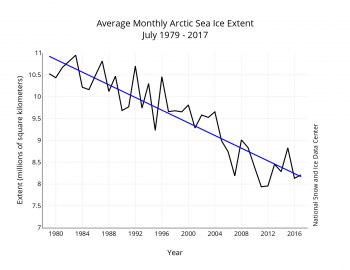

A cooler than average first half of the month kept ice loss at a sluggish pace with little change in the ice edge within the eastern Arctic. Retreat was mostly confined to the western Beaufort and northern Chukchi seas. Ice extent remains above that seen in 2012 and 2007.

Overview of conditions

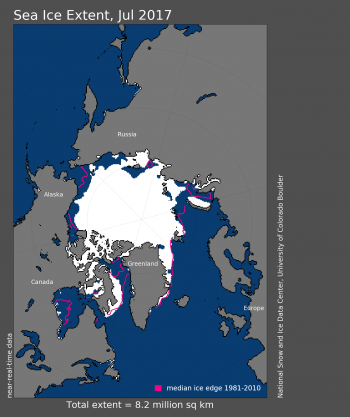

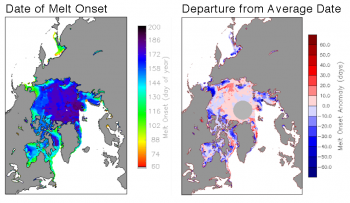

Figure 1. Arctic sea ice extent for August 21, 2017 was 5.27 million square kilometers (2.03 million square miles). The orange line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that day. Sea Ice Index data. About the data

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

On August 21, 2017, ice extent stood at 5.27 million square kilometers (2.03 million square miles). This was 1.82 million square kilometers (703,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 median extent for the same day, and 804,000 square kilometers (310,000 square miles) and 221,000 square kilometers (85,000 square miles) above the 2012 and 2007 extents for the same day, respectively. The ice edge remained nearly constant through the first half of the month in the Barents and Kara Seas, and retreated only slightly within the East Greenland Sea. The ice edge also remained stable in the Laptev and East Siberian Seas through the first half of the month. Ice retreat occurred primarily within the Chukchi and western Beaufort Seas as well as near the New Siberian Islands. Some ice continues to block the Northern Sea Route near Severnaya Zemlya. Both McClure Strait and the Amundsen Gulf routes within the Northwest Passage remain blocked by ice. On August 17, the Russian nuclear powered icebreaker 50 let pobedy reached the North Pole in just 79 hours, the fastest time yet.

Conditions in context

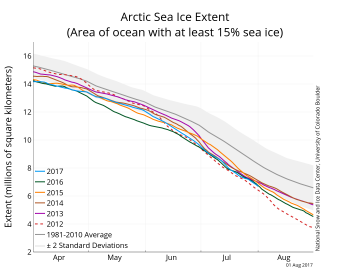

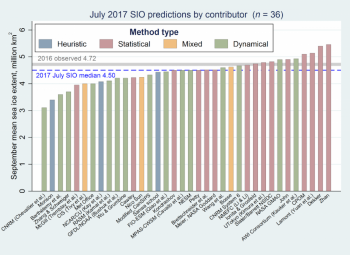

Figure 2. The graph above shows Arctic sea ice extent as of August 21, 2017, along with daily ice extent data for five previous years. 2017 is shown in blue, 2016 in green, 2015 in orange, 2014 in brown, 2013 in purple, and 2012 as a dashed line. The 1981 to 2010 median is in dark gray. The gray areas around the median line show the interquartile and interdecile ranges of the data. Sea Ice Index data.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Ice retreat from August 1 to August 21 averaged 73,000 square kilometers (28,000 square miles) per day. This was faster than the 1981 to 2010 average rates of ice loss of 57,300 square kilometers (22,000 square miles) per day, but slower than in 2012, which exhibited the fastest rate of ice loss compared to any other August in the passive microwave satellite data record. Normally the rate of ice retreat slows in August as the sun starts to dip lower in the sky. The rate of ice loss was more rapid at the beginning of August, slowing down considerably starting on August 17.

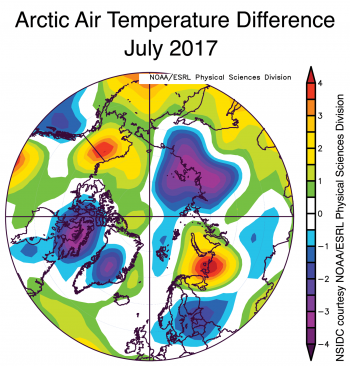

Air temperatures the first two weeks of August were 1 to 3 degrees Celsius (2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than the 1981 to 2010 average throughout the Arctic Ocean and over Greenland and the North Atlantic. The lowest air temperatures relative to the long-term average were found in coastal regions of the Kara and Barents Seas, continuing the pattern seen throughout much of this summer. Cooler than average conditions within the Central Arctic were a result of persistent cold-core cyclones. These cyclones have not been as large or as strong as the Great Arctic Cyclones of 2012 and 2016, despite the central pressure of one of these systems dropping down to 974 hPa on August 10. In addition, these cyclones are located closer towards the pole within the consolidated ice pack, where they are less likely to cause significant ice loss, as did the 2012 Great Arctic Cyclone in the Chukchi Sea.

While air temperatures start to drop in August, ice melt continues through the month as heat gained in the ocean mixed layer during summer continues to melt the ice from below and from the sides. Sea surface temperatures have been up to 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) above average near the coastal regions, but generally near average or slightly below average along the ice edge in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

NASA Operation IceBridge conducts summer flights

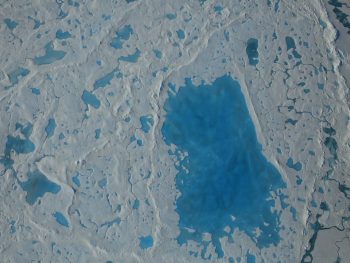

Figure 3. This photograph, taken during NASA Operation IceBridge on July 25, 2017, shows melt ponds on the surface of Arctic sea ice.

Credit: Eric Fraim/NASA

High-resolution image

NASA’s Operation IceBridge (OIB) airborne campaign flew several missions over the Greenland ice sheet this summer to study changes in Greenland outlet glaciers, as well as to observe sea ice. A recent mission collected laser altimeter data to investigate sea ice thickness changes resulting from the piling up of sea ice (or convergence) as ice motion pushes the ice up against the coast. Flights were completed on July 17 and July 25. High-resolution visible imagery collected on the flights also provides close-up looks of melt pond development.

Influence of warm Pacific water

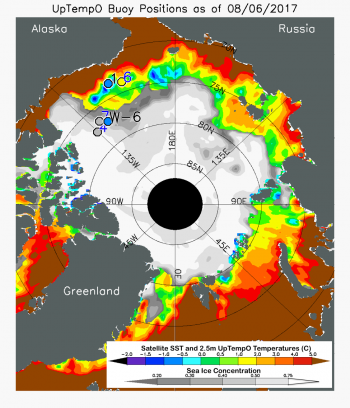

Figure 4. This plot shows measurements of sea surface temperature from drifting buoys, along with satellite-derived sea surface temperature from NOAA and ice concentration from NSIDC for August 6, 2017. Buoy positions as of August 6 are indicated with circles. A gray dot indicates that the buoy is reporting a temperature value outside the range of -2 to 10 degrees Celsius. Red, orange, and yellow indicate higher temperatures, while blues and purples indicate lower temperatures. Whites indicate higher sea ice concentration, and grays indicate lower concentration.

Credit: University of Washington Polar Science Center

High-resolution image

This May, sea ice in the Chukchi Sea was at a record low for the satellite data record. The early retreat of ice in this region may partially be a result of unusually warm ocean temperatures in the region. As reported by Rebecca Woodgate of the University of Washington, Seattle, the Research Vessel Norseman II spent eight days in the Bering Strait and southern Chukchi Sea region to recover oceanographic moorings and whale acoustic instruments, in addition to deploying new instruments. The mooring data indicated early arrival of warm water in the strait, about a month earlier than the average, resulting in June ocean temperatures that were 3 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) above average. Early intrusion of warm water in the Bering Strait back in May helped to melt sea ice from below, and may have been one of the factors for early development of open water in the region.

Arctic air temperatures and the Paris Climate Accord target

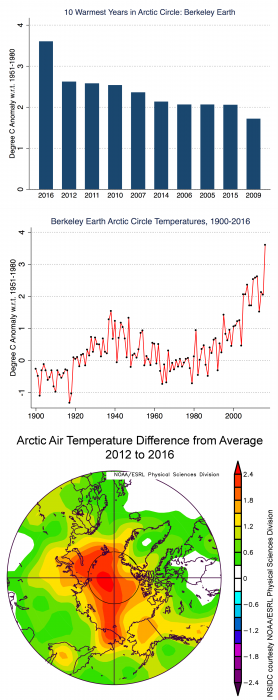

Figure 5. The bar graph, top, shows the Berkeley Earth evaluation of the ten warmest years since 1979 in the Arctic north of 80°N; the plot, middle, shows Arctic average temperatures for the period 1900 to 2016, relative to a 1951 to 1980 reference period; bottom, a map of Arctic temperature differences, in degrees Celsius, for the 2012 to 2016 period (5 years) relative to a 1981 to 2010 reference period.

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

High-resolution image

Our past reports, and many other sources, have noted that the Arctic region is warming faster than the rest of the globe. This warming has accelerated in recent years, particularly since 2005. The ten warmest years on record for the Arctic are within the past twelve years, and 2016 was by far the warmest in the record since 1900. These observations are supported by both NOAA National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) reanalysis climate data, and by our colleagues at Berkeley Earth. Berkeley Earth is an independent climate fact- and analysis-checking group dedicated to an objective evaluation of the main claims and data sets used to support climate trends and forecasts.

One of the major statements of the recent Paris Climate Accord, dealing with heat-trapping ga reductions, is a target to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above the pre-industrial average. While this reference for the increase (pre-industrial average) is somewhat ambiguous, using reference average temperatures of either 1951 to 1980 or 1980 to 2010 for the Arctic shows that much of the area north of 80°N is already above this guideline over the past five years (2012 to 2016). As the Arctic will likely continue to warm above 2 degrees Celsius, other areas will need to warm less than that if the threshold is not to be exceeded. In general, land warms about 30 percent faster than oceans in the models, so in a global-average 2 degree Celsius warmer world, much of the global land area would have warmed more than 2 degrees Celsius.

The annual average air temperature for 2016 for the Arctic north of 80°N was more than 3.5 degrees Celsius (6.3 degrees Fahrenheit) above the 1951 to 1980 reference period, the warmest year yet, and most years during the past decade had annual average temperatures between 2 to 2.5 degrees Celsius (3.6 to 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit) above the reference period. Geographically, the NOAA NCEP reanalysis shows that recent warming is primarily located over the Arctic Ocean, and smaller warming trends are seen in the circum-Arctic land areas.

Further reading

Hawkins, E., Ortega, P., Suckling, E., Schurer, A., Hegerl, G., Jones, P., Joshi, M., Osborn, T.J., Masson-Delmotte, V., Mignot, J. and Thorne, P. 2017. Estimating changes in global temperature since the pre-industrial period. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0007.1.