By: Audrey Payne

What defines a glacier? What are the world’s three largest glaciers? What are the largest glaciers in each region of the world? As often as the rapidly changing cryosphere is making headlines, from stories on dwindling Arctic sea ice to thawing permafrost to melting ice sheets, one would think the answers to these questions would be obvious and easy to find. But when NSIDC’s Ann Windnagel began investigating, she found they were not as straightforward as she was expecting.

“It’s so surprising that we don’t already know this,” she said, “but there are different definitions, depending on where you get your information, for a glacier, ice sheet, or ice cap. Finding out what constitutes a glacier was the most challenging part of this entire project.”

Strengthening a partnership

Windnagel, a project manager for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) at NSIDC program, was working toward a professional certificate in Earth Science Data Analysis through the University of Colorado Boulder when she was invited to take part in a work exchange with the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) in Zurich, Switzerland. WGMS has been a longtime NOAA at NSIDC partner, and, after years of mentoring WGMS interns and postdoctoral researchers at NSIDC, she jumped at the chance to see how her Swiss cohorts lived and worked at home.

While there, Windnagel was tasked with developing a project that would benefit both NSIDC and WGMS. She decided to perform a systemic analysis of the largest glaciers in the world, something never done before.

“Glaciers are melting at alarming rates due to climate change,” Windnagel said. “And glacial melt can and will have all sorts of detrimental effects on society, such as rising sea levels and dwindling fresh water supplies. Studying glaciers offers insight into how climate change is affecting different areas of the world differently and important knowledge to help us plan for the future.”

In addition to supporting NSIDC and WGMS knowledge, this project also aligned with the mission of NOAA, which is “to understand and predict changes in climate, weather, oceans, and coasts, to share that knowledge and information with others, and to conserve and manage coastal and marine ecosystems and resources.”

Gathering data

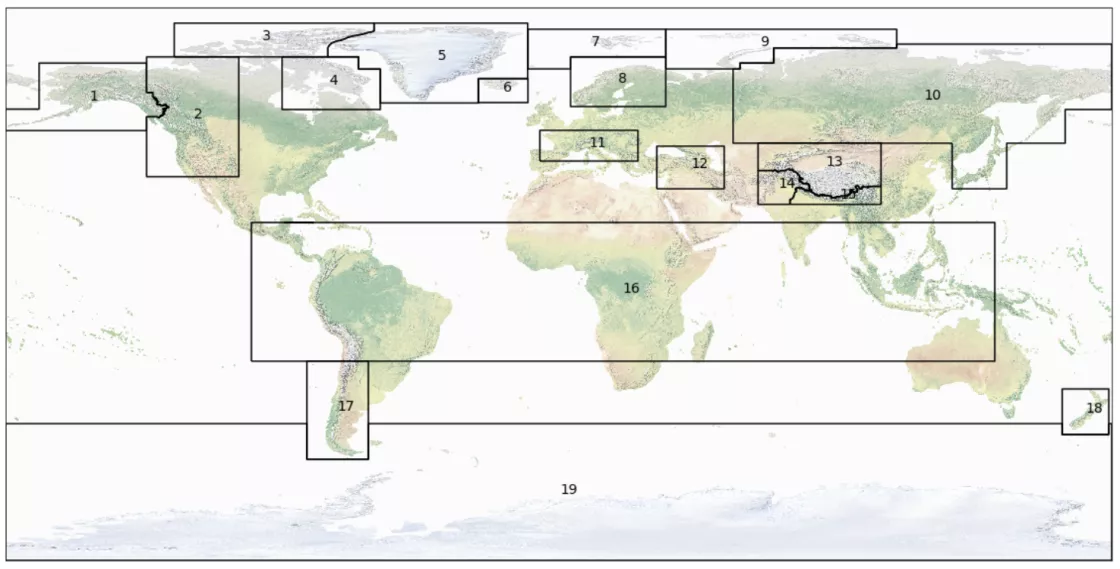

As part of her global analysis of glaciers, Windnagel set out to identify the largest glaciers worldwide and within each of the 19 glacier regions recognized by the Global Terrestrial Network for Glaciers. Windnagel believes that identifying these glaciers is important for a few reasons. It helps to organize data, gives people perspective on how much water is stored in glaciers, and could help scientists and policymakers understand which glaciers are likely to have the biggest impacts, allowing them to better focus resources to monitor glacial melt in the most at-risk areas.

To conduct her analysis, Windnagel gathered data from two well-known global glacier data sets: the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) project and the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI). Using shapefiles from both data sets, she determined the 10 largest glaciers by area from each, then compared the two, investigating mismatches using scientific literature.

As she dove into the data, more questions began to arise. For example, what is a glacier versus an ice sheet or ice cap? When glaciers break apart, are the pieces still part of the same glacier or do they create new ones? Why do organizations disagree on the definition of a glacier?

“I’m not a glaciologist by trade,” said Windnagel. “I had no idea even that the definition of a glacier was up in the air. So, working on this project and working this closely with glaciologists everyday was eye-opening. I learned so much.”

Ultimately, Windnagel chose to follow the GLIMS definition of a glacier for the project, which states that a glacier is “a mass of ice on the land surface which flows downhill under gravity and is constrained by internal stress and friction at the base and sides. In general, a glacier is formed and maintained by accumulation of snow at high altitudes, balanced by melting at low altitudes or calving into the sea or lakes.”

The takeaway

Windnagel spent five weeks working on her project at the WGMS office in Zurich. According to the GLIMS data set, the three largest glaciers in the world are Vatnajokull Glacier in Iceland, Flade Isblink Ice Cap in Greenland, and Seller Glacier in Antarctica. On the other hand, according to the RGI data set, the three largest glaciers in the world are Flade Isblink Ice Cap in Greenland, Carney Island Ice Cap in Antarctica, and Seward Glacier in Alaska. Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier, which is widely thought to be the largest glacier in the world, did not make the top three from either data set. This is because, according to the GLIMS definition of a glacier, Pine Island Glacier is not a true glacier at all—it is an ice stream flowing into the Amundsen Sea faster than the rest of the surrounding mass from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

While Windnagel was able to identify the largest glaciers in the world, she still needs to validate her findings. In addition, she has many questions left to answer now that she has returned stateside and continues to work on the project. For example, finding the largest glaciers in each region has proven more difficult because glacier data sets, including GLIMS, are not always current in each region. In order to finish her project, Windnagel will need the help and perspective of regional glacial correspondents to validate her data. Windnagel will also continue to investigate the differences between ice caps and glaciers and perform a glacial retreat analysis to determine which of the world’s glaciers are melting the fastest. In the future, she would like to use her findings to create new glacier data sets and educational and outreach materials.

Further Reading:

Bishop, M. P., Olsenholler, J. A., Shroder, J. F., Barry, R. G., Raup, B. H., Bush, A. B., ... & Kääb, A. 2004. Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS): remote sensing and GIS investigations of the Earth's cryosphere. Geocarto International, 19(2), 57-84. doi.org/10.1080/10106040408542307