkin, P., Spreen, G., Hvidegaard, S. M., Skourup, H., Wilkinson, J., Gerland, S., & Granskog, M. A. 2018. Contribution of deformation to sea ice mass balance: A case study from an N-ICE2015 storm. Geophysical Research Letters, 45. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL076056.