Sea ice declined at a near average rate through the first half of July as low sea level pressure dominated the Arctic Ocean. Wind patterns caused smoke from Siberian forest fires to sweep over the ice.

Overview of conditions

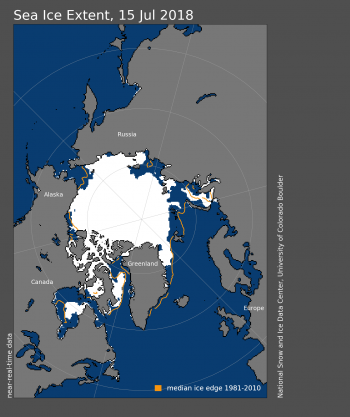

Figure 1. Arctic sea ice extent for July 15, 2018 was 8.5 million square kilometers (3.3 million square miles). The orange line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that day. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

As of July 15, Arctic sea ice extent was 8.5 million square kilometers (3.3 million square miles). This is 1.24 million square kilometers (479,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average, but 670,000 square kilometers (259,000 square miles) above the record low for this day in 2011. While total Arctic sea ice extent was tracking at record low levels during winter, the rate of summer ice loss has been unremarkable thus far. Thus far in July, ice retreat has been most pronounced in the Kara Sea, whereas in the Beaufort Sea, the ice edge expanded slightly southwards. The ice edge has changed little within the Barents and East Greenland Seas on the Atlantic side, and retreat has been sluggish in the Chukchi Sea on the Pacific side of the Arctic Ocean.

Conditions in context

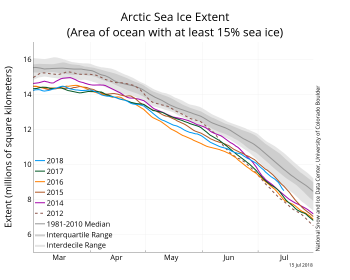

Figure 2a. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of July 15, 2018, along with daily ice extent data for four previous years and the record low year. 2018 is shown in blue, 2017 in green, 2016 in orange, 2015 in brown, 2014 in purple, and 2012 in dotted brown. The 1981 to 2010 median is in dark gray. The gray areas around the median line show the interquartile and interdecile ranges of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

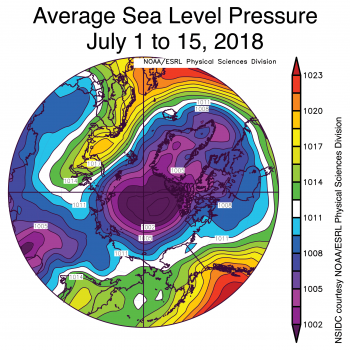

Figure 2b. This plot shows average sea level pressure in the Arctic, in millibars, for July 1 to 15, 2018. Yellows and reds indicate higher than average sea level pressure; blues and purples indicate lower than average sea level pressure.

Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division

High-resolution image

Through the first two weeks of July, ice extent declined at a rate of 134,000 square kilometers (52,000 square miles) per day, which is near the 1981 to 2010 average. The spatial pattern of ice loss has not changed much since the end of June, with minimal ice loss around the entire ice edge. The Beaufort Sea saw some increase in extent due to the transport of ice from the north. Low sea level pressure dominated the central Arctic Ocean and Greenland. Typically, this pattern, associated with counterclockwise (cyclonic) winds is associated with cool conditions and also causes ice divergence, helping to spread the ice cover over a larger area. However, air temperatures over the pole and the East Siberian and Chukchi Seas at the 925 hPa level (approximately 2,500 feet above the surface) ranged 1 to 2 degrees Celsius (2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit) above average for the first part of July. Regions with below average air temperatures were found in the Kara, Laptev, and Beaufort Seas (-1 to -3 degrees Celsius or -2 to -5 degrees Fahrenheit below average).

The passive microwave data show a decrease in ice concentration in several areas of the Arctic Ocean, particularly in northern areas of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. This is not necessarily a real decrease—it manifests as surface melt and the development of melt ponds on the ice surface. Microwave emission is sensitive to the freeze-thaw state of water. Liquid water atop the ice surface changes the returned signal, mimicking a reduced sea ice concentration. Because the calculation of ice extent does not consider concentration (except for the 15 percent concentration threshold), extent values are much less sensitive to this melt effect. During the melt season, ice extent provides a more consistent and reliable measure of total ice cover.

Siberian smoke over the Arctic Ocean

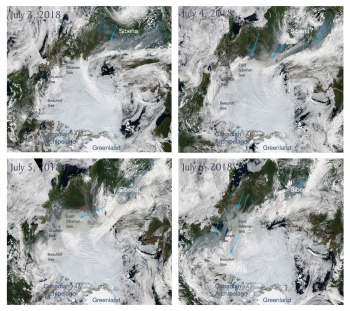

Figure 3. These images from the NASA Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor show the Arctic Ocean and surrounding land from July 3 to 6, 2018. Blue arrows indicate smoke that had drifted from fires in Siberia.

Credit: NASA

High-resolution image

Fires in the western United States have been much in the news lately. Less noted are significant fires in Siberia. Over several days at the beginning of July, smoke from these fires was brought into the Arctic Ocean by winds associated with the pattern of low pressure in the region. The smoke streamed over the East Siberian, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas and eventually across Alaska into northern Canada.

The smoke has two potential effects on sea ice. First, as it drifts over the ice, the smoke particles scatter solar radiation and reduce how much is received at the surface. This has a cooling effect that will tend to reduce the rate of ice loss. However, smoke particles that settle onto the ice will darken the surface, thus decreasing the reflectivity of the surface, or albedo. This increases the amount of solar energy absorbed by the ice and enhances melt. The atmospheric scattering effect of the smoke is short term and dissipates after the smoke drifts away. The surface albedo effect has a longer-term impact and could serve to enhance melt rates through the summer. The magnitude of the effect will depend on how many smoke particles are deposited on the surface, the albedo of the surface that the particles fall on, and the amount of cloud cover which reduces the incoming sunlight. The biggest effect would be on bright, snow-covered ice. It would be smaller on darker melting ice and melt ponds, and there would be no effect in open water areas.