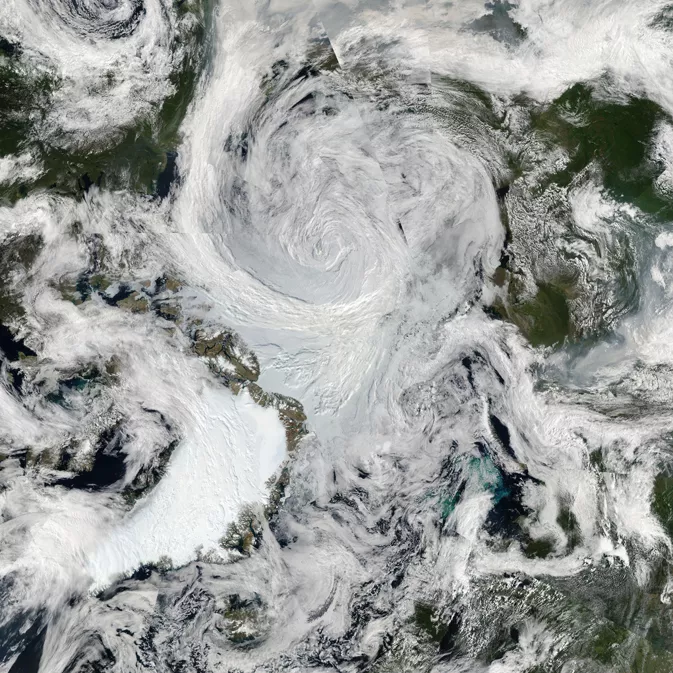

The Big One

The Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 lifted out of Siberia on August 2, swirling in a counter-clockwise rotation up into the Arctic. As one of the most extreme Arctic cyclones ever recorded, its consumption of an already low sea ice extent raised many concerns. Now Arctic cyclones are garnering attention, but is all the hype warranted? “People seem to have this thought that all this storminess is unusual,” said Mark Serreze, an Arctic climatologist and center director at NSIDC. “Well it’s not. It simply isn’t. Summer is the time for cyclones.”

Arctic summers are not calm. In fact, the months of August and September see a maximum amount of cyclonic activity. Not every summer is very stormy, but overall, the Arctic is the Arctic for a reason. How much did the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 contribute to ice loss? Less than 5 percent, according to a study led by Jinlun Zhang and published in Geophysical Research Letters. The scientists point out that 2012's record loss was 18 percent greater than the previous low, set in 2007, meaning the record low was going to get there with or without the big one.

The rise of cyclones

Adding to confusion of the Arctic’s storminess, the Atlantic side can be calm in the summer. But this isn’t the area being discussed in terms of cyclone activity. In the Northern Beaufort Sea, north of Alaska, summer is tempestuous. “The reason we have storms in the first place is that they do a job—transferring heat and momentum poleward,” Serreze said. In the Northern Hemisphere, winters are stormier because of the temperature gradient between the Arctic, which is dark and cold, and the equatorial regions, which are sunny and warm. “But embedded within that overall pattern, what happens on a regional basis can be quite different,” Serreze said.

During an Arctic summer, temperature gradients develop between the Arctic Ocean and the snow-free land, forming the Arctic frontal zone, where the land heats up strongly in contrast to the ocean along the coast. Most cyclones generate along this frontal zone and then migrate into the central Arctic Ocean. Are the storms getting stronger? “No,” Serreze said. “Most of the evidence is actually showing that the frequency of stormy months is decreasing, favoring fair weather conditions. It’s not clear why, but it’s what’s been observed lately.”

What do cyclones do to sea ice?

Cyclones do three things to sea ice. They spread out ice to cover a larger area, forming space between ice floes, and increasing ice extent. They bring on cool conditions. And they cause precipitation, which even in the peak of summer is still between 40 to 50 percent in the form of snow. Storms are good for the Arctic. Snow reinforces ice by increasing the amount of sunlight reflected back into the atmosphere, helping to cool the region. When rain falls, it is near freezing; so it doesn’t melt snow like a warm rainstorm over snow banks in lower latitudes. “Statistically speaking,” Serreze said, “summers with lots of cyclones have less ice loss than summers with fewer storms. That’s pretty clear.” That’s what happened this past June. A stormy pattern slowed the rate of ice loss. “Having said that,” Serreze said, “the impacts of an individual storm may not follow that rule, and maybe importantly, the rules are starting to change.”

When a storm breaks up the ice causing ice sprawl, it accelerates ice loss because the darker spaces of open ocean water, absorb more solar energy and increase melting. “If you looked at it that way,” Serreze said, “okay, I’d buy it. But that’s not the only thing that’s happening.” Stormy patterns bring on cool conditions and more precipitation, which tends to increase ice extent. However, individual cyclones may start to change the rules, putting more emphasis on ice break up as a factor in ice loss. Scientists don’t quite know yet if that is the case. Serreze warned, however, that at some point, the ice becomes so thin it doesn’t matter if there’s a storm or not. “It’s just going to melt anyhow,” he said.

Reference

Zhang, J., R. Lindsay, A. Schweiger, and M. Steele. 2013. The impact of an intense summer cyclone on 2012 Arctic sea ice retreat. Geophysical Research Letters 40: 720-726, doi:10.1002/grl50190.