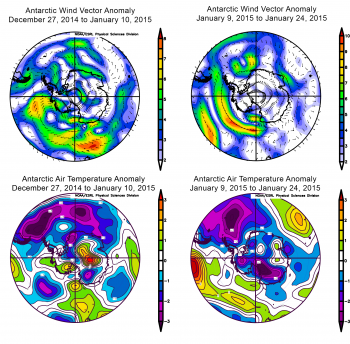

Arctic sea ice extent for June 2015 was the third lowest in the satellite record. June snow cover for the Northern Hemisphere was the second lowest on record. In contrast, Antarctic sea ice extent remained higher than average. The pace of sea ice loss was near average for the month of June, but persistently warm conditions and increased melting late in the month may have set the stage for rapid ice loss in the coming weeks.

Overview of conditions

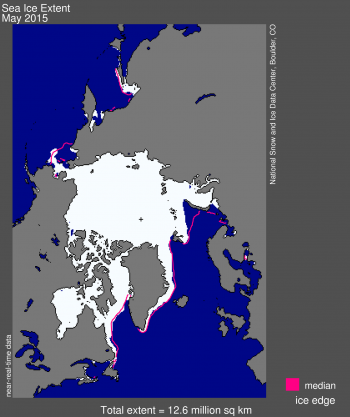

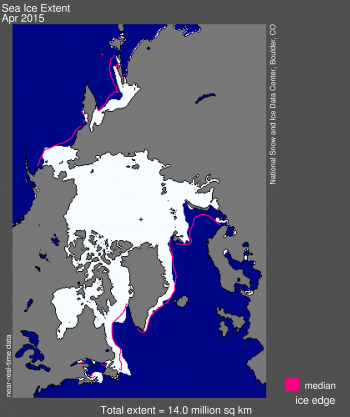

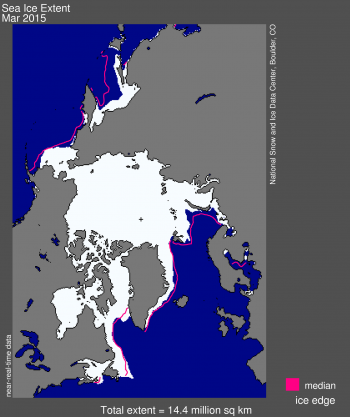

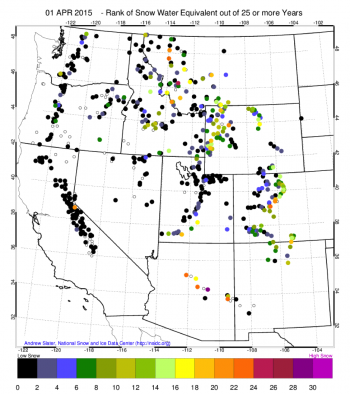

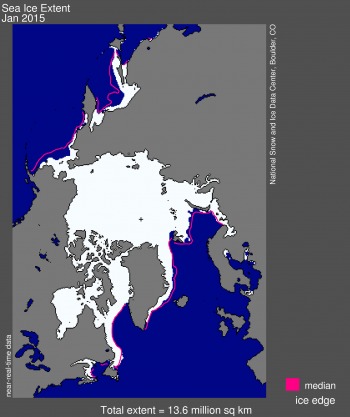

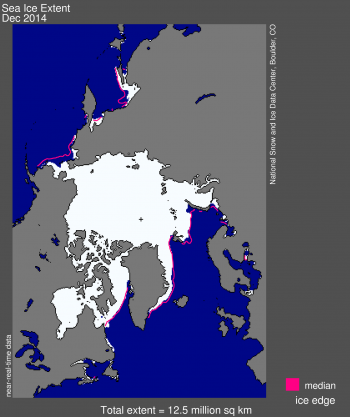

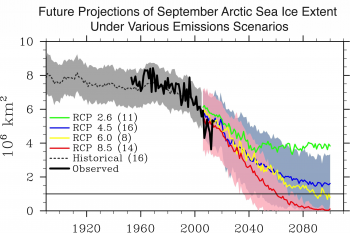

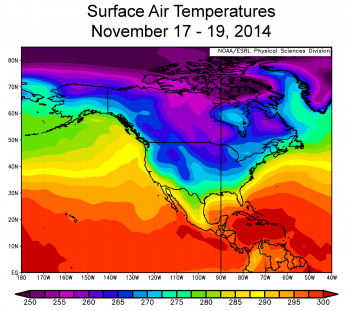

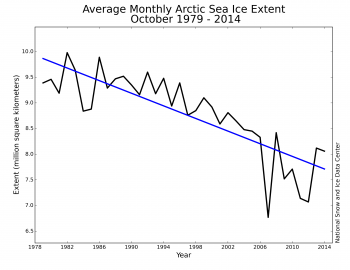

Figure 1. Arctic sea ice extent for June 2015 was 11.0 million square kilometers (4.24 million square miles). The magenta line shows the 1981 to 2010 median extent for that month. The black cross indicates the geographic North Pole. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

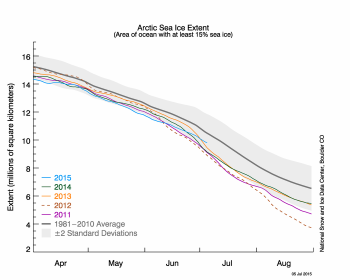

Arctic sea ice extent for June 2015 averaged 11.0 million square kilometers (4.24 million square miles), the third lowest June extent in the satellite record. This is 920,000 square kilometers (355,200 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 long-term average of 11.89 million square kilometers (4.59 million square miles) and 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 square miles) above the record low for the month observed in 2010.

Ice extent remains below average in the Barents Sea as well as in the Chukchi Sea, continuing the pattern seen in May. While extent is below average in western Hudson Bay, it is above average in the eastern part of the bay and near average east of Greenland.

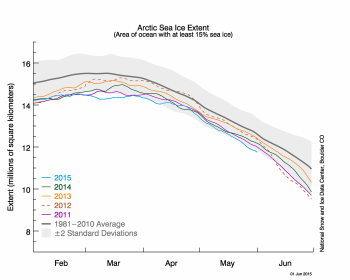

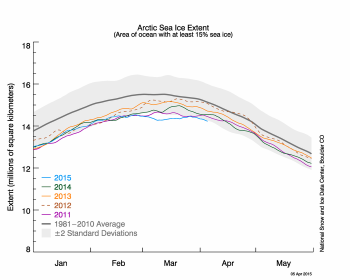

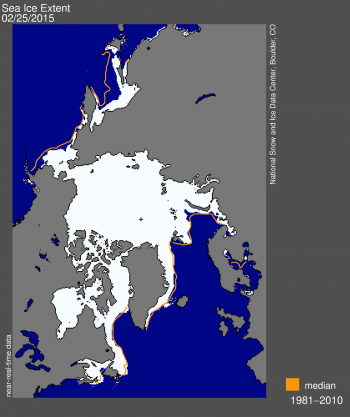

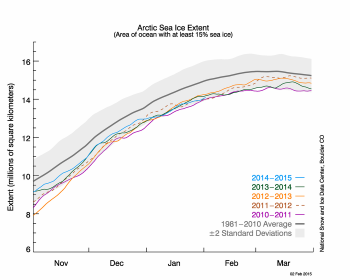

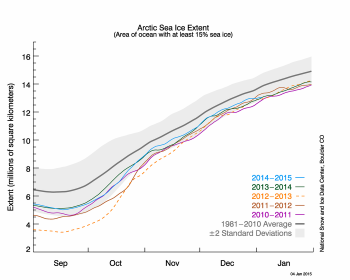

Ice loss typically quickens in June with the largest loss rate occurring in July, the warmest month of the year. A total of 1.61 million square kilometers (622,000 square miles) of ice was lost through the month, slightly slower than the 1981 to 2010 average rate of decline of 1.69 million square kilometers (653,000 square miles). By the end of the month, ice extent for the Arctic tracked within one standard deviation of the 1981 to 2010 average.

Conditions in context

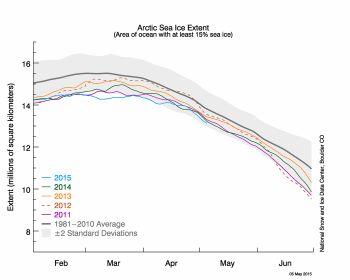

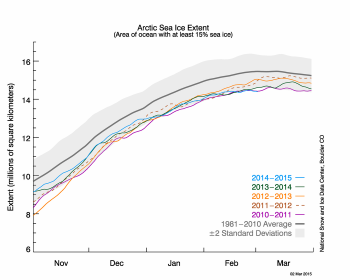

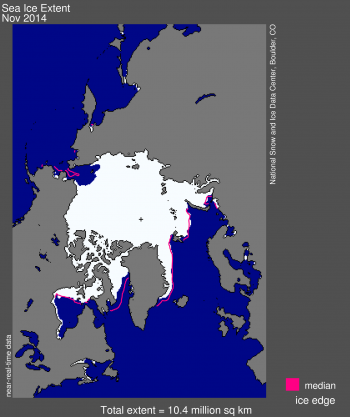

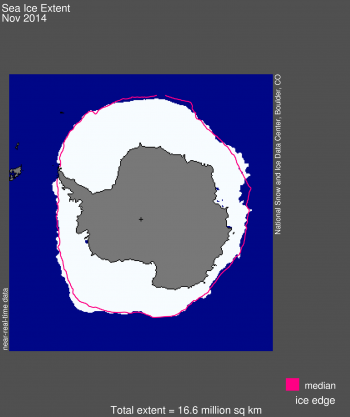

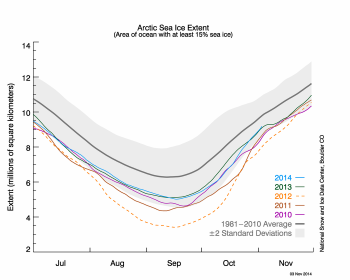

Figure 2a. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of July 5, 2015, along with daily ice extent data for four previous years. 2015 is shown in blue, 2014 in green, 2013 in orange, 2012 in brown, and 2011 in purple. The 1981 to 2010 average is in dark gray. The gray area around the average line shows the two standard deviation range of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

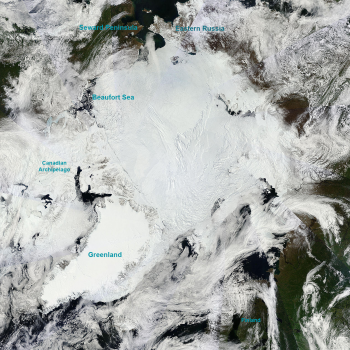

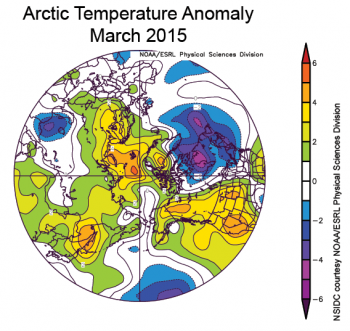

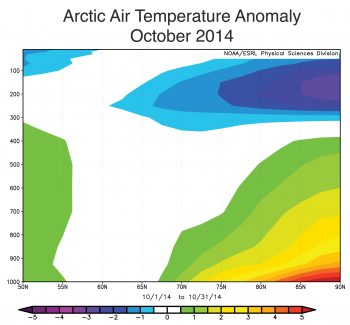

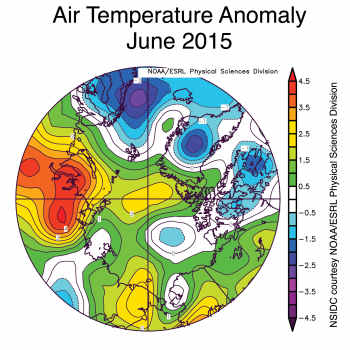

June 2015 was fairly warm in the Arctic. Air temperatures at the 925 millibar level (about 3,000 feet above the surface) were above average over much of the Arctic Ocean, notably in the Kara Sea (2 to 5 degrees Celsius or 4 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit above average) and in the East Siberian Sea (2 to 3 degrees Celsius or 4 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit above average).

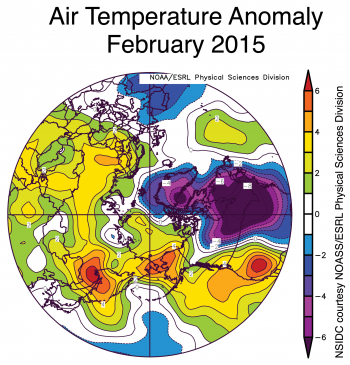

Figure 2b. The plot shows Arctic air temperature anomalies at the 925 hPa level in degrees Celsius for June 2015. Yellows and reds indicate higher than average temperatures; blues and purples indicate lower than average temperatures.

Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division

High-resolution image

The especially warm conditions in the Kara Sea, where ice extent is below average, is consistent with a wind pattern tending to bring in warm air from the south. The wind flows along the northern flank of a low-pressure area centered over the Barents Sea. Northerly winds on the western side of this low-pressure area brought cool conditions to the Norwegian Sea. Temperatures in the northern and eastern Beaufort Sea and much of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago were near or slightly below average.

June 2015 compared to previous years

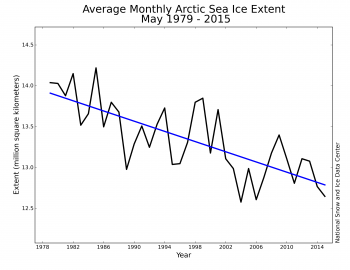

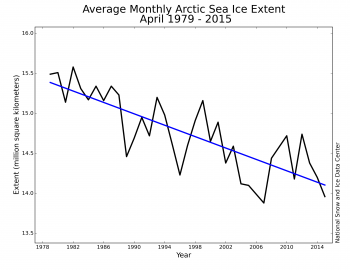

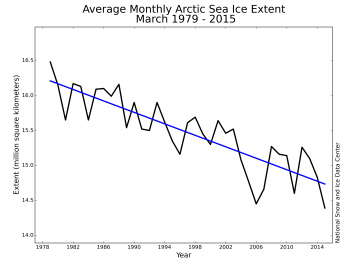

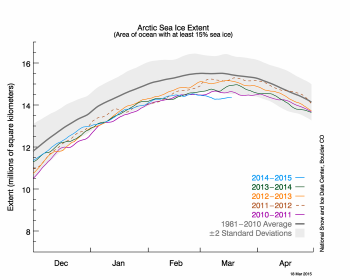

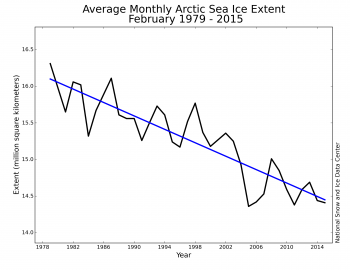

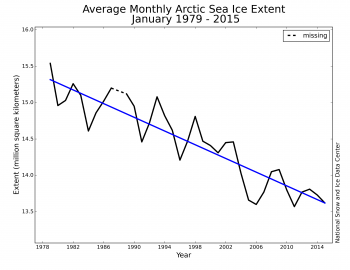

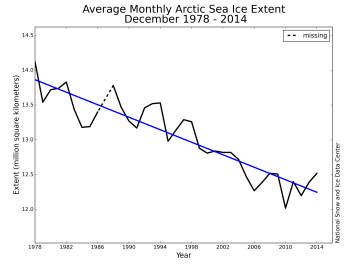

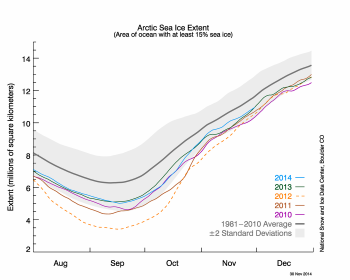

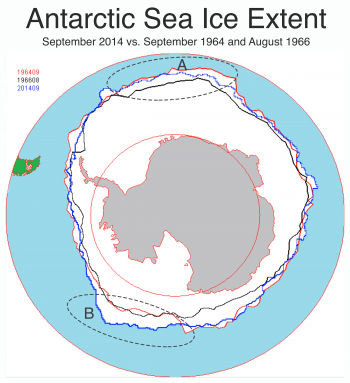

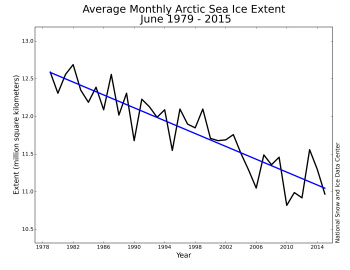

Figure 3. Monthly June ice extent for 1979 to 2015 shows a decline of 3.6% per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 average.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Arctic sea ice extent averaged for June 2015 was the third lowest in the satellite record. Through 2015, the linear rate of decline for June extent is 3.6 % per decade.

Northern Hemisphere snow cover

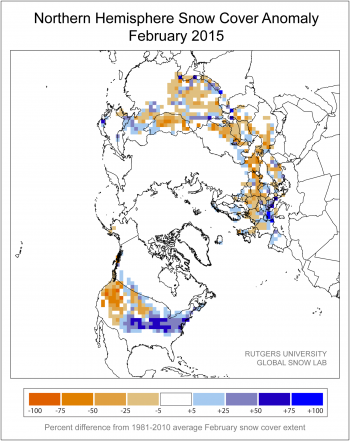

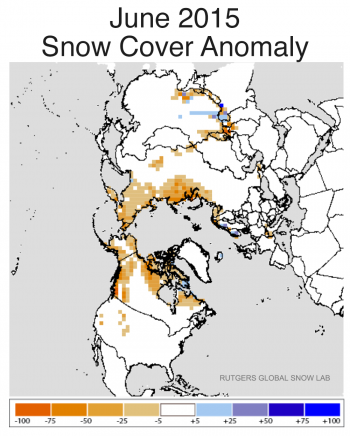

Figure 4a. This snow cover anomaly map shows how snow cover for June 2015 differs from the average snow cover for June from 1981 to 2010. Areas in orange and red indicate lower than average snow cover, while regions in blue had more snow than average.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center, courtesy Rutgers University Global Snow Lab

High-resolution image

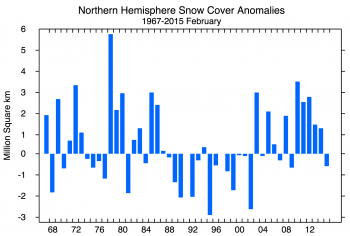

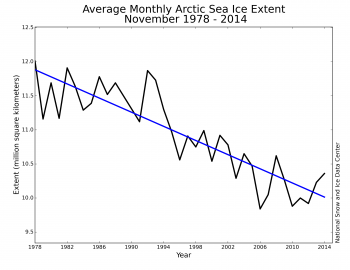

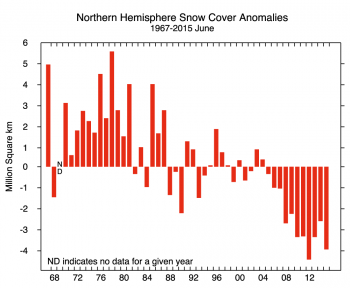

Figure 4b. The graphs shows snow cover extent anomalies in the Northern Hemisphere for June from 1967 to 2015. The anomaly is relative to the 1981 to 2010 average.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center, courtesy Rutgers University Global Snow Lab

High-resolution image

June snow cover for the Northern Hemisphere averaged 5.45 million square kilometers (2.10 million square miles), the second lowest of the 48-year record. This ranking also holds for June snow cover assessed for North America at 4.09 million square kilometers (1.58 million square miles) and Eurasia at 1.36 million square kilometers (525,000 square miles).

June snow cover was especially low over Alaska and western Canada. This is in part related to last winter’s unusual jet stream pattern, discussed in our March post. The pattern brought unusually warm conditions to the region and promoted low sea ice extent to the Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk. Recall that the restart of the Iditarod Race had to be moved from Anchorage to Fairbanks because of poor snow conditions in the Alaska Range. This spring has also been warm and dry in Alaska. These conditions have contributed to a large number of lightning-induced wildfires in the state.

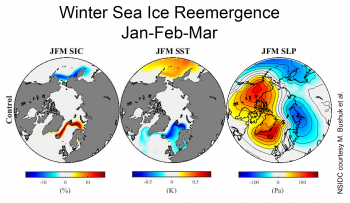

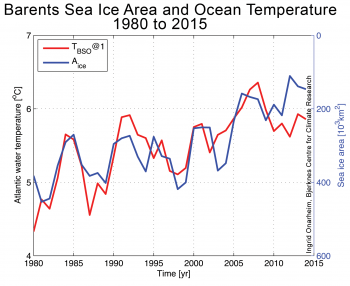

Sea ice loss and snowfall over Eurasia

Climate models predict that Arctic precipitation will increase through the 21st century. As the climate warms, the atmosphere can hold more moisture, which means a greater poleward transport and convergence of moisture by the atmosphere. The decline in Arctic sea ice extent may also play a role, as more open water will provide a moisture source. One would expect this latter effect to be most pronounced in autumn, when there will be a strong temperature (hence moisture) contrast between the open water and overlying air, promoting strong evaporation into the atmosphere. A recent study by Wegmann et al. provides evidence that more open water in the Barents and Kara seas has indeed led to an increase in autumn snowfall over Eurasia. Their analysis is based on snow observations from over 800 Russian land stations and an analysis of atmospheric moisture transport.

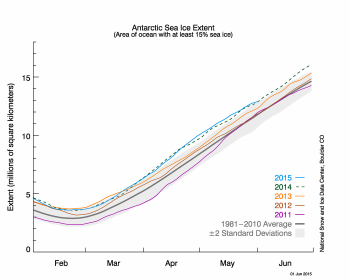

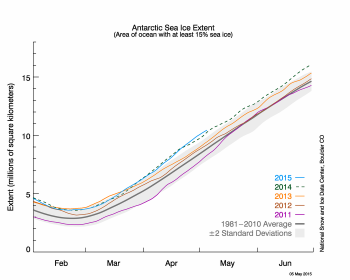

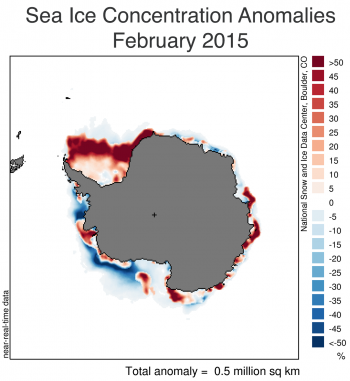

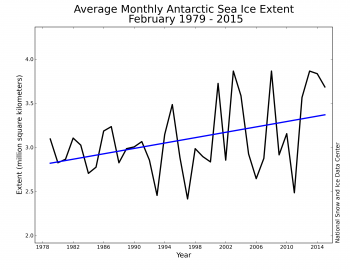

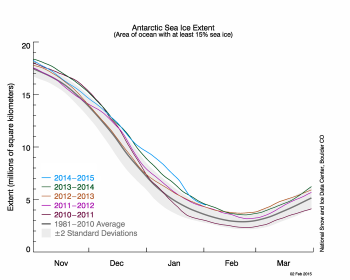

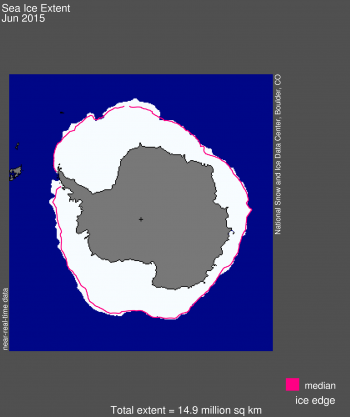

Sea ice in Antarctica

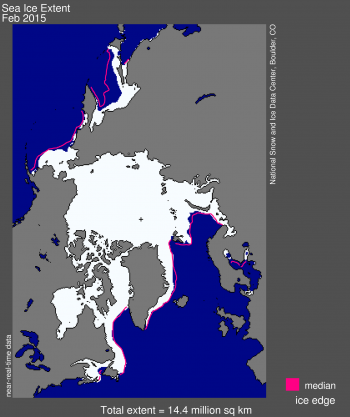

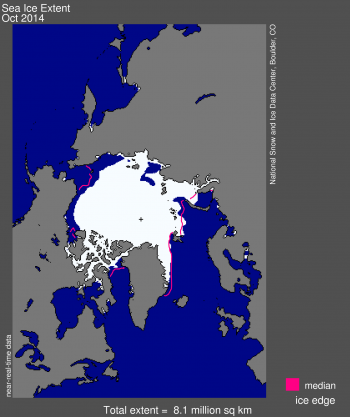

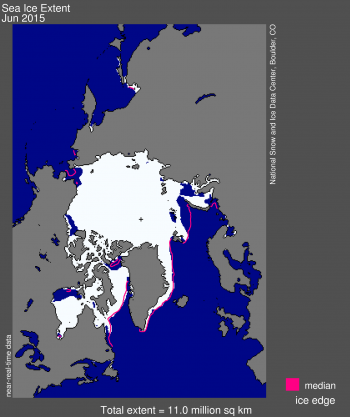

Figure 5. Antarctic sea ice extent for June 2015 was 14.9 million square kilometers (5.76 million square miles). The magenta line shows the 1981 to 2010 median extent for that month. The black cross indicates the geographic South Pole. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Sea ice extent in Antarctica averaged 14.93 million square kilometers (5.76 million square miles), the third highest June extent in the satellite record. Extent was slightly greater than the 1981 to 2010 average almost everywhere around the continent. The high amount of sea ice in the eastern Weddell and Ross seas is consistent with the pattern observed for the past several months.

Satellite data show unusually extensive sea ice growth along the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula. This new feature in sea ice growth could be influenced by the strong atmospheric wave-3 pattern that has persisted over the past few months. In a wave-3 pattern, there are three major low-pressure areas around the continent separated by three high-pressure areas. The low-pressure areas have been centered on the Antarctic Peninsula, the northwestern Ross Sea, and the eastern Weddell Sea.

Further reading

Wegmann, M., Y. Orsolini, M. Vasquez, L. Gimeno, R. Nieto, O. Bulygina, R. Jaiser, D. Handorf, A. Rinke, K. Dethloff, A. Sterin, and S. Bronnimann. 2015. Arctic moisture source for Eurasian snow cover variations in autumn. Environmental Research Letters, 10, doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/054015.