As winter turns to spring, the seasonal decline in Arctic sea ice kicks into gear. April was marked by rapid ice loss at the beginning and end of the month. Air temperatures were higher than average over much of the Arctic Ocean. In the Antarctic, sea ice extent was the highest seen in April in the satellite record. This month we introduce data sets and online tools from new sensors that—combined with older sources—provide a more complete picture of ice thickness changes across the Arctic.

Overview of conditions

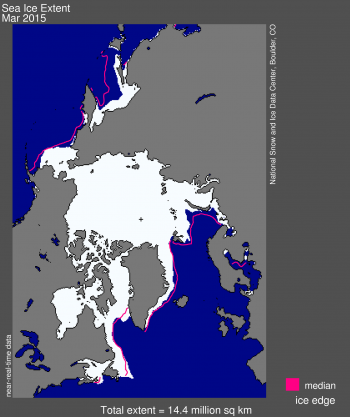

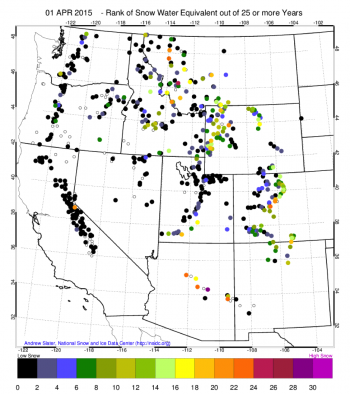

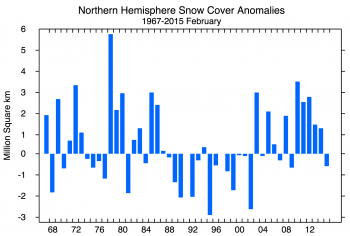

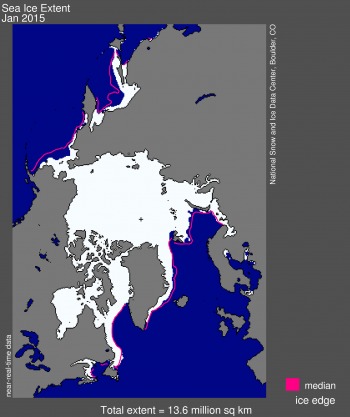

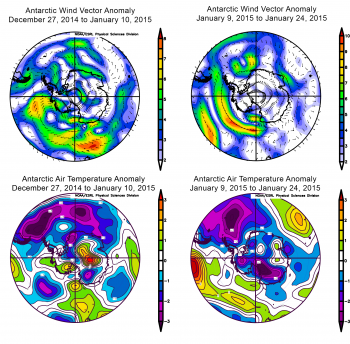

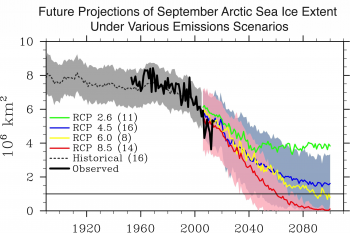

Figure 1. Arctic sea ice extent for April 2015 was 14.0 million square kilometers (5.4 million square miles). The magenta line shows the 1981 to 2010 median extent for that month. The black cross indicates the geographic North Pole. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Arctic sea ice extent for April 2015 averaged 14.0 million square kilometers (5.4 million square miles), the second lowest April ice extent in the satellite record. It is 810,000 square kilometers (313,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 long-term average of 15.0 million square kilometers (6.0 million square miles) and 80,000 square kilometers (31,000 square miles) above the previous record low for the month observed in 2007.

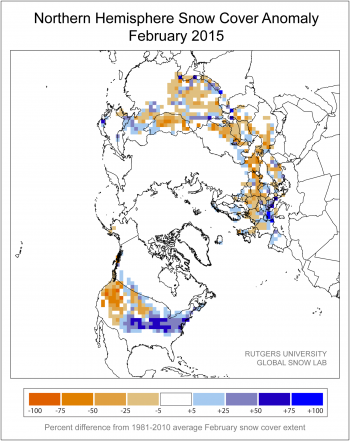

Ice extent remained below average in the Barents Sea, the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Bering Sea. Sea ice was slightly more extensive than average off Newfoundland, in the Davis Strait, and in the Labrador Sea. The Labrador Sea is an important breeding area for harp and hooded seals in early spring. More extensive ice in this region favors more seal cubs being fully weaned before the ice breaks up, increasing their chance of survival.

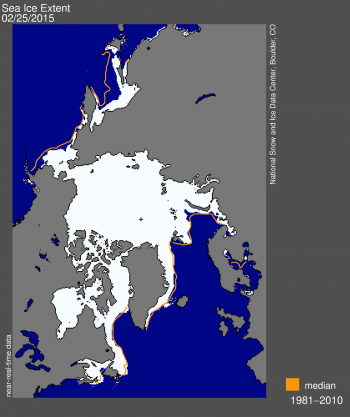

Conditions in context

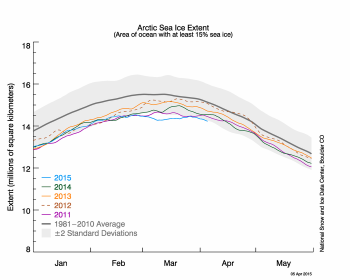

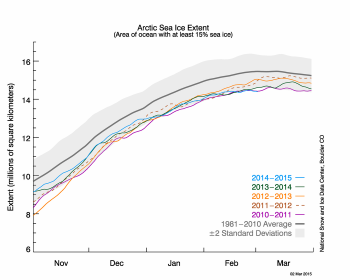

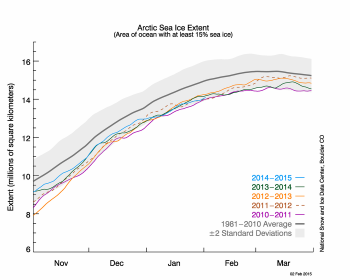

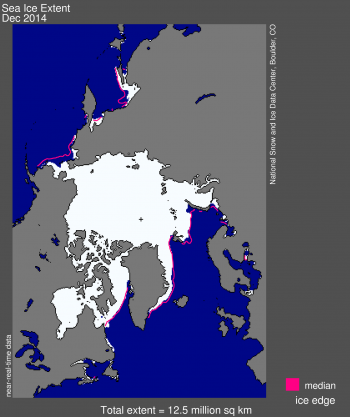

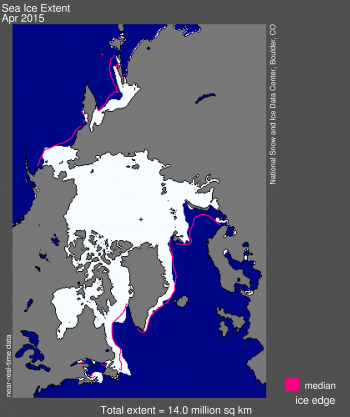

Figure 2. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of May 5, 2015, along with daily ice extent data for four previous years. 2015 is shown in blue, 2014 in green, 2013 in orange, 2012 in brown, and 2011 in purple. The 1981 to 2010 average is in dark gray. The gray area around the average line shows the two standard deviation range of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

During April, the decline in ice extent starts to accelerate, though the total ice loss over the month is generally small. April 2015 was marked by a fairly rapid decline during the first week of the month, little change during the middle of the month, and then a steep decline over the final week. Overall, extent decreased 862,000 square kilometers (333,000 square miles).

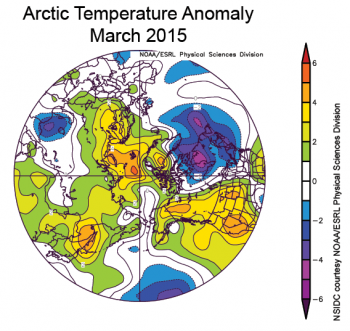

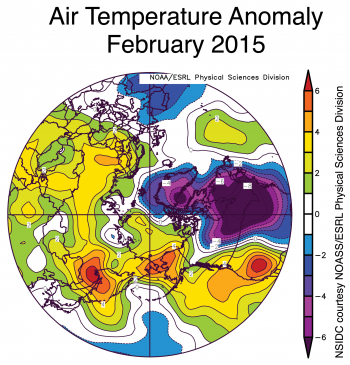

April was marked by higher than average 925 hPa air temperatures (1 to 3 degrees Celsius or 2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) throughout the Arctic, except for Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago where temperatures were 1 to 3 degrees Celsius (2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) below average. Temperatures were 6 to 8 degrees Celsius (11 to 14 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than average in the Kara Sea, linked to unusually low sea level pressure over the North Atlantic. Associated wind patterns also resulted in strong warming over the Eurasian Arctic.

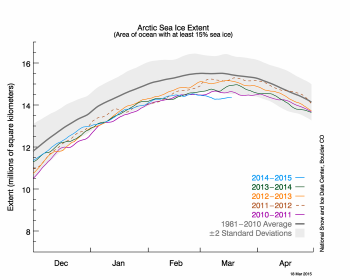

April 2015 compared to previous years

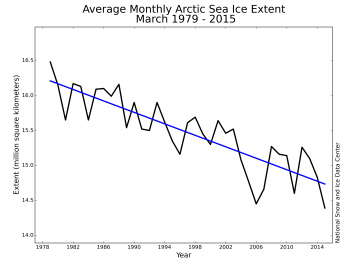

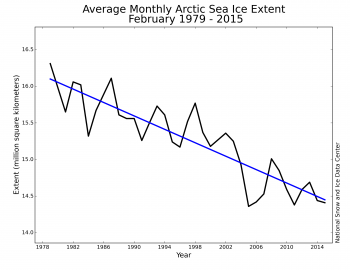

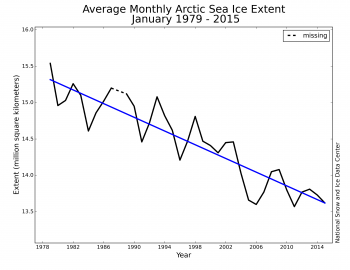

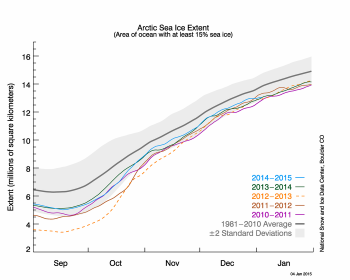

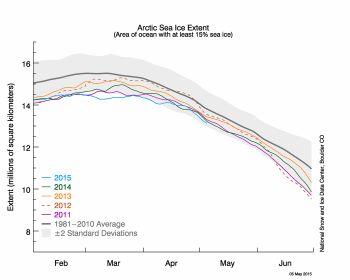

Figure 3. Monthly April ice extent for 1979 to 2015 shows a decline of 2.4% per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 average.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Arctic sea ice extent averaged for April 2015 was the second lowest in the satellite record for the month. Through 2015, the linear rate of decline for April extent is 2.4% per decade.

New data on sea ice thickness

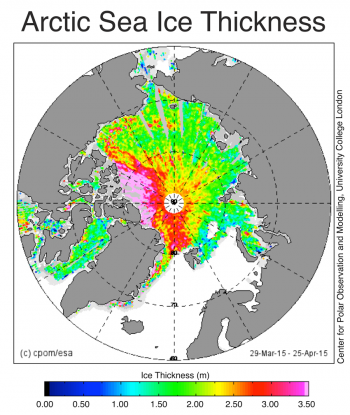

Figure 4. This map shows sea ice thickness in meters in the Arctic Ocean from March 29, 2015 to April 25, 2015.

Credit: Center for Polar Observation and Modelling, University College London

High-resolution image

Data from new sensors, combined with older sources, are providing a more complete picture of ice thickness changes across the Arctic. In a recently published paper, R. Lindsay and A. Schweiger provide a longer-term view of ice thickness, compiling a variety of subsurface, aircraft, and satellite observations. They found that ice thickness over the central Arctic Ocean has declined from an average of 3.59 meters (11.78 feet) to only 1.25 meters (4.10 feet), a reduction of 65% over the period 1975 to 2012.

In addition, near-real-time thickness data from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite are now available from the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at the University College London. The spatial pattern of ice thickness in spring is a key factor in the evolution of sea ice through the Arctic summer, and CryoSat-2 data bring the promise of regular sea ice thickness monitoring over most of the Arctic Ocean.

The data indicate that Arctic sea ice thickness in the spring of 2015 is about 25 centimeters (10 inches) thicker than in 2013. Ice more than 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) thick is found off the coast of Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago, and scattered regions of 3-meter (10 feet) thick ice extend across the Beaufort and Chukchi seas. Elsewhere, most of the ice is 1.5 to 2.0 meters (4.9 to 6.6 feet) thick, typical for first-year ice at the end of winter.

Older ice spreads out

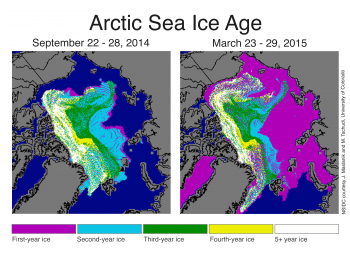

Figure 5. These ice age maps show a change in distribution of older ice from just after the summer 2014 melt season (left) and the end of March 2015 (right).

Credit: NSIDC courtesy J. Maslanik and M. Tschudi, University of Colorado Boulder

High-resolution image

Thickness estimates from CryoSat-2 data and the Lindsay and Schweiger analysis agree well with reconstructions based on sea ice age produced at the University of Colorado Boulder. Since ice gets thicker as it survives several melt seasons, ice age is a good proxy for thickness. For example, the ice thickness map from CryoSat-2 (Figure 4) and the ice age map (Figure 5) both show increased ice thickness in the southern Beaufort Sea where there was a transport of 5+ year old ice this winter. Interestingly, the ice age map identifies the tongue of ice extending towards the New Siberian Islands as second-year ice, yet the ice thickness map shows that its thickness is more similar to first-year ice.

Arctic sea ice age data are now publicly available from NSIDC and can be viewed interactively on the NSIDC Satellite Observations of Arctic Change Web site. Data are currently available through December 2012.

After the 2014 September minimum, first-year ice expanded through the winter growth season and older ice was redistributed around the Arctic Ocean. Figure 5 shows that winds have compressed second-year ice towards the coast of Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago. Old multi-year ice (4+ years old) drifted into the Beaufort and Chukchi seas and spread out, with first-year ice forming between parcels of the older ice. Some of the multi-year ice (both second-year and older) drifted out of the Arctic through Fram Strait on its way to melting in the warm waters of the North Atlantic.

Overall, the area of second-year ice decreased by more than a third during the winter, while ice of four years and more declined by about 10%. In recent years, the Beaufort and Chukchi seas have seen substantial loss of ice during summer, even of the thicker, older ice.

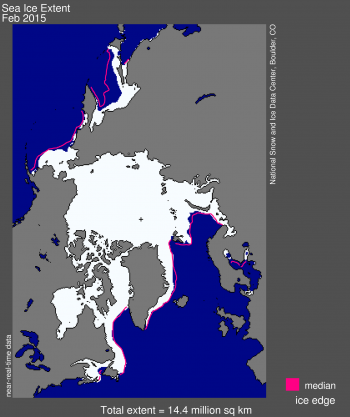

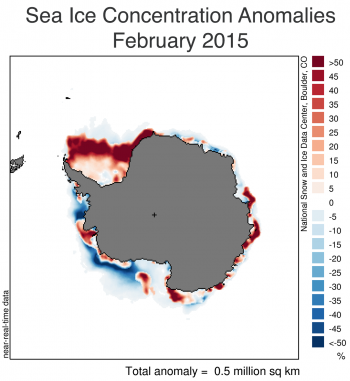

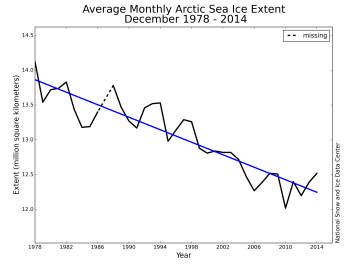

Antarctica reaches record ice extent, but temperature trends vary

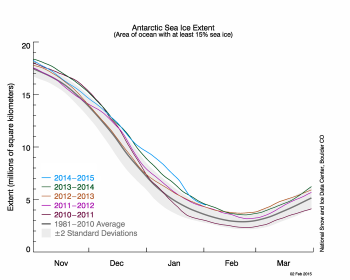

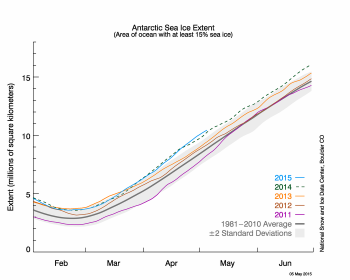

Figure 6. The graph above shows Antarctic sea ice extent as of May 5, 2015, along with daily ice extent data for four previous years. 2015 is shown in blue, 2014 in green, 2013 in orange, 2012 in brown, and 2011 in purple. The 1981 to 2010 average is in dark gray. The gray area around the average line shows the two standard deviation range of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Antarctic sea ice extent averaged 9.06 million square kilometers (3.5 million square miles) for the month and is now the highest April extent in the satellite record. April extent was 300,000 square kilometers (116,000 square miles) higher than the previous record observed in 2014, and 1.70 million square kilometers (656,000 square miles) above the 1981 to 2010 long-term average. The Antarctic April extent was also above the two standard deviations of the long-term average.

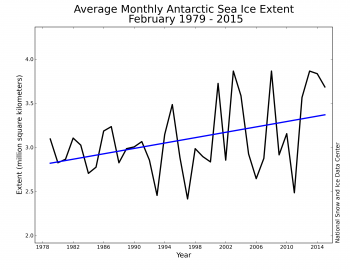

The high sea ice extent in the Antarctic was a result of above-average extent in the Weddell Sea, and slightly more expansive ice cover in the Ross Sea. Interestingly, 925 hPa air temperatures over a wide area in the Weddell Sea were 1 to 4 degrees Celsius (2 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit) above average for the month of April. Lower-than-average air temperatures (1 to 4 degrees Celsius or 2 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit below average) were found in the Ross Sea, but only in the far west and not near the regions of record ice extent. While there remains considerable year-to-year variability of sea ice extent in the Antarctic, the trend in April sea ice extent for the Antarctic from 1979 to 2015 now stands at 4.1% per decade.

References

Lindsay, R. and A. Schweiger. 2015. Arctic sea ice thickness loss determined using subsurface, aircraft, and satellite observations. The Cryosphere, 9, 269-283, doi:10.5194/tc-9-269-2015, 2015.

Tschudi, M., C. Fowler, and J. Maslanik. 2014. EASE-Grid Sea Ice Age. Boulder, Colorado USA: NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center, doi:10.5067/1UQJWCYPVX61.