While the Arctic summer is waning, sea ice extent continues to drop. In early August, ice-free pockets began to develop in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas and expanded steadily through the first half of the month.

Overview of conditions

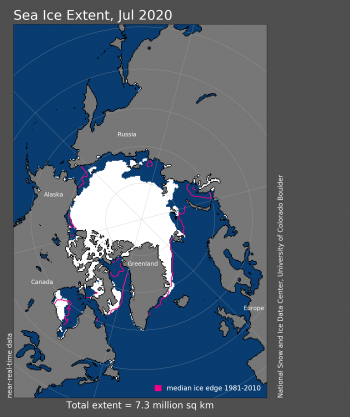

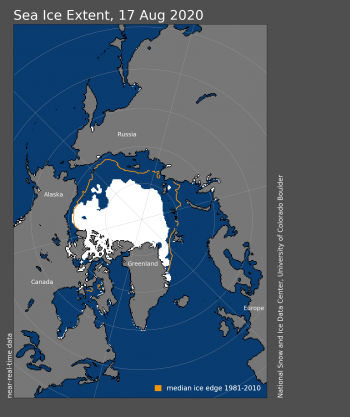

Figure 1a. Arctic sea ice extent for August 17, 2020 was 5.15 million square kilometers (1.99 million square miles). The orange line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that day. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

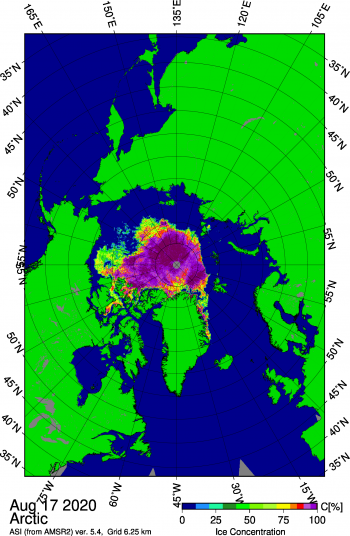

Figure 1b. This Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) image shows sea ice concentration in the Arctic Ocean on August 17, 2020, highlighting the openings of sea ice north of Alaska within the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

Credit: University of Bremen

High-resolution image

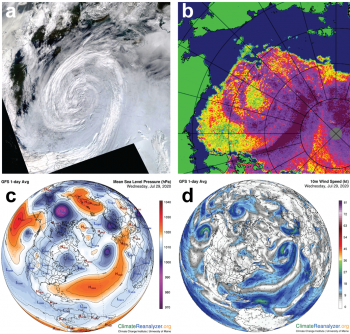

Sea ice extent stood at 5.15 million square kilometers (1.99 million square miles) on August 17, essentially tied with 2007 for the third lowest extent for the date since the satellite record began in 1979 (Figure 1a). The August 17 extent was lower only in 2012 and 2019. The most notable feature during the first half of August was the development of substantial openings of the sea ice north of Alaska within the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. This may be related to the mid-July storm that passed and spread out the ice cover, creating openings in the sea ice.

The reduced concentration patches and initial openings were first observed in higher-resolution Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) fields from the University of Bremen (Figure 1b). By the middle of the month, the ice-free areas had greatly expanded. Meanwhile, another open water patch developed north of the Mackenzie River delta. Persistent offshore winds have also moved the pack ice edge northward from the northern Greenland and Ellesmere coasts.

The Northern Sea Route has been open for a few weeks. The Northwest Passage appears to be mostly ice-free with a little ice remaining within Victoria Strait. The deeper Parry Channel still contains a substantial amount of sea ice and will likely not open this year.

Conditions in context

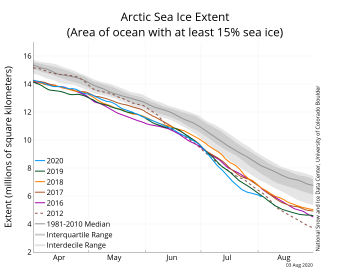

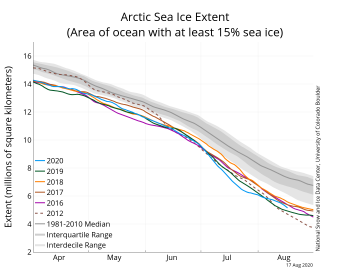

Figure 2a. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of August 17, 2020, along with daily ice extent data for four previous years and the record low year. 2020 is shown in blue, 2019 in green, 2018 in orange, 2017 in brown, 2016 in purple, and 2012 in dashed brown. The 1981 to 2010 median is in dark gray. The gray areas around the median line show the interquartile and interdecile ranges of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

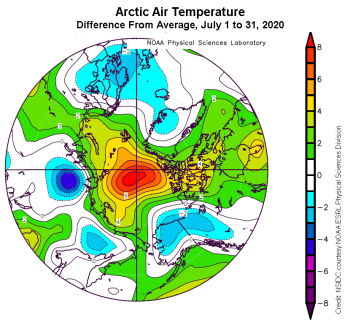

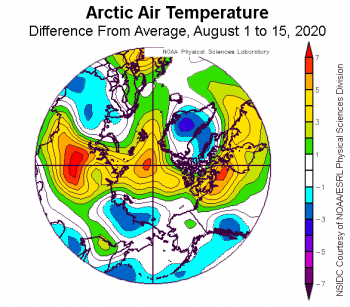

Figure 2b. This plot shows the departure from average air temperature in the Arctic at the 925 hPa level, in degrees Celsius, from August 1 to 15, 2020. Yellows and reds indicate higher than average temperatures; blues and purples indicate lower than average temperatures.

Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division

High-resolution image

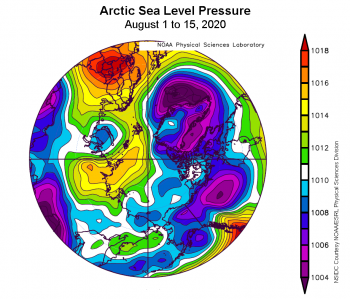

Figure 2c. This plot shows average sea level pressure in the Arctic in millibars (hPa) from August 1, 2020 to August 15, 2020. Yellows and reds indicate high air pressure; blues and purples indicate low pressure.

Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division

High-resolution image

From July 27 through August 8, 2020, extent declined 470,000 square kilometers (181,000 square miles), which is less than half of the average 1981 to 2020 extent loss of 950,000 square kilometers (367,000 square miles) during the same period (Figure 2a). After August 8, the rate of loss increased again due in part to melt in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, though the loss rate was still slower than average.

As assessed from August 1 to 15, air temperatures at the 925 mb level (about 2,500 feet above sea level) were above average over much of the Arctic Ocean, with air temperatures up to 7 degrees Celsius (13 degrees Fahrenheit) above average over the North Pole. Temperatures were 1 to 3 degrees Celsius (2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) below average in the East Siberian Sea region (Figure 2b). The atmospheric circulation was characterized by generally high pressure on the Eurasian side of the Arctic and low pressure on the North American side (Figure 2c).

2020 Arctic sea ice minimum forecasts

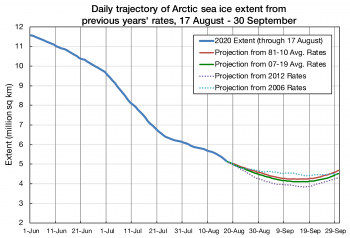

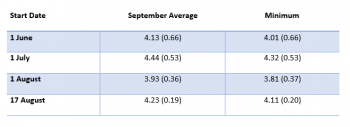

Figure 3. This figure show Arctic sea ice extent projections using data through August 17, 2020. These projections include the 2020 minimum and September 2020 average extent. These are based on the average loss rates for the years 2007 to 2019. The variation in the projection decreases for later dates because there is less time for variation before the end of the melt season.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

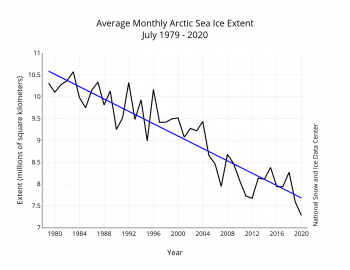

Table 1. This table shows a projection of Arctic sea ice extent for the September average and the daily minimum starting from June 1, July 1, August 1, and August 17, 2020. The projection is based on the average of the 2007 to 2019 estimates and the standard deviation range is in parentheses. Units are in millions of square kilometers.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

The end of the summer melt season, when the Arctic sea ice extent reaches its seasonal minimum, is likely about three to four weeks away. Over the last several years, there has been a community effort, called the Sea Ice Outlook, to submit seasonal projections of the September monthly average extent and the daily seasonal minimum. One submission by Arctic Sea Ice News & Analysis (ASINA) team member Walt Meier uses ice extent loss rates from previous years to project this year’s ice loss through the end of summer. Projections of the minimum and September average extent are submitted using data through the beginning of June, July, and August as starting points. Another projection with data through August 17 is included here to provide a further update (Figure 3 and Table 1). The projections are based on the average loss rates for the years 2007 to 2019. The variation in the projection decreases for later dates because there is less time before the end of the melt season. Note how the projections have seesawed up and down from June through mid-August. This is a result of the changes in the extent loss rates from one period to the next; it highlights how strongly weather conditions affect the ice loss through the summer, as well as the influence of thickness on how fast ice is melted away.

Another projection from National Snow and Ice Data Center scientist Andy Barrett, using a probabilistic method developed by our former colleague Drew Slater, projects a September average extent of 4.48 million square kilometers (1.73 million square miles), which is slightly higher than the Meier method prediction.

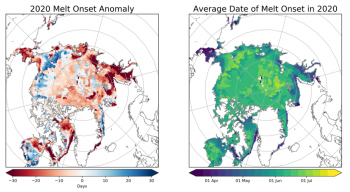

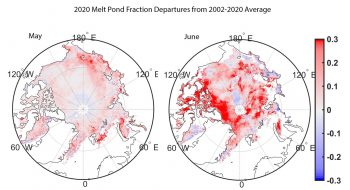

Past ice-free Arctic Oceans

Climate models are projecting that under continued warming trends, the Arctic Ocean may become substantially ice-free during the summer within the next 30 years. Such a state would be unprecedented for at least thousands of years. However, such conditions may have existed during the Last Interglacial (LIG) period, about 130,000 to 116,000 years before present, when summer Arctic air temperatures were 4 to 5 degrees Celsius (7 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. Previous model simulations were unable to capture the reconstruction of LIG Arctic temperatures, and a likely cause was a simplified treatment of sea ice that did not represent the influence of melt ponds on summer sea ice loss. The latest version of the UK Hadley Centre Global Environment Model version 3 (HadGEM3) climate model includes more complex characterization of melt ponds. In a recent paleoclimate study, this model was able to reproduce the reconstructed estimates of summer Arctic air temperatures during the LIG. This supports previous studies showing that melt pond formation is a key factor in the loss of summer sea ice because formation of melt ponds earlier in the season results in more absorption of solar energy through the summer and therefore more ice melt. ASINA team member Julienne Stroeve is a co-author on the study.

Farewell to the Milne Ice Shelf

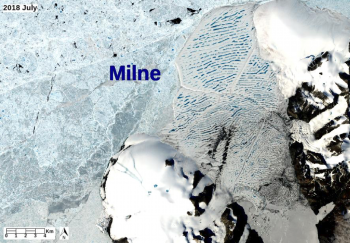

Figure 4. This NASA Landsat 8 true color image shows the former extent of the Milne Ice Shelf on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada, on July 23, 2018. It was acquired with off-nadir pointing of the satellite. The shelf is covered with linear blue lakes of meltwater that collect in the gently folded (corrugated) surface. In the upper left is the Arctic Ocean covered by perennial sea ice.

Credit: NASA

High-resolution image

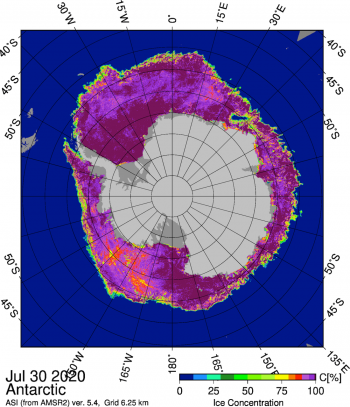

Another recent notable event in the Arctic was the calving of a large area of the Milne Ice Shelf off Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada, in late July. The Milne Ice Shelf had been Canada’s last intact Arctic ice shelf. A piece of the shelf measuring about 81 square kilometers (31 square miles), which made up about 43 percent of the total ice shelf area, broke off on July 30 and 31. Warm air temperatures and offshore winds likely triggered the ice shelf collapse. Offshore winds move the perennial sea ice cover north from the coast, reducing the compressive forces that hold the shelf in, and potentially contribute to basal melting of the ice by allowing solar energy to warm the upper ocean layer. Polar explorer Robert Peary discovered the Canadian Arctic ice shelves, once a single 9,000-square kilometer (3,475-square mile) sheet, in 1902. Although evidence from seal remains and driftwood suggests they were thousands of years old, they have dwindled dramatically and now comprise of only a few small ice-covered fragments in inlets along the northernmost coast of Canada.

Rest in peace, Koni Steffen

Former Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences director Konrad Steffen passed away on August 8, 2020, while conducting field work on the Greenland Ice Sheet. He will be missed. Photo courtesy of CIRES/CU Boulder.

As has been widely reported, the polar climate community suffered a huge loss in the tragic death of our colleague and former Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences director, Konrad (Koni) Steffen on the Greenland Ice Sheet. He was an outstanding researcher, science communicator, and friend. He is most remembered for his research on the Greenland Ice Sheet, including an invaluable 30-plus-year climate record of station data spanning the island that he instituted and maintained. Earlier in his career, he conducted substantial research on sea ice, visiting both polar regions. Early papers of his (e.g., Steffen and Schweiger, 1991; Steffen et al., 1992) helped provide key validation of the sea ice concentration and extent products that we employ in our analyses here. He will be missed.

Further reading

Guarino, M., L. C. Sime, D. Schröeder, et al. Sea-ice-free Arctic during the Last Interglacial supports fast future loss. Nature Climate Change. (2020). doi.10.1038/s41558-020-0865-2.

Steffen, K., J. Key, D. J. Cavalieri, J. Comiso, P. Gloersen, K. St. Germain, and I. Rubinstein. 1992. The estimation of geophysical parameters using passive microwave algorithms. American Geophysical Monograph Series. doi:10.1029/GM068p0201.

Steffen, K., and A. Schweiger. 1991. NASA team algorithm for sea ice concentration retrieval from Defense Meteorological Satellite Program special sensor microwave imager: comparison with Landsat satellite data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. doi:10.1029/91JC02334.