During April, Arctic sea ice extent declined at a steady pace, remaining just below the 1979 to 2000 average. Ice extent for April 2010 was the largest for that month in the past decade. At the same time, changing wind patterns have caused older, thicker ice to move south along Greenland’s east coast, where it will likely melt during the summer. Temperatures in the Arctic remained above average.

Overview of conditions

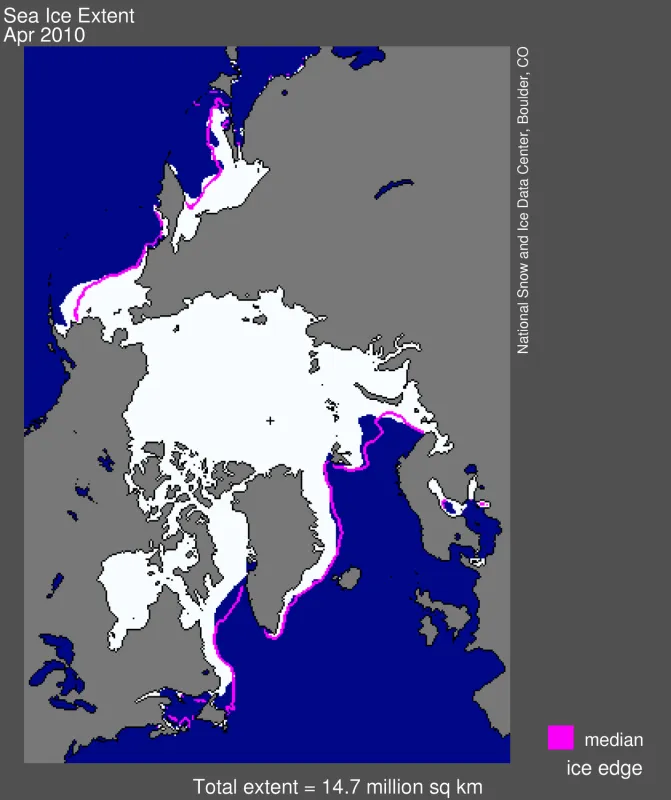

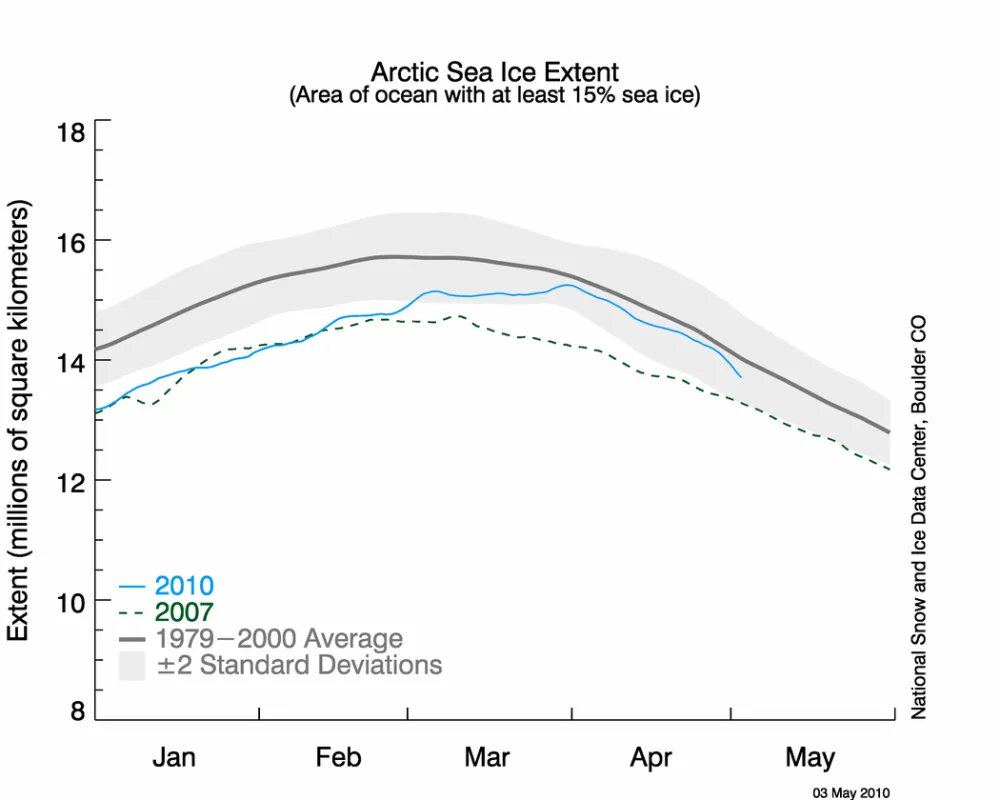

Arctic sea ice extent averaged 14.69 million square kilometers (5.67 square miles) for the month of April, just 310,000 square kilometers (120,000 square miles) below the 1979 to 2000 average. The rate of ice extent decline for the month was also close to average, at 41,000 kilometers (16,000 square miles) per day. As a result, April 2010 fell well within one standard deviation of the mean for the month, and posted the highest April extent since 2001.

Ice extent remained slightly above average in the Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk, and slightly below average in the Barents Sea north of Scandinavia, and in Baffin Bay, where ice extent remained below average all winter.

Conditions in context

The very late maximum ice extent, on March 31, means that the melt season started almost a month later later than normal.

As we noted in last month’s post, the late growth in ice extent came largely from expansion in the southernmost Bering Sea, Barents Sea, and Sea of Okhotsk. These areas remained cool, with northeasterly and northwesterly winds, keeping the overall ice extent close to the average for the month of April.

April 2010 compared to past years

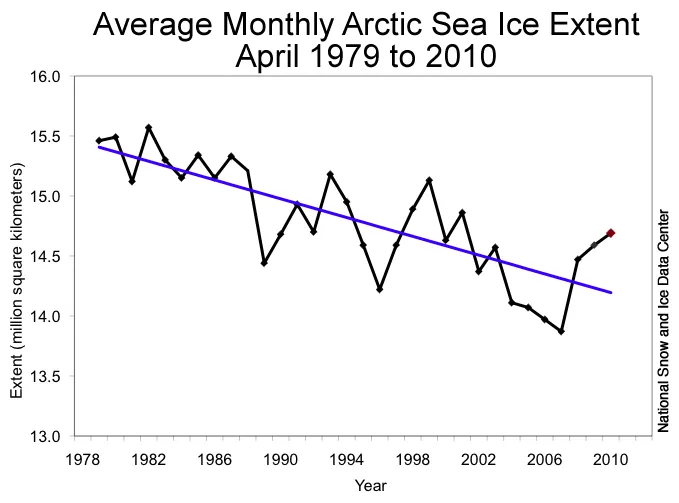

Average ice extent for April 2010 was 820,000 square kilometers (317,000 square miles) greater than the record low for April, observed in 2007, and 310,000 square kilometers (120,000 square miles) below the average extent for the month. The linear rate of decline for April over the 1979 to 2010 period is now 2.6% per decade.

Continued high temperatures in the Arctic

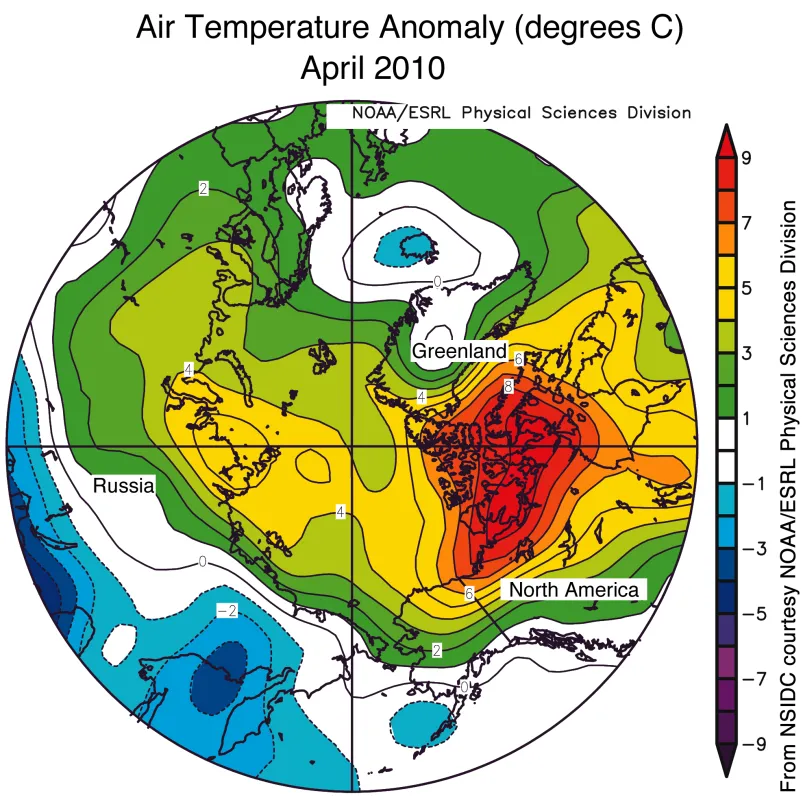

Despite the late ice growth, Arctic air temperatures remained persistently warmer than average throughout the winter and early spring season. April temperatures were about 3 to 4 degrees Celsius (5 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit) above average across much of the Arctic Ocean, and up to 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal in northern Canada. Conditions in the Arctic were part of a trend of warmer temperatures worldwide in the past few months. An exception was the Sea of Okhotsk, where cool April conditions and northerly winds have slowed the rate of ice retreat. Visit the NASA GISS temperatures Web site for more information on global and Arctic temperatures over the past few months.

A closer look

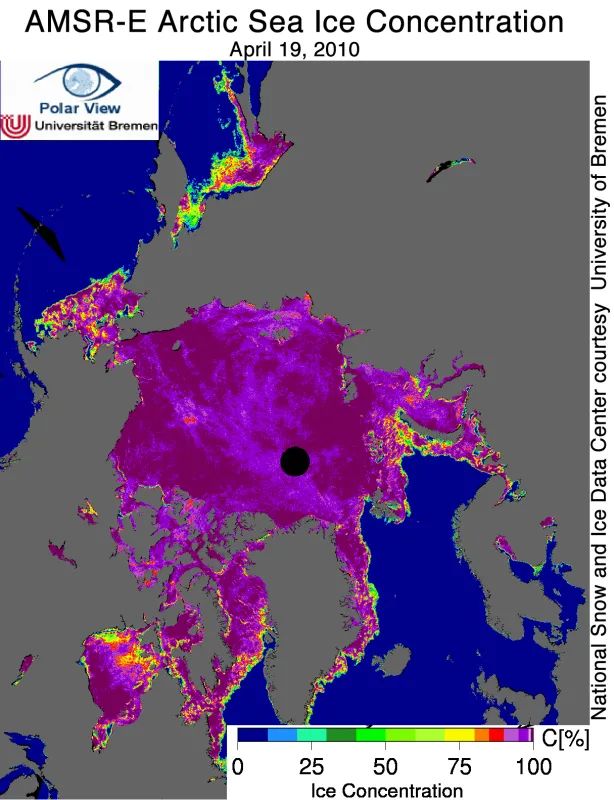

While NSIDC primarily uses the Special Sensor Microwave/Imager (SSM/I) and Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder (SSMIS) sensors to track long-term conditions, we also look at data from higher-resolution sensors to assess current conditions in more detail. An image from NASA’s Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer – Earth Observing System (AMSR-E) sensor from April 19 reveals numerous polynyas, or areas of open water in the pack ice in the Bering Sea, and broad areas of more scattered ice cover in the Sea of Okhotsk, Barents Sea, and Hudson Bay. Such conditions usually indicate that ice is about to retreat rapidly. Over much of the coastline in this image, there is an indication of low-concentration sea ice. This is an artifact of mixed pixel areas, which contain both water and land. The same effect is seen occasionally in the SSM/I record.

Ice motion in the Arctic Ocean

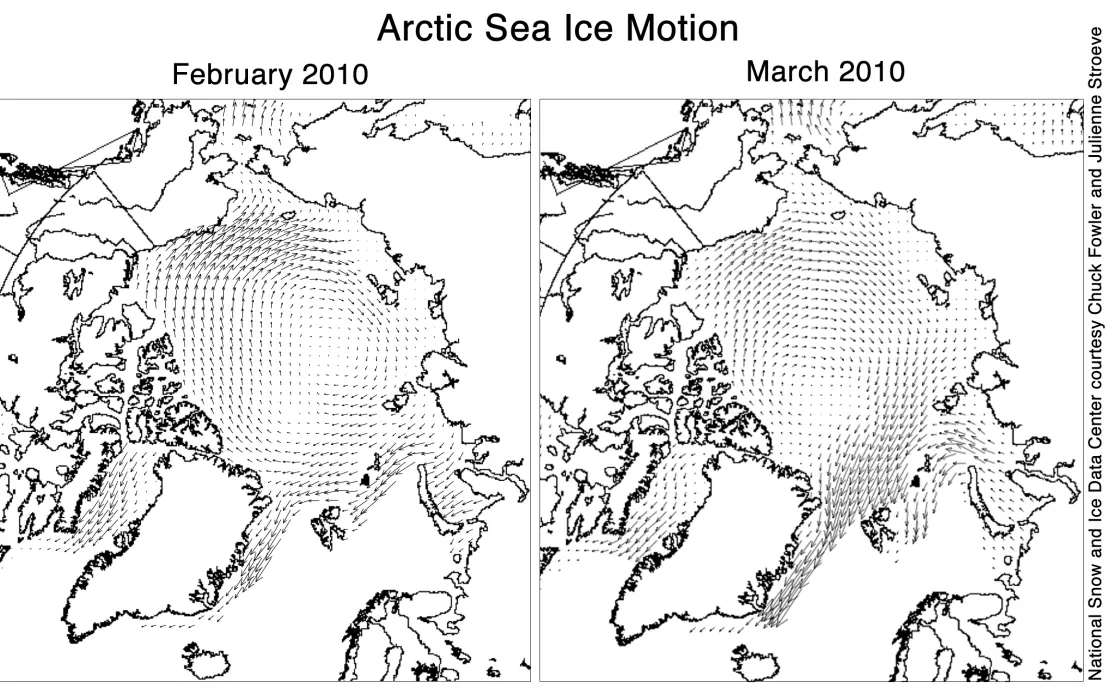

The thickness of sea ice at the beginning of spring plays a role in how much ice survives summer melt, so we pay attention to factors that influence ice thickness, such as ice motion. Ice motion is determined by winds and other factors, which in turn are influenced by weather patterns such as the Arctic Oscillation.

In February, the strongly negative phase of the Arctic Oscillation was associated with a strong Beaufort Gyre, enhancing ice motion from the western to the eastern Arctic. A weaker Transpolar Drift Stream also slowed the movement of ice from the Siberian coast of Russia across the Arctic basin, and reduced ice flow out of Fram Strait. The wind pattern changed in March, when the Arctic Oscillation went into a more neutral phase. As a result, the flow of ice sped up through Fram Strait and along the coast of Greenland. This pattern helps to remove older ice from the central Arctic, pushing it toward the warm waters of the North Atlantic, where it will melt.

In past decades, a strong Beaufort Gyre tended to retain old, thick ice in the Arctic Ocean. However, this may no longer hold true, because in recent years ice transiting the Beaufort Gyre tends not to survive the summer melt season. This summer’s weather conditions may be key to the survival of this older ice.

Further Reading

The SEARCH Sea Ice Outlook, an international, community-wide discussion of the upcoming September Arctic sea ice minimum, is once again underway. This year, a companion effort, the Sea Ice for Walrus Outlook (SIWO), will provide assessments and short-term (7- to 10- day) predictions of ice conditions in the Alaska region. SIWO is a resource for Alaska subsistence hunters, coastal communities, and other interested parties. See their Web page for regular updates and high-resolution satellite imagery of the region.

The University of Washington Polar Science Center has begun providing Arctic sea ice volume anomalies. Routine, long-term observation records of ice volume are limited, so the anomalies are calculated by assimilating observations of sea ice concentrations into model simulations. The anomalies are updated every few days.