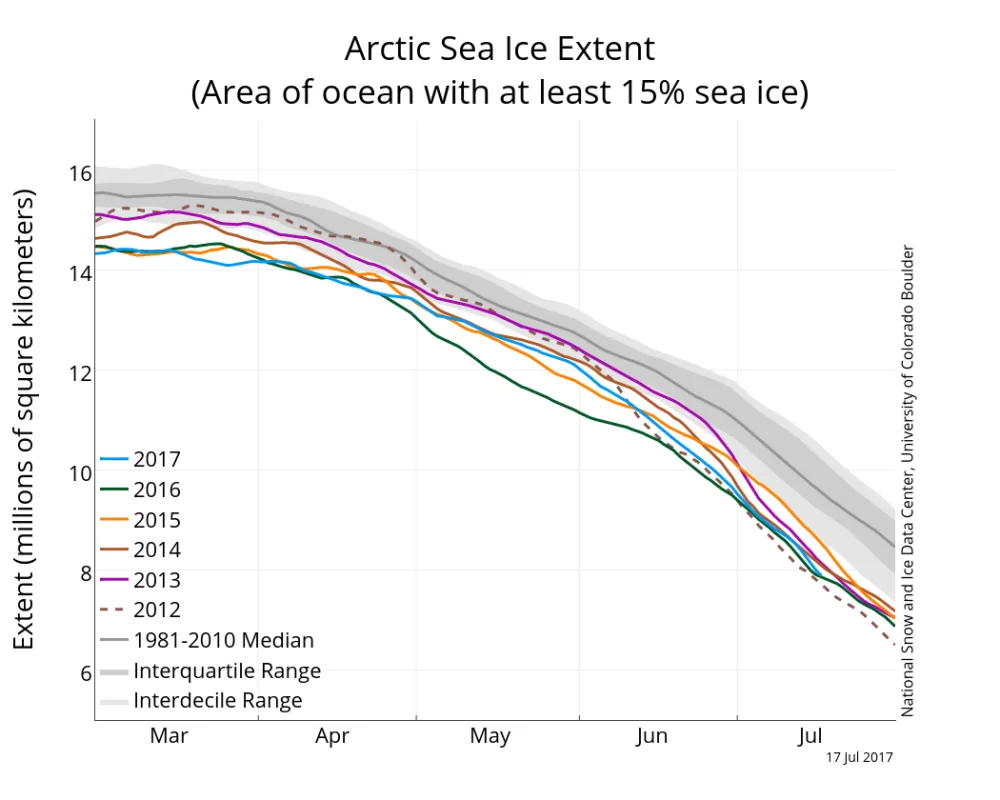

Arctic extent nearly matched 2012 values through the first week of July, but the rate of decline slowed during the second week. Weather patterns were unremarkable during the first half of July.

Overview of conditions

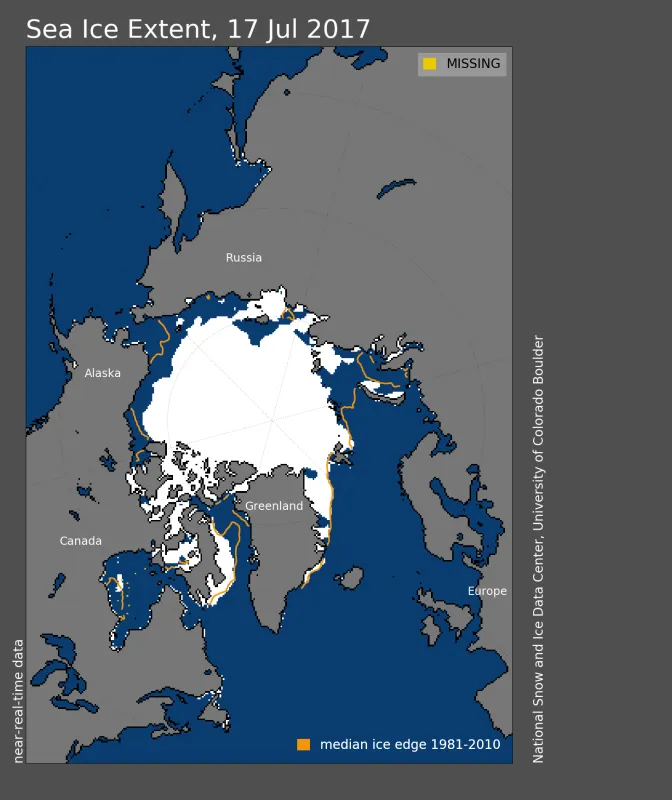

As of July 17, Arctic sea ice extent stood at 7.88 million square kilometers (3.04 million square miles). This is 1.69 million square kilometers (653,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average, and 714,000 square kilometers (276,000 million square miles) below the interdecile range. Extent was lower than average over most of the Arctic, except for the East Greenland Sea (Figure 1). Hudson Bay was nearly ice free by mid July, much earlier than is typical, but in line with what has been observed in recent years.

Conditions in context

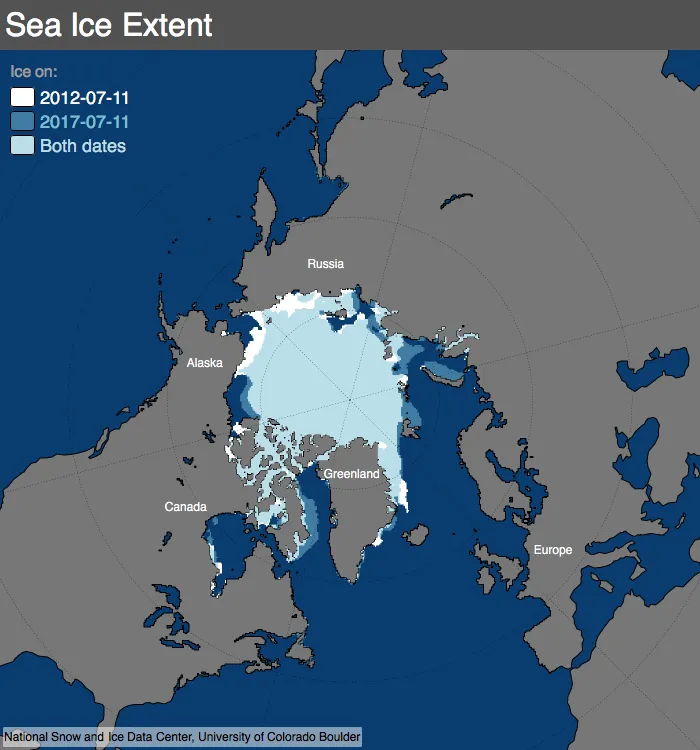

Through the first week of July, extent closely tracked 2012 levels. The rate of decline then slowed, so that as of July 17, extent was 169,000 square kilometers (65,300 square miles) above 2012 for the same date (Figure 2a). The spatial pattern of ice extent differs from 2012, with less ice in the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas in 2017, but more in the Beaufort, Kara, and Barents Seas and in Baffin Bay (Figure 2b).

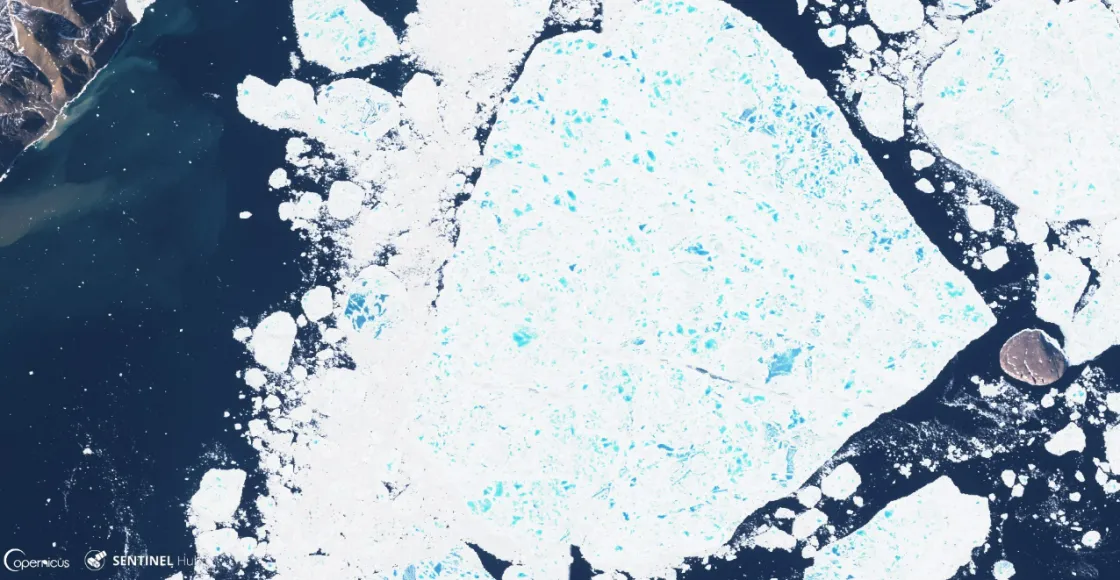

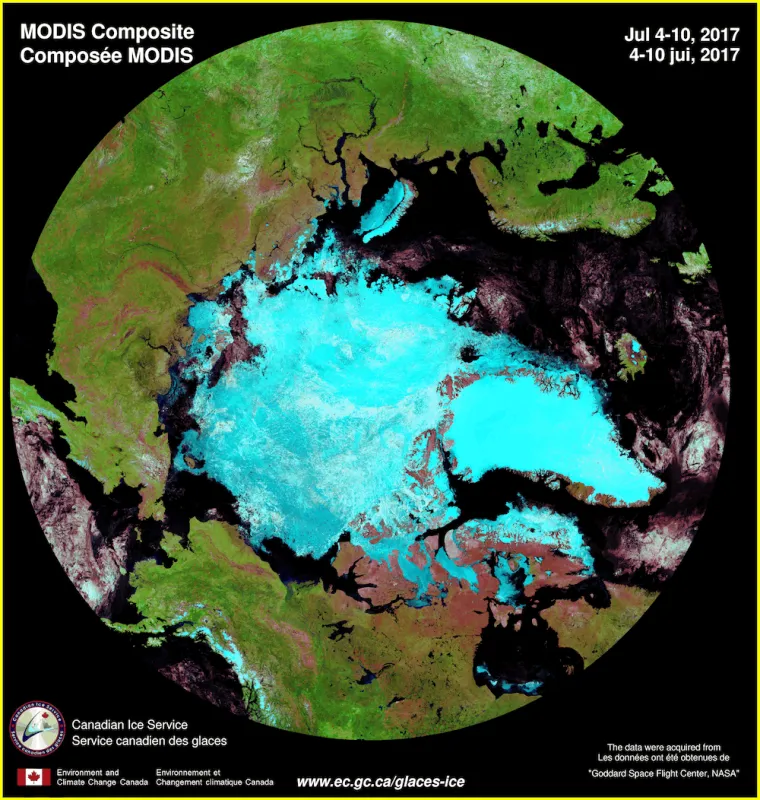

Visible imagery provides up close details

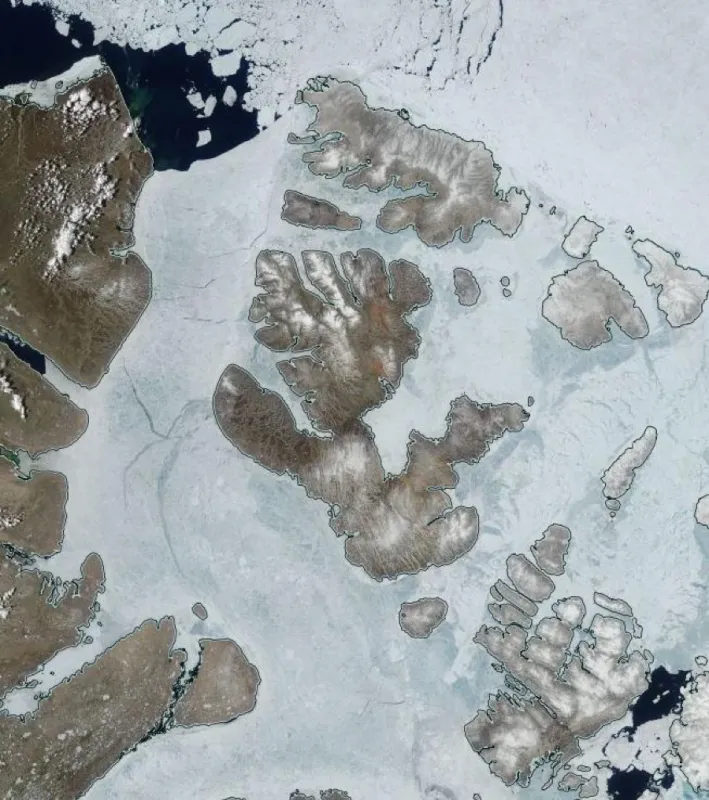

NSIDC primarily relies on passive microwave data because it provides complete coverage—night and day, and through clouds—and because it is consistent over its long data record. However, other types of satellite data, for example visible imagery from the NASA MODIS instrument on the Aqua and Terra satellites or from the European Space Agency Sentinel 2 satellite, can sometimes provide more detail. When skies clear, details of the ice cover can be seen, including leads, individual ice floes and melt ponds. For example, on July 3 in the Canadian Archipelago, 1-kilometer resolution MODIS imagery shows that the ice surface has a distinctive blueish hue due to the presence of melt ponds on the surface (Figure 3a). Higher resolution Sentinel-2 imagery (10 meters, Figure 3b) on the other hand provides up close detail on individual melt ponds on the ice floes.

The Arctic is a cloudy place, and generally, it is difficult to obtain a clear-sky image of the entire region. However, if images are compiled, or composited, over several days, most of the region may have at least some clear sky. This approach can yield a composite image that is mostly cloud-free. The Canadian Ice Service uses this approach to create a weekly nearly cloud-free composite image of the Arctic (Figure 3c). However, because the ice cover moves (typically several kilometers per day) and melts (during the summer), over the week-long composite period, fine details that can be seen in the daily imagery are not as evident because they have been “smeared” out over the week.

An ice-diminished Arctic

In response to diminishing ice extent, the US Navy has been holding a semi-annual symposium to bring together scientists, policy makers, and others to discuss the sea ice changes and their impacts. The seventh Symposium is taking place this week in Washington, DC, and will be attended by NSIDC scientists Mark Serreze, Walt Meier, Florence Fetterer, and Ted Scambos.

Tendency for warmer winters is increasing

A new study published this week in Geophysical Research Letters by Robert Graham at the Norwegian Polar Institute shows that warm winters in the Arctic are becoming more frequent and lasting for longer periods of time than they used to. Warm events were defined by when the air temperatures rose above -10 degrees Celsius (14 degrees Fahrenheit). While this is still well below the freezing point, it is 20 degrees Celsius (36 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than average. The last two winters have seen temperatures near the North Pole rising to 0 degrees Celsius. While an earlier study showed that winter 2015/2016 was the warmest recorded at that time, the winter of 2016/2017 was even warmer.

Reference

Graham, R. M., L. Cohen, A. A. Petty, L. N. Boisvert, A. Rinke, S. R. Hudson, M. Nicolaus, and M. A. Granskog. 2017. Increasing frequency and duration of Arctic winter warming events, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, doi:10.1002/2017GL073395.