By Audrey Payne

In July 1879, as the USS Jeannette left port in San Francisco en route to the North Pole, polar exploration captivated society in Europe and the United States. The United States had purchased Alaska from Russia a mere 12 years earlier, the first International Polar Year was just two years away, and no man had yet to reach the Pole. What lay at the top of the world was still shrouded in mystery. Was it a warm inland sea, a sheet of ice, or open ocean? This was the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration, and glory, scientific discovery, and financial gain awaited the explorer who could get there first and find the answer. This is what the USS Jeannette’s captain, George W. De Long, was after.

Many lives were lost in the pursuit of discovery during this time, however, including the majority of the crew of the USS Jeannette. But the memory of that crew lives on through the invaluable scientific information that they laboriously collected and, almost miraculously, returned to civilization, even as many of them succumbed to the elements during their journey. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NOAA@NSIDC) program still stores some of these data today that are related to sea ice thickness, making them available to the public more than a century after that ill-fated voyage.

These data provide an important historical record of a region that is swiftly transforming because of climate change, and allow scientists to compare more recent satellite-data-derived data with historical data to create a much longer record of Arctic sea ice thickness.

A motley crew

De Long, a US naval officer, headed the Jeannette expedition on the dime of newspaper tycoon James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the New York Herald, who thought the story of reaching the North Pole would sell a lot of newspapers. De Long had visited the Arctic during a previous expedition to Greenland and ached to become the first man to reach the North Pole. He spent five years meticulously planning the expedition—outlining a route through the Bering Strait that had not been sailed before, reinforcing the ship to prevent it from collapsing under the pressure of the thick slabs of ice, and collecting instruments to take scientific observations during the journey. The ship was outfitted with several pieces of scientific equipment for taking observations along the way, including a darkroom, observatory, current trackers, wind trackers, and magnetic and meteorological instruments.

De Long’s crew, numbering 33 including himself, was a diverse group. His officers were US Naval Academy graduates, and they were accompanied by sailors, whalers, and cooks that had immigrated from Denmark, Norway, Scotland, England, and China, as well as a civilian naturalist and meteorologist. The ship set off from San Francisco on July 8, 1879, and upon arriving at St. Michael, a port in Alaska, in August, two experienced Inuit dog drivers and several sled dogs joined the expedition. During the voyage, the scientists on board took various observations and measurements. They documented their experiences, took water samples, preserved local species, and measured the ocean depth, currents, salinity, air and water temperature, ice thickness, snow thickness on the ice, and ice characteristics.

Winter conditions and plan B

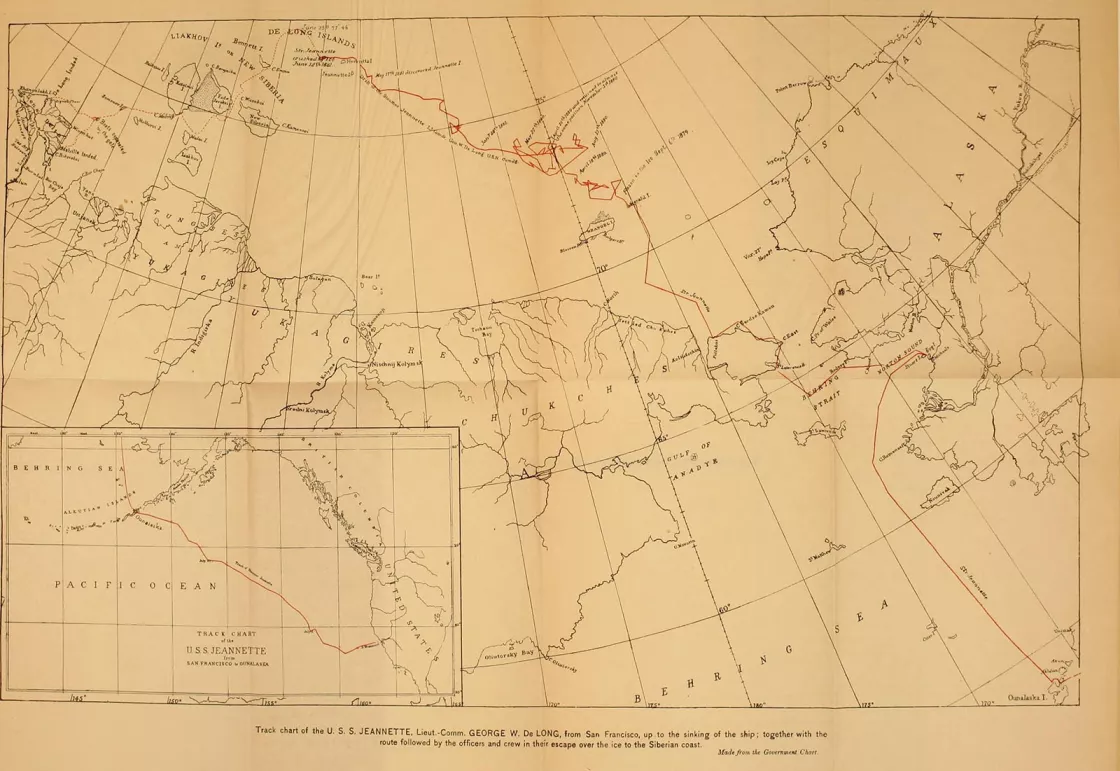

From St. Michael, the USS Jeannette passed through the Bering Strait without incident, aiming for Wrangel Island, then called Wrangel’s Land, located in the Arctic Ocean between the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas. De Long believed that Wrangel’s Land, which had previously been discovered by whalers, was not an island but actually part of a massive transpolar continent that connected to Greenland. Here, De Long hoped to set up winter quarters. However, the crew never made it to the island.

Arctic sea ice waxes and wanes with the seasons. It builds throughout the autumn and winter, reaching a seasonal maximum around March, then diminishes in the spring and summer, reaching a seasonal minimum around September. And in early September 1879, as air temperatures dropped, the crew quickly found themselves battling ice conditions. De Long pivoted, aiming instead for Herald Island, which was about 28 kilometers (17 miles) from the ship, but that too was futile. Before long, the ship was completely trapped in ice, forced to drift with tide and wind.

The crew was able to hunt on the ice, surviving through the dark Arctic winter on foods like seals, walruses, sea gulls, and polar bears. They even overcame a near-sinking that January because some of the crew acted quickly by jumping into the freezing cold water to repair the ship. As summer approached, they remained optimistic that the ship would be released from the ice as air temperatures increased. However, the USS Jeannette remained trapped in sea ice for nearly two years. The crew continued taking scientific measurements and observations during this time.

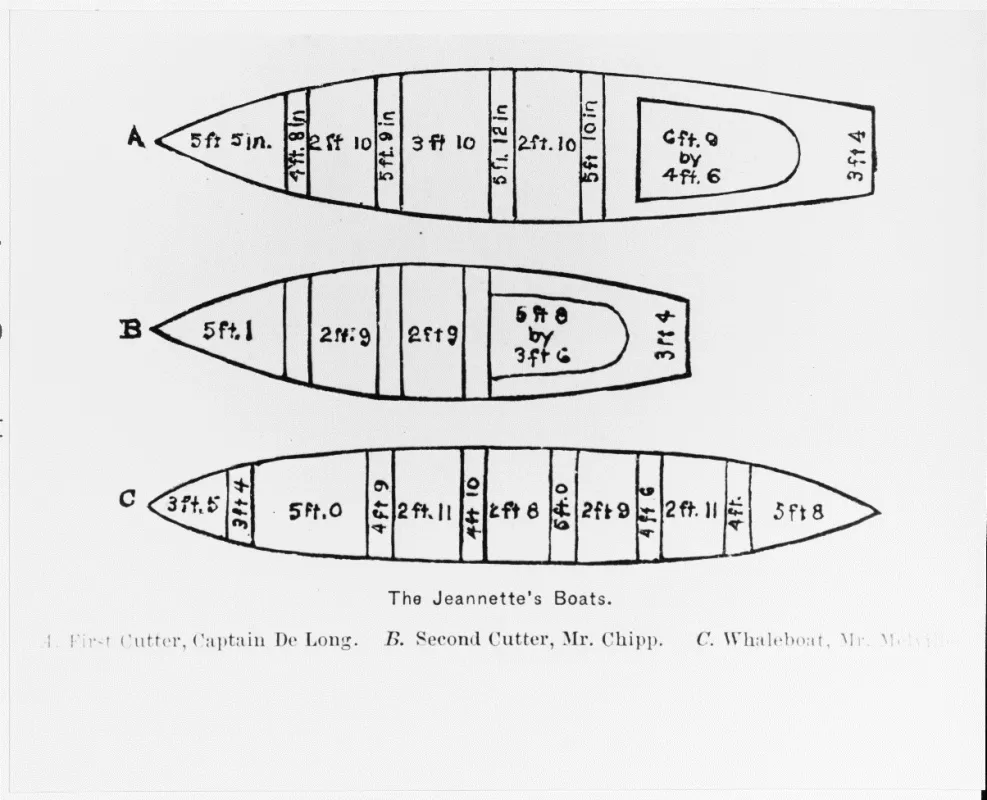

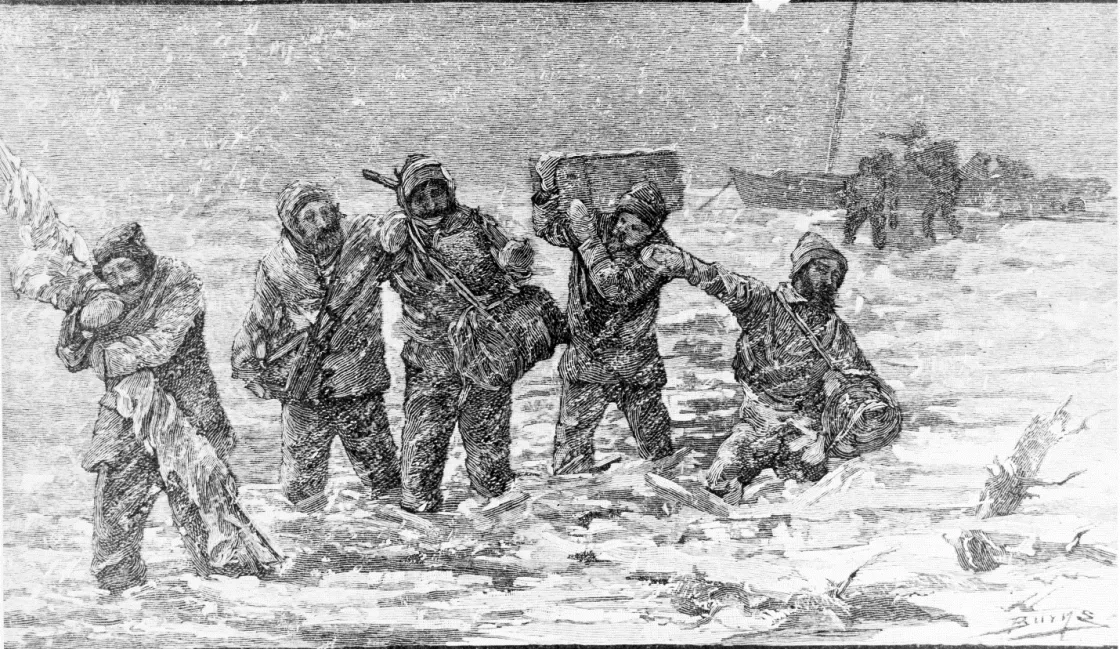

After only one short day of release in mid-June 1881, the ice returned with a vengeance, crushing the ship and damaging it beyond repair, forcing the crew to evacuate. The ship sank on June 12, 1881, around 560 kilometers (350 miles) north of the Siberian coast, but before it did, the crew was able to rescue their smaller boats, sleds, provisions, and logbooks from it. De Long insisted that the ship’s logbooks, which included their scientific observations, were not to be left behind. The crew then traveled over the ice, dragging their boats packed with supplies behind them, for months. They reached a small uncharted island in July but abandoned it in August in favor of trying to reach the mainland before another long Arctic winter set in. En route, they sailed past several small islands by boat, of which they had three: a large cutter, a small cutter, and a whaleboat, resting again briefly on Semyonovsky Island, located about 185 kilometers (115 miles) from Siberia, before setting sail one final time toward the mainland.

Separated

Immediately upon leaving Semyonovsky Island, weather conditions worsened, and the three boats were separated. Thirteen men including De Long went on the large cutter, eight men went on the small cutter, and 11 men went on the whaleboat. The small cutter is presumed to have never made it to shore. No trace of the ship or the eight men were ever found. The whaleboat was able to reach a fishing camp and received help from native Yakut and Evenki people, who played a critical role in saving their lives by treating their frostbite, sharing what little food they had, and sheltering them from the brutal Siberian weather. Each of those men survived, and they sent word home of what befell them. The men from the large cutter were able to wade to shore but found themselves in dire straits as they searched in vain for civilization. The two fittest men from that party, William Nindemann and Louis Noros, were sent out to hunt and seek help as their comrades perished one by one. Nindemann and Noros were able to reconnect with the whaleboat party with the help of the Yakut and Evenki people, and they were the sole survivors from their group as a result. De Long’s party continued on slowly, but never found civilization, eventually succumbing to starvation and the elements. De Long was likely one of the last to perish, leaving his last journal entry on October 30, 1881.

With the help of the Russians, most of the survivors from the whaleboat began their long journey home in January 1882. However, Nindemann, Noros, and George Melville, a naval officer, engineer, and the leader of the whaleboat party, remained behind in Siberia in order to search for De Long and the rest of the crew, again with the help of the Yakut people. The spring floods would come soon, so they knew they were racing against time to find clues of where the crew ended up. In March, five months after Nindemann and Noros originally left the large cutter party to seek help, they discovered the remains of De Long’s party, frozen in the ice along with De Long’s journal, which detailed their final days, and the ship’s logbooks. De Long and his party had carried the logbooks to their final resting place, never abandoning them even as they crept closer and closer to death. Nindemann, Noros, and Melville carried the logs the remaining 19,300 kilometers (12,000 miles) home to Washington, DC.

Contributions to science

While the USS Jeannette expedition was ultimately considered a failure, it did contribute much to science. The crew explored and mapped hundreds of miles of uncharted territory, provided oceanographic and metrological measurements, and collected natural history specimens. They also disproved the theory that a temperate current called the Kuro Siwo flowed from the Bering Strait to the North Pole. De Long was the first to test out this route, and the expedition failed in part because this theory about the current was incorrect. The crew also discovered two unknown islands—Henrietta Island and Jeanette Island—which De Long named after his mother and the ship, respectively.

While these accomplishments were certainly notable at the time, what may be even more impressive is that the Jeannette data are still being used today. “The greatest contribution of these data is not that they resulted in new or eye-opening discoveries,” said Florence Fetterer, lead of the NOAA@NSIDC program, of the sea ice thickness measurements taken during the expedition. “It is that they contribute to the extremely limited number of sea ice thickness measurements that we have from the 1800s, with very few from that part of the Arctic.”

Sea ice cover has changed drastically even just during the satellite era, and these records are invaluable for scientists who are working to understand the state of Arctic ice cover then and now. Researchers can pair these 34 observations from the Jeannette expedition, for example, with other old data like the ice charts compiled by the Danish Meteorological Institute. Together, these observations can contribute to the long time series needed for climate or regional process studies and help us to better understand the changes that have taken place in this region. And this is just one example of a use-case for the Jeannette data. In addition to these data available at NSIDC, weather observations from the USS Jeannette and many other ships can be found using the Zooniverse Old Weather portal, and the US Navy has even more data beyond that.

The USS Jeannette crew has long since passed, but their story and their data live on, and continue to contribute to the scientific record.

Get data

Sea ice thickness data from the USS Jeannette expedition, along with 49 other expeditions, are available through NOAA@NSIDC within the data set entitled “On-Ice Arctic Sea Ice Thickness Measurements by Auger, Core, and Electromagnetic Induction, from the Late 1800s Onward, Version 2.” These records consist of sea ice thickness along with date, time, and location of the measurements from 1879 to 2016. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) scientist Benjamin Holt built the collection of ice thickness measurements and is expected to add to it further in the future.

Related data at NOAA@NSIDC

- SCICEX: Submarine Arctic Science Program, https://nsidc.org/scicex

- Sea-ice Thickness and Draft Statistics from Submarine ULS, Moored ULS, and a Coupled Model, Version 1, https://nsidc.org/data/g02194/versions/1

- Submarine Upward Looking Sonar Ice Draft Profile Data and Statistics, Version 1, https://nsidc.org/data/g01360/versions/1

- On-Ice Arctic Sea Ice Thickness Measurements by Auger, Core, and Electromagnetic Induction, from the Late 1800s Onward, Version 2, https://nsidc.org/data/g10011/versions/2

- Morphometric Characteristics of Ice and Snow in the Arctic Basin: Aircraft Landing Observations from the Former Soviet Union, 1928-1989, Version 1, https://nsidc.org/data/g02140/versions/1

- AWI Moored ULS Data, Greenland Sea and Fram Strait, 1991-2002, Version 1, https://nsidc.org/data/g02139/versions/1

- Unified Sea Ice Thickness Climate Data Record, 1947 Onward, Version 1, https://nsidc.org/data/g10006/versions/1

References

Benjamin, Daniel. “Arctic Expeditions of the 19th Century.” June 1, 2001. PERC. https://perc.org/2001/06/01/arctic-expeditions-of-the-19th-century/

Danish Meteorological Institute and National Snow and Ice Data Center. Compiled by V. Underhill and F. Fetterer. “Arctic Sea Ice Charts from Danish Meteorological Institute, 1893 - 1956, Version 1.” 2012. Boulder, Colorado. NSIDC: National Snow and Ice Data Center. doi:10.7265/N56D5QXC

Henderson, Bruce. “Who Discovered the North Pole?” Smithsonian Magazine. April 2009. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-discovered-the-north-pole-116633746/#:~:text=And%20here%20was%20the%20American,alone%20would%20have%20been%20astounding.

“In The Kingdom Of Ice: The Voyage Of The USS Jeannette.” November 8, 2015. Viewpoints Radio. https://viewpointsradio.org/in-the-kingdom-of-ice-the-voyage-of-the-uss-jeannette/

Holt, B. 2019. “On-Ice Arctic Sea Ice Thickness Measurements by Auger, Core, and Electromagnetic Induction, from the Late 1800s Onward, Version 2.” Boulder, Colorado USA. NSIDC: National Snow and Ice Data Center. doi:10.7265/wz0k-4p60

Kratz, Jesse. “Mystery of the Arctic Ice: Who was First to the North Pole.” Pieces of History. April 6, 2022. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2022/04/06/mystery-of-the-arctic-ice-who-was-first-to-the-north-pole/

Kwok, R. and D. A. Rothrock. “Decline in Arctic sea ice thickness from submarine and ICESat records: 1958-2008.” August 6, 2009. Geophysical Research Letters 36, 1–5. doi:10.1029/2009GL039035

“Log Books of the United States Navy, 19th and 20th Centuries.” Naval History Homepage. January 30, 2018. https://www.naval-history.net/OW-US/Jeannette/USS_Jeannette.htm

Ranis, Flora. “From Hopeless to Heroic: The Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette.” August 2016. International Journal of Naval History. https://www.ijnhonline.org/from-hopeless-to-heroic-the-polar-voyage-of-the-uss-jeannette/