By Jane Beitler

Scientists look at changes in the extent of Arctic sea ice at summer's end—the seasonal minimum—as an indicator of climate change. Since 1979, that low mark is averaging eleven percent lower each decade. Will that downward slide continue? Scientists think yes, so the next question is how fast: will it be at a steady rate, will it slow down, or will it speed up? In any one year, the Arctic´s sea ice cover can get a nudge from unusually warm or cool weather patterns. But could Arctic weather patterns also be getting nudged by the loss of sea ice? NSIDC scientists Mark Serreze and Andy Barrett, and colleague John Cassano took a closer look at this question.

Changes amplified

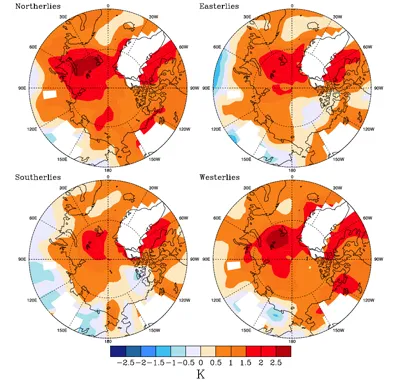

The loss of Arctic sea ice is not just a response to a warming planet—it also contributes to the warming. With less of the bright, white ice, more of the sun's energy is absorbed at the ocean surface in spring and summer, causing even more ice to melt. Scientists call this a feedback, and it is one of the ways that warming gets amplified in the Arctic. The sea ice cover is also influenced by weather patterns. Winds may push ice together and expose more open water. Warm winds from the south can promote more melt in summer, or less ice growth in winter. At other times weather patterns will slow summer melt, or foster more winter ice growth. What Serreze and colleagues are seeing is that temperatures associated with different Arctic weather patterns are starting to change, and that some of this change is itself due to the loss of sea ice.

Circulating the heat

The researchers compared temperature patterns for the period from 1979 to 2009 with the period from 2000 to 2009, to look for anomalies during this most recent decade of strong sea ice decline and Arctic warming. They then looked at how these temperature anomalies relate to changes in heat transfer from ocean surface to the air, changes in snow cover on land, and changes in the character of the winds. They found that while in general, winds from all directions now tend to be warmer they used to be, the warming in winter months is especially strong in areas that were formerly ice covered but are now free of ice, particularly in the Kara and Barents seas.

As winds blow over these open water areas, they pick up heat being released by the underlying ocean. This heat is then carried downwind to warm surrounding regions. However, they also found that part of the reason why there is less winter ice in the Kara and Barents seas regions in the first place is that warm winds from the south have also have become more frequent. Changing ocean currents have likely also played a role. This complex interplay of processes documents some of the challenges that scientists face in trying to predict both the pace of Arctic warming and the pace of sea ice decline.

References

Serreze, Mark C., Andrew P. Barrett, and John J. Cassano. 2011. Circulation and surface controls on the lower tropospheric air temperature field of the Arctic. Journal of Geophysical Research 116, D07104, doi:10.1029/2010JD015127.